To celebrate Public Lands Month, many TU staffers took to their local public lands and waters to participate in #ResponsibleRecreation. Staying close to home while still getting out to enjoy the outdoors has been imperative for many during the pandemic. Here are some of their stories:

Exploring public land heritage along the Columbia River

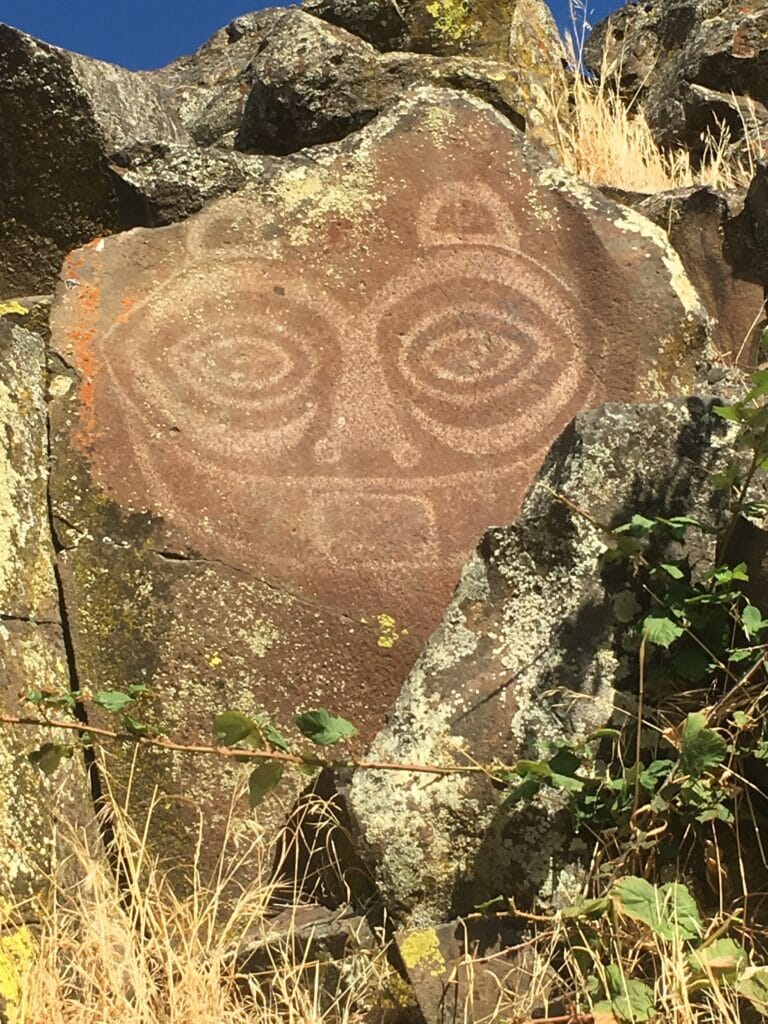

Tsagaglalal.

Tsagaglalal or “She who watches” in the Wasco-Wishram language, is a magnificent Tamani Pesh-Wa petroglyph, and she is literally less than 10 miles from my house. Sadly, I had not known of her existence until being relegated to my home during the pandemic.

The legend of Tsagaglalal tells of an indigenous female chief who was concerned over what would happen to her people when she was gone. Coyote came to her and told her that the world would change and that women would no longer be chiefs. Coyote then tricked her and turned her into a rock, saying, “Now you shall stay here forever, watching over your people and the river.”

As a high-risk family living in a rural community with limited healthcare options, we have been staying close to home, spending much of our free time completing housework and yard projects. Luckily, our community has a lot of public lands within a 30-minute drive for needed breaks from the acre we call home.

We are avid public lands enthusiasts, often overlooking our nearby lands to recreate as well as hunt, fish and harvest from public lands across the West. When we decided to stay close to home to protect ourselves and our community, we found ourselves seeing our “local” public lands in a new, unintended light.

Feeling confined in the backyard and ever curious, I started researching local public lands more deeply. I stumbled upon this indigenous land map which piqued my interest. I wanted to learn more. I started looking up every place I visited, which during the pandemic was frankly only public lands close to home. And then furthering that research, oftentimes down very enlightening rabbit trails, upon return to our home.

This is how I met Tsagaglalal. From learning about her existence, I dove into a learning journey about her people which led to a greater understanding and interest in the lost tribes of the Columbia River, the impact of Columbia River dams on indigenous culture and current land management. I’ve also started to learn more about tribal legacy in my own town. The impacts of which I see in my own community and resonate differently now as I wave to indigenous neighbors.

I’m now in the habit of researching the ancestral lands of where we intend to recreate to better understand the history of the land and the livelihoods of those who came before us and those who are still here. While this research answers questions I didn’t know I had, it also poses new questions about the lands and their management.

