By Jeff Reardon

Last week, Maine’s Legislature overrode a veto by Governor Paul Lepage with an overwhelming bipartisan vote—35-0 in the Republican-controlled Senate; 122-21 in the Democratically-controlled House—to finally pass a bill that gives Maine protective rules for metallic mineral mining.

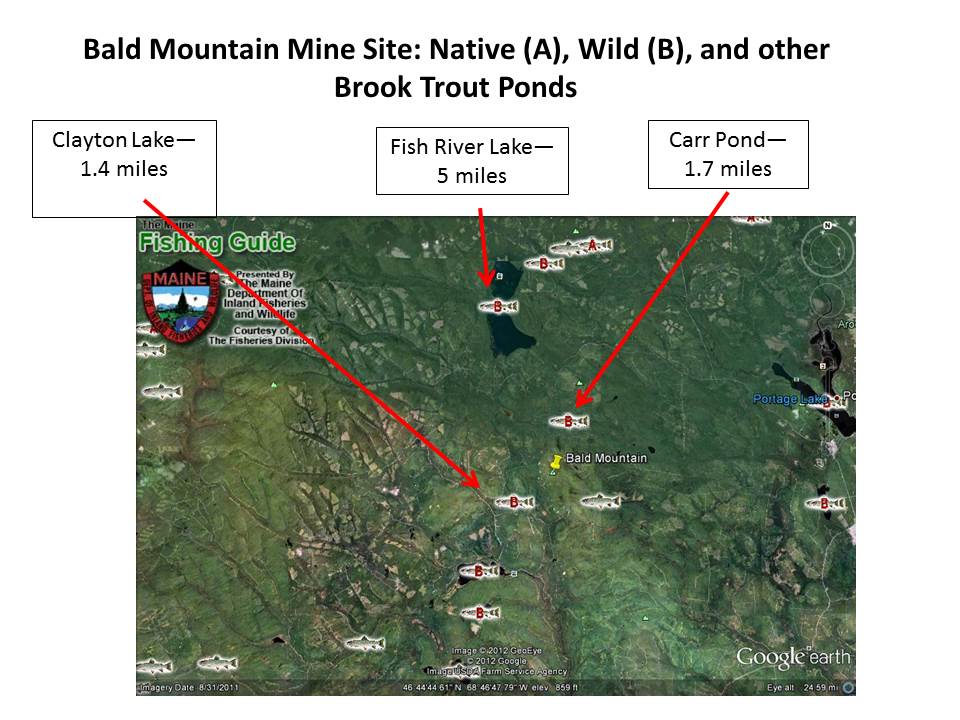

That decision ended more than five years of work by Trout Unlimited and other Maine environmentalists that began in 2012, when the Legislature, in a close vote, passed a bill that literally erased Maine’s framework of law and rules to govern Metallic Mineral Mining, and replaced it with a new framework specifically designed to facilitate a large open pit copper and gold mine at the headwaters of the Fish River and the Aroostook River, two of northern Maine’s best wild trout watersheds. We lost the initial battle, badly, in 2012.

But we put up a hell of a fight, with help from all over TU’s growing family of staff and volunteers, and by working closely with a variety of partners.

Chris Hunt, then our National Director of Communications, helped me draft an Op Ed for the Bangor Daily News about what industrial-scale sulfide mining might do to Maine brook trout on about 20 minutes notice when we heard about the 2012 bill. Steve Moyer, vice president for government affairs, hooked us up with our good friends at Earth Works so I’d know something about mining when I testified at the hearing on the bill, for which we had less than 2 days to prepare. Amy Wolfe, Director of TU’s Eastern Abandoned Mine Program, dropped everything and sent me some devastating statistics, maps and graphics about acid mine drainage and its impacts on the West Branch Susquehanna, along some juicy photos of AMD dripping into Kettle Creek.

Bruce Farling from the Montana State Council of TU kicked in some horror stories from the Clark Fork in Montana and some four-lettered encouragement. Suitably armed, I testified in opposition to a bill designed to facilitate a huge open pit mine — and found some company with other groups who shared our concerns.

An ad-hoc coalition quickly formed with Maine Audubon (our long-term partner on the Maine Brook Trout Survey project), the Natural Resources Council of Maine, and a variety of other environmental groups. We worked with Maine Conservation Voters to make the mining bill a “Defensive Priority ”— and the issue has been a priority on that group’s annual Conservation Agenda ever since.

With our friends from the Natural Resources Council of Maine, we trekked up to Presque Isle on the Fish River and talked to local activists about brook trout and acid mine drainage. They started trekking down to Augusta to testify at hearings — a five hour one-way drive. Former Maine Council Chair Greg Ponte got volunteers to staff a booth every year at the Presque Isle Fish and Game Show to do two things — recruit a kid or two from Aroostook County to Trout Camp, and talk mining and brook trout.

Council Chair Kathy Scott let me turn Maine Council meetings into mining hearing organizing events. TU member Tom Whittle, who retired to Maine after a long career in Pennsylvania, testified about how his TU Chapter there shoveled 99 tons of crushed limestone a year into a doser on a tributary to Stony Creek so it could continue to support wild trout.

We worked with some key legislative partners to force a more considered review, and public hearing with good notice at which more than a hundred Maine citizens, including more than a dozen TU members, testified about the dangers of mining.

But we still got our asses handed to us and lost the vote.

