For much of the last six years, Shane Anderson and his team at Swiftwater Films spent thousands of hours meticulously documenting the epic story of the long campaign to reconnect the Klamath River. They’ve gathered hours of historical footage, filmed key moments and celebrations and conducted hundreds of interviews with tribal leaders, conservationists, anglers, scientists and members of local communities.

With exclusive access to the dam sites provided by the Klamath River Renewal Corporation (KRRC), they filmed the reservoirs being drawn down, the two-year dam demolition process, and work to seed the former impoundments with native plants.

In the weeks after breaching the last barrier, sonar detected salmon-sized shapes above Iron Gate. When the call came about the fish seen in Jenny Creek, the first major tributary entering the Klamath mainstem upstream of the former Iron Gate Dam, Anderson immediately packed his gear and hit the road. He arrived at dawn the next morning and soon found the lone fish, a female Chinook who calmly dug a redd while Anderson carefully filmed.

A sight worth waiting for

Salmon hadn’t spawned in Jenny Creek for more than 60 years.

“It was incredible,” Anderson said, recounting the quiet morning alone with the fish. “Nobody knew how long it would take for salmon to find their way above the dams, or how many might show up. But they arrived almost immediately. In the coming days Jenny Creek filled with fish, and further upstream in Oregon, salmon also returned.”

In the days that followed, the Swiftwater team worked to record the arriving salmon. Like other key moments the team documented, Anderson shared the photos with Klamath campaign partners and the media. The images spread widely, appearing in newspapers, on social media and television. Trout Unlimited shared them with our members multiple times.

The photos are profoundly inspiring; a testament to the power of coalitions and the resilience of rivers and native fish. And a perfect demonstration of Anderson’s commitment to bringing conservation stories to the public.

A love of rivers and fish

Long before he was working to document the largest dam removal in history, Anderson grew up an athletic kid in Olympia, Wash. He gained his love of rivers and fishing from time spent on the water with his uncle, renowned rod builder Kerry Burkheimer.

Also a skilled archer, Anderson eventually set a national young adult field archery record in 1994. After achieving such a feat, he soon realized mountains were his primary obsession.

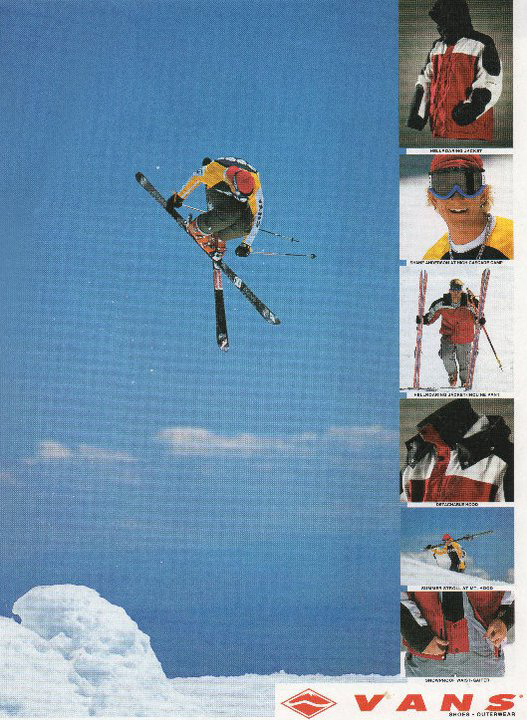

A talented skier, Anderson moved to Lake Tahoe to pursue more time in the mountains and soon skied professionally. He competed across the world, part of a community of skiers pushing the limits of tricks, flips and heights.

In 2000, tragedy struck when a sudden gust of wind threw Anderson 100 feet during a practice jump at the X-Games. He broke his back when he crashed to the ground. Anderson attempted a comeback over the next two years, but found each season cut short by knee injuries.

When the door closed on his skiing career, Anderson moved to Hollywood to pursue opportunities in the entertainment industry, hosting skiing shows for television, working on film crews and doing voiceover work. He also rekindled his love of fly fishing.

“During the years I was injured, friends started bringing me up to the Trinity and Klamath basins,” he explains. “I reconnected with steelhead fishing and just fell in love with rivers.

“I was also learning about the impacts of dams and how many of California’s wild and salmon steelhead populations had been lost in such a short period of time.”

The loss made him angry, and he knew he wanted to do something about it.

Putting anger into action

At the same time as his opportunities in Hollywood felt like they were fading, Anderson was growing inspired by the ability of documentaries to educate audiences and connect to their emotions through film. He admired the environmental activism of his friend Daryl Hannah, but he wanted to find a way to work on the stories and issues that resonated the most for him.