I’m still amazed and elated that a simple land acknowledgement opened my eyes to learning more about the deep history of our public lands. While this might look like 5 minutes of research en route to a new trailhead, it is 5 minutes that opens my eyes to experiencing the land in a new way. A new perspective.

— Lisa Beranek, leadership development manager

Moose and trout in Wyoming’s Bighorn country

Fishing on the North Tongue River (two days after a big snowstorm in Wyoming) wasn’t very fruitful but sure was fun. Plenty of trout swim these waters, including Yellowstone cutthroats, but this is a popular place and I suspect the fish were just tired. I’m not the most technical angler, but I had a few bites and a lot of giggles.

There were plenty of moose, though. I and the friend I was with saw six in just three days including a young bull calf. He popped out from the willows and I could hear his mama close by. Time to move to the next hole.

We also explored the headwaters of the Little Bighorn River, where the local TU chapter out of Sheridan had a sign explaining the benefits of cleaning fishing gear to reduce nonnative species invasion. This area and its beautiful small creeks was a surprise to us. We popped out of the forest into this small meadow, but with no fly rod in hand, we watched hoppers flop onto the surface and the small brookies and Yellowstone cutthroat trout lunge for this large meal.

All in all, this was my new discovery of some great public lands in my backyard (four hours away). I can see it’s a popular place with folks for fishing and hunting (bow season just opened and there were plenty of hunters around) yet the area was in good shape for the most part.

— Cathy Purves, foundation research and grants manager

It pays to visit public lands near home along Colorado’s Front Range

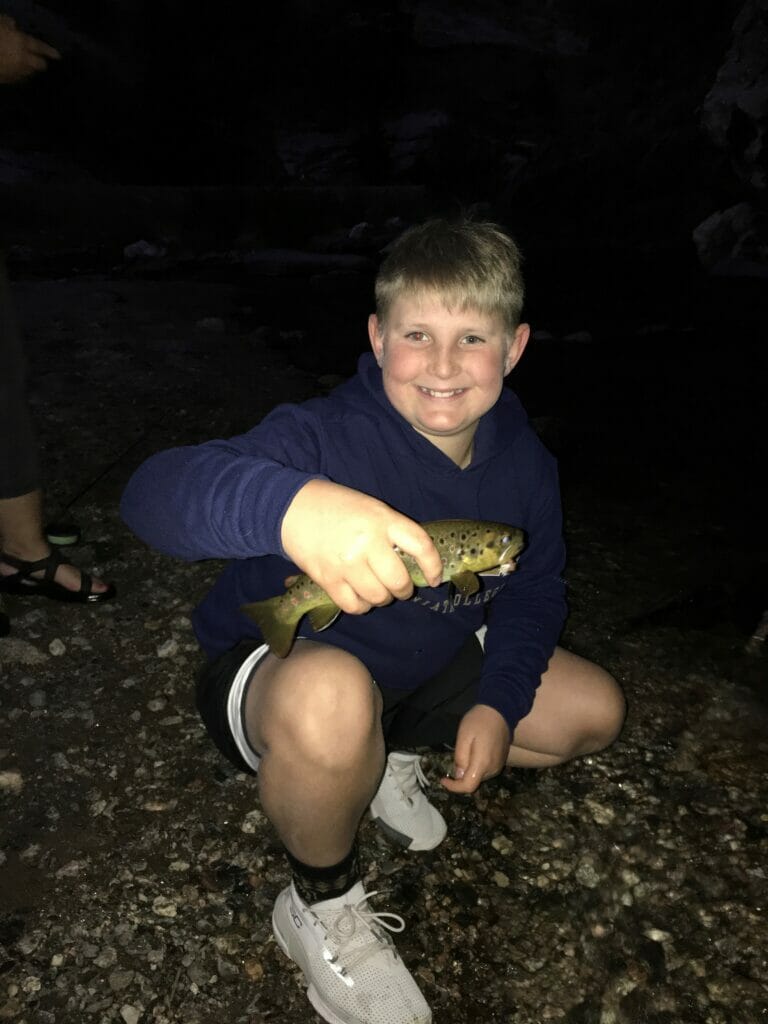

During the COVID-19 pandemic, Geoff Elliot, youth education coordinator with Colorado TU, and his family got the opportunity to explore the national forest areas surrounding their home in Glen Haven, Colo.

This included frequent fly-fishing trips to the North Fork of the Big Thompson River and opportunities to explore new trails in the area. They previously overlooked these areas due to nearby Rocky Mountain National Park and the surrounding larger fisheries, but with travel restrictions imposed during stay-at-home orders and the closure of the park, these neighborhood public lands became familiar escapes from the stresses of the pandemic. As restrictions and closures are slowly lifted, Geoff, his wife Rachel, stepson Leo, and the family dog Henry continue to frequent these local areas and feel an increased ownership over the stewardship of these public lands.

Geoff Elliot is a youth education coordinator with Colorado TU.