Fortunately, the new law required rulemaking by Maine’s Board of Environmental Protection, and those rules had to be approved by both houses of the Maine Legislature.

From early 2013 until last December, we fought through three rounds of that rulemaking process. Three times the Board of Environmental Protection proposed rules that were not protective. Three times TU and a growing number of citizen activists stood up and said so, and told the Board that we didn’t think it would be possible to write protective rules because they were based on a lousy piece of law.

We talked about brook trout, how Maine had the lion’s share of remaining intact brook trout habitat, about what mining had done to Pennsylvania brook trout and Montana cutthroats and BC steelhead.

Three times, the Board approved bad rules and sent them on to the Legislature, and twice, a loud chorus of Maine citizens got the Maine Legislature riled up to reject the rules.

While this was going on, the Mt. Polley tailings dam failure devastated Quesnel Lake in British Columbia. Then the wastewater plume from the Gold King mine turned the Animas River orange. And the Samarco tailings dam let go in Brazil and flowed all the way to the Atlantic Ocean, killing 17 people.

The Maine Environmental Priorities Coalition made mining bills priorities year after year. Finally, in January 2017, the Board of Environmental Protection listened closely to what we’d all been saying. It helped that in response to their draft rule, they got comments from 441 individuals from 188 Maine towns opposing the rules — balanced by two comments supporting them.

Irving, the Canadian forestry, mining and oil company who drove the 2012 law, disappeared. George Smith, the former Executive Director of the Sportsmen’s Alliance of Maine, and now a columnist and blogger for several local newspapers, wrote columns about how Maine brook trout were more valuable than gold.

The Board still approved rules that were too weak, but when they sent them on to the Legislature, they attached a cover letter that said they would have liked to make them better, but the law didn’t let them. So they asked for the law to be made stronger in four specific ways.

We worked with partners at Maine Conservation Voters, NRCM, and Maine Audubon — with Nick Bennett from NRCM doing the heavy lifting, and me, Beth Ahearn from Maine Conservation Voters, and Jenn Gray from Maine Audubon twisting his arm to make him do it even though it was a waste of time — to draft a bill, sponsored by Senator Brownie Carson, the former head of NRCM, that incorporated those suggestions. We didn’t really think it had much chance of passing, but we wanted a vehicle to talk about responsible mining as a counterweight for our push to — again — defeat a bad set of rules so we could maintain the stalemate.

And suddenly the wind shifted and we pretty much got blown over.

We had Republican legislators — one of them a former Chair of the Maine BEP who had voted for an earlier and weaker version of the rules — competing to offer amendments to make the bill stronger. The Senate Chair of the Environment and Natural Resource Committee, who had led the Committee in approving the horrible 2012 law, got mad at us because we were working with Senator Carson on a “good mining” bill instead of doing it with him.

How about we ban open pit mines? Tailings impoundments? Maybe we need to rewrite this so it requires dry stacking of mine tailings? Is there way to make the groundwater protection language stronger? Can we be more specific about the financial assurance requirements? How about we require them to put up cash, up front — after evaluating a “worst case failure or disaster” and calculating the costs to clean it up?

The end result was passed out of Committee with a 12-1 “ought to pass” endorsement. (The lone dissenter would prefer to just ban mining, and is really mad at us for not finding a way to make that happen.) The bill then went to the Senate, where it passed 34-0, and the House, where it passed by 126-14. With a few changes around the edges, those votes held up after the Governor vetoed the bill.

The result is a mining law that:

•Bans open pit mines.

•Bans tailings impoundments

•Requires dry stacking of tailings.

•Bans “wet mine waste management units” (subaqueous deposition of mining waste to prevent AMD).

•Bans mining “in, on, or under” all state-owned lands, which in Maine includes subtidal wetlands and the land under lakes and ponds.

•Bans mining under “significant river segments”.

•Prevents any placement of mine waste or other potentially dangerous materials or operations in flood plains.

•Requires evaluation of a “worst case” failure based before approval of any mining applications, and that the applicant post financia assurances sufficient to clean up and remediate damage that might occur.

Many thanks to everyone in the TU family who helped me learn enough about mining back in 2012 to make some of the right noises, to the Maine grassroots members who rewrote testimony for hearing after hearing after hearing and showed up every time, like Bill Murray in Groundhog Day, and to our many partners who worked as hard as we did to pull this off. (Nick Bennett worked harder.)

Thanks also to brook trout for being so damn pretty and easy to organize around, and to Maine people who like brook trout as much as lobster, if such a thing is possible.

If anyone had asked me on New Year’s Day if there was a chance we’d be worried about how to pass a good mining bill in May, I would have said “Hell, no. If we’re lucky, we’ll beat the rules and we can do this all over again in 2019. I just hope we get that done before the Hendricksons start hatching in June.”

As it turned out, I was on my annual Baxter State Park remote pond vacation when the veto came down. I was casting dry flies to brook trout feeding on mayflies the afternoon of the vote, on a pond that is blissfully untouched by cell or wifi access. I didn’t hear the news until I came out of the woods and turned on Maine Public Radio in the truck. I can’t imagine a better time and place to have gotten the news.

Jeff Reardon oversees Trout Unlimited’s program in Maine. He’s an avid angler who recently battled horrendous mosquitos and black flies while chasing wild brookies during his annual trip to Baxter State Park.