Anderson shifted gears again. He moved north to Humboldt and re-enrolled in college. He took video production classes while studying to become a fisheries biologist. During these years, video technology changed quickly, and the barrier to entry for independent filmmakers grew more accessible and less expensive.

“I had an epiphany one night,” he explains. “I was listening to a podcast describing the state of wild steelhead on the Olympic Peninsula and I couldn’t believe it; I knew then what I wanted to do. I wanted to move back to Washington and spend a year making a movie about steelhead because that’s what I love, so I bought a camera and that’s what I did.”

“Wild Reverence: The Wild Steelhead’s Last Stand,” Anderson’s first full-length documentary opened to audiences in 2014.

Storytelling’s impact

Wild Reverence kicked off an intense decade of work and growth for Anderson. When “Undamming Klamath” is released this fall, it will be his eighth feature-length documentary. He has also made over 70 short films.

Anderson has told stories about the opportunity to restore California’s Eel River and a proposed dam looming over Washington’s Chehalis Basin.

He worked with TU to celebrate the return of the Elwha River’s wild summer steelhead following dam removal.

In “The Lost Salmon,” he explored new genetic research unlocking the key to saving spring-run Chinook and the salmon’s connection to the Pacific ecosystem and culture.

He partnered with the Nez Perce Tribe to make “Covenant of the Salmon People,” a powerful look at the Tribe’s connection to the landscape and the need to remove the four lower Snake River dams to prevent salmon extinction.

Other short films highlighted habitat restoration projects, river and forest protection efforts and selective commercial fisheries.

Countless film festivals screened Anderson’s documentaries. They were broadcast nationwide on public television and used in curriculum at schools and colleges. In 2023, attendees to TU’s CX3 event in Spokane, delighted at watching the “Covenant of the Salmon People”.

Thanks to social media, millions viewed Anderson’s work as the dams came down. The timelapse footage being the most watched.

Along the way, Anderson won numerous awards, including a pair of regional Emmys.

Films used as a force for good change

Salmon and steelhead, rivers, forests and ecology are constants throughout his body of work. The films themselves are a mix of advocacy, education, science and celebration of the ecosystems, fish and communities who depend upon them.

Over the last decade, Anderson has worked hard to improve his craft. The cameras improved, the footage more beautiful and his interviews and storytelling have grown more insightful. For all the focus on salmon, steelhead and the resilience of nature, the lasting impact of his films might be their growing emphasis on community as the ultimate force for change and restoration.

“Coming out of ‘Wild Reverence,’ it blew me away how polarizing the conversations could become in policy meetings but also how powerful it was to screen the film, sit in those spaces with people and have discussions afterwards,” Anderson explains. “Over time it has become clear to me that building coalitions, and searching for our shared humanity, is always how we actually reach our shared goals.”

Dam removal on the Klamath River embodies this insight. Salmon are once again returning to historic habitat because of the tribal leaders, conservationists, anglers, scientists and many others, who were never willing to accept anything less than a reconnected basin.

Swiftwater Films’ account of this story, “Undamming Klamath,” is planned for release in autumn 2026. Learn more about the project, and how to support the production, at The Redford Center.

A personal connection to nature

Throughout his career as a filmmaker, Anderson has sought time spent outdoors as crucial moments to recharge and reflect. When he needs to get out from behind the camera, or away from long days of editing and managing logistics at the computer, he heads to the river, the coast or the mountains. Depending on the season, he might be fishing, surfing or backpacking far into headwater valleys. In the winter, he still manages to ski a few days, too.

“A project like the Klamath film is a massive puzzle. You can get tunnel vision, but getting into nature, finding focus and settling into the rhythm of the natural world has always been how I keep my sanity. Some of the best ideas and solutions can happen there,” Anderson explains.

Steelhead fishing on Northern California rivers remains a passion and source of inspiration for Anderson. Usually that means summer and fall days on the water, casting a floating line on a 5 or 6 weight two-hand rod built by his Uncle Kerry. Almost always, he’ll be fishing a muddler.

The same free-flowing rivers that sustain trout and salmon bring clean water into our homes, give life to vibrant communities and feed a passion for angling and the outdoors.

But today our fisheries and rivers face enormous challenges. At Trout Unlimited, we are doing something about it, and we need your help. Sign up to be a champion for the rivers and fish we all love and help us unlock the unlimited power of conservation.