Canoeing and fishing in northeast Oregon

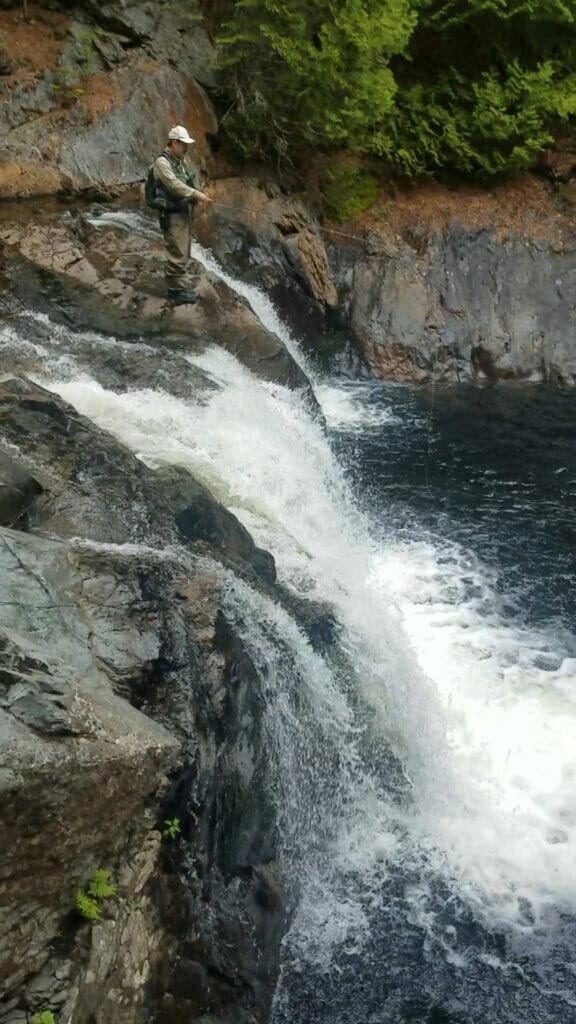

One of TU’s stream restoration specialists has been getting out on her local public lands to explore. Catalina Burch recently spent time on Ross Lake in the North Cascades National Park on a three-night canoe trip with her partner.

They portaged their boat down about a mile and a half of switch-backing trails and canoed 20-miles round trip. They found that portaging a boat down a trail is an excellent way to hike while socially distanced since there is no way for someone to accidentally get within six feet of each other, and there is a built-in face shield! the pair caught and released a couple of good sized rainbow trout and had an all-around blast while accomplishing #responsiblyrecreation in their backyard.

CatalinaBurch is a stream restoration specialist.

Learning about mining sheds light in Alaska

After a busy couple months working on TU’s efforts against the proposed Pebble Mine, a much-needed long weekend brought the opportunity to explore new public lands in Alaska.

My sister and I packed up my car headed to McCarthy on traditional Ahtna native land, the town at the base of the Kennecott Mines National Historic Landmark, nestled in the heart of Wrangell-St. Elias National Park and Preserve.

We opted to take a historical tour of the Kennecott Mine, where we learned that from 1911 to 1938, nearly $200 million worth of copper was processed by people who came to work at the mine.

But in our tour, we also learned that the copper in this region is unlike the Pebble deposit. The Pebble deposit is extremely low grade ore with 0.34-percent containing copper, whereas the Kennecott deposit was more than 70-percent pure copper. The day after the tour, we hiked up to the Jumbo Mine site, where we found chunks of copper on the side of the trail where we stopped to eat lunch. From this visit to public lands, I was reminded that not all mines are like Pebble — the ones that are economically viable, supported by local communities and scientifically proven to be compatible with Alaska’s powerhouse fisheries are benefits to Alaska’s economy.

— Meghan Barker, Pebble Mine organizer

Generations explore brook trout habitat in Maine

For as long as I can remember I have been making the journey to the Cold Stream Forest Maine Public Reserved Lands. Some of my first memories are standing next to Cold Stream with my father and grandfather. It’s where I learned to fish then later to fly fish. It’s where I learned what a brook trout was and where one lived. Every year we made at least one trip, whether to fish the gorge, fish one of the ponds or to shoot at partridge.

But this year was different. My father and I once again made the trip into Cold Stream Gorge, this time to show me a place he remembered from growing up — the Dog Hole. The stream looked exactly like it always had — while the world around us was spiraling into a global pandemic — this slice of Maine had remained unchanged. The brook trout, the trees and the clean, cold water were blissfully unaware of the ongoing hysteria in the rest of the world. That connection to nature became all the more special and a way to escape from the madness that had engulfed us.

While Cold Stream Forest Maine Public Reserved Lands have always been an important part of my life, 2020 has made me appreciate how truly special it is.

— Phil Allen, a member of TU, a Boy Scout high school student, and lifelong trout bum. I live in central Maine and never miss an opportunity to go fishing or duck hunting.