Brook trout in the Northeast have taken a beating over the decades. Scientists estimate that brook trout—indicators of clean water and healthy lands—have lost more than half of their historic habitat to development, dams and urbanization. The brook trout of southeastern Massachusetts are particularly vulnerable, and worthy of protection.

There, a unique form of sea run brook trout, called “salters,” persists. The late Massachusetts statesman, Daniel Webster, is said to have caught a 14-pound salter in the 1800s.

On April 10, the people of Wareham, Mass., will decide whether 700 acres of a 1,000-acre pine barren in the headwaters of a stream called Red Brook can be converted into a development of hotels, multi-family homes and possibly a horse track and casino. Red Brook flows through the towns of Plymouth, Wareham and Bourne before emptying into the saltwater of Buttermilk Bay.

Red Brook is one of a handful of sea-run brook trout streams that remain south of Maine. The forest that would be razed, allows rainwater to slowly filter into the ground—providing the flows for Red Brook and the drinking water for the town.

I am an unabashed fan of salter brook trout. You consider yourself a seasoned, and somewhat knowledgeable, angler, only to learn of these furtive coastal fish that occupy both fresh and saltwater habitat and can grow four inches in a single winter in the saltwater. Salters move between freshwater and salt in response to weather, drought and other stressors. I have always thought of sea run brook trout as America’s fish—not simply, because they were one of the first and most prolific sport fish in our history. Salters demonstrate the type of resiliency and stick-to-it-iveness that make America great.

Somehow, sea run brook trout managed to survive the dam building frenzy of the 1800s and early 1900s in the northeast that has so imperiled Atlantic salmon. They clung to existence when their rivers were transformed into cranberry bogs. They persisted despite factories spewing pollution and toxins directly into streams before passage of the Clean Water Act.

And, for 30 years, Red Brook was the Salter equivalent of John Winthrop’s city upon a hill, demonstrating that despite the loss, despite the odds, that people and communities such as Wareham can work together to protect and recover rivers and keep these remarkable creatures from blinking out of existence.

Conservation efforts on Red Brook date to the 1980s when Trout Unlimited and other organizations worked with the Lyman family to protect the stream that flows through 650 acres. The proposed development would squat directly on top of the headwaters of Red Brook’s aquifer and the drinking water supply for the town’s drinking water wells.

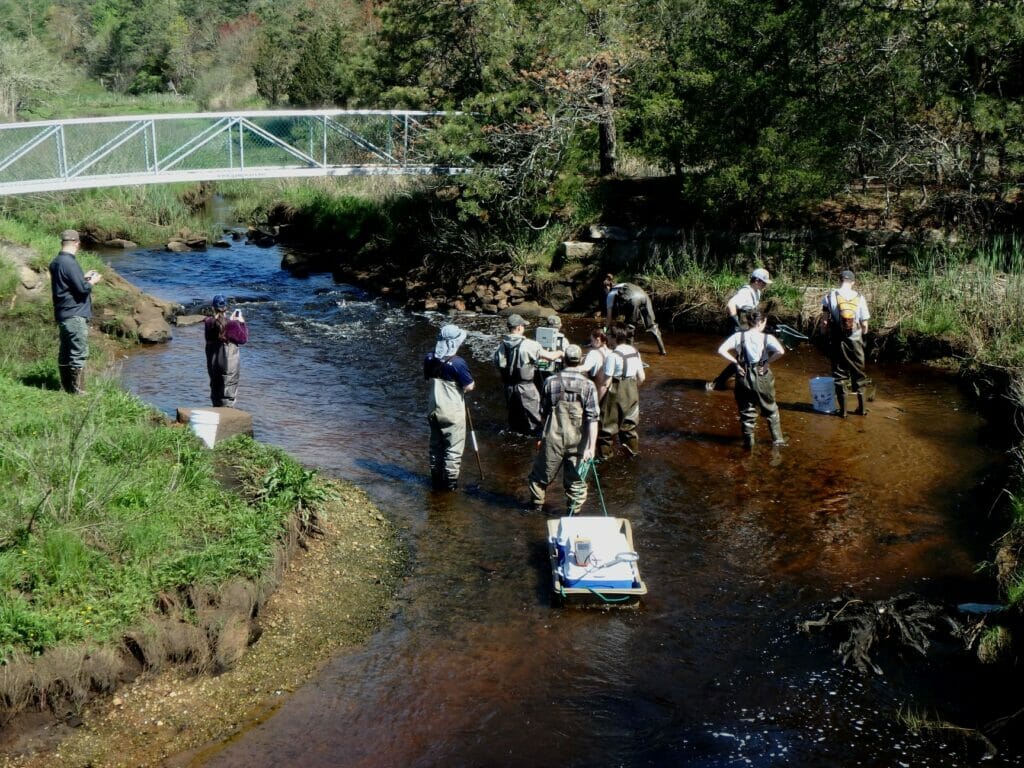

After 30 years of dam removals, tree plantings and other restoration work by TU and its partners, especially the Massachusetts Department of Fish and Wildlife, we have witnessed a seven-fold increase in the number of Red Brook salters.

The Trustees of Reservations and TU have spent more than $4 million to recover Red Brook over the years. Tens of thousands of volunteer hours have been donated to replant the streamside area and recover habitat. All of that could be lost on April 10, if the people of Wareham vote to allow the development and its potential run-off, sedimentation, nutrients and groundwater pollution to occur.

And, for 30 years, Red Brook was the salter equivalent of John Winthrop’s city upon a hill, demonstrating that despite the loss, despite the odds that people and communities such as Wareham can work together to protect and recover rivers and keep these remarkable creatures from blinking out of existence.

Most of the sea run brook trout have disappeared from Long Island—where Webster is said to have caught his behemoth—to southeast, Massachusetts. Six years ago, and 25 miles away from Wareham, the people of Mashpee awoke one fall morning after the state surveyed the Santuit River and found that one of the last Salter streams had died due to development and groundwater depletion. At the time, longtime salter advocate, Warren Winders, said, “While our backs were turned, the Santuit River quietly died.”

Few will likely mourn the loss of Red Brook and its salter brook trout. We have lost so much of our nation’s natural heritage. What is it to lose one more unique population of salters? The Boston Globe will not cover the story. It will not make the morning news on WBUR or Fox News.

If the people of Wareham vote “no,” others will take notice. It was the people of Wareham and their surrounding communities whose wisdom, work and good will led to the restoration and recovery of Red Brook in the first place. The people of Wareham can send a powerful message to communities across New England by voting “no” on April 10, and demonstrating that we are not a desperate nation willing to fill in every open space with concrete, glass and metal.

Please make a donation and support our local efforts to help the people of Wareham make the choice to protect “America’s fish” and not allow Red Brook to be ruined by yet another development. Big box developments such as the one proposed in the headwaters of Red Brook are as common as bird poop on a summer windshield. Salter streams are disappearing fast, but the story of Red Brook shows we can reverse that trend and recover America’s fish.

Chris Wood is the president and CEO of Trout Unlimited.