USFS scientist Nat Gillespie’s formative years fostered his desire to champion river health across the country

The metro DC area isn’t exactly an outdoor mecca, but outdoor adventure is where you find it.

As a kid growing up in Alexandria, Va., Nat Gillespie found plenty.

“My parents were free-range,” Gillespie recalls. “They allowed me to go explore. They would drop me off at the river when I was 12 years old with my friends, and I just learned it on my own.

“It was urban fishing. Golf course ponds. Bass and catfish in the Potomac. And, every chance I got, trips to the Shenandoah National Park area and the Catskills, where my family has lived for almost 200 years.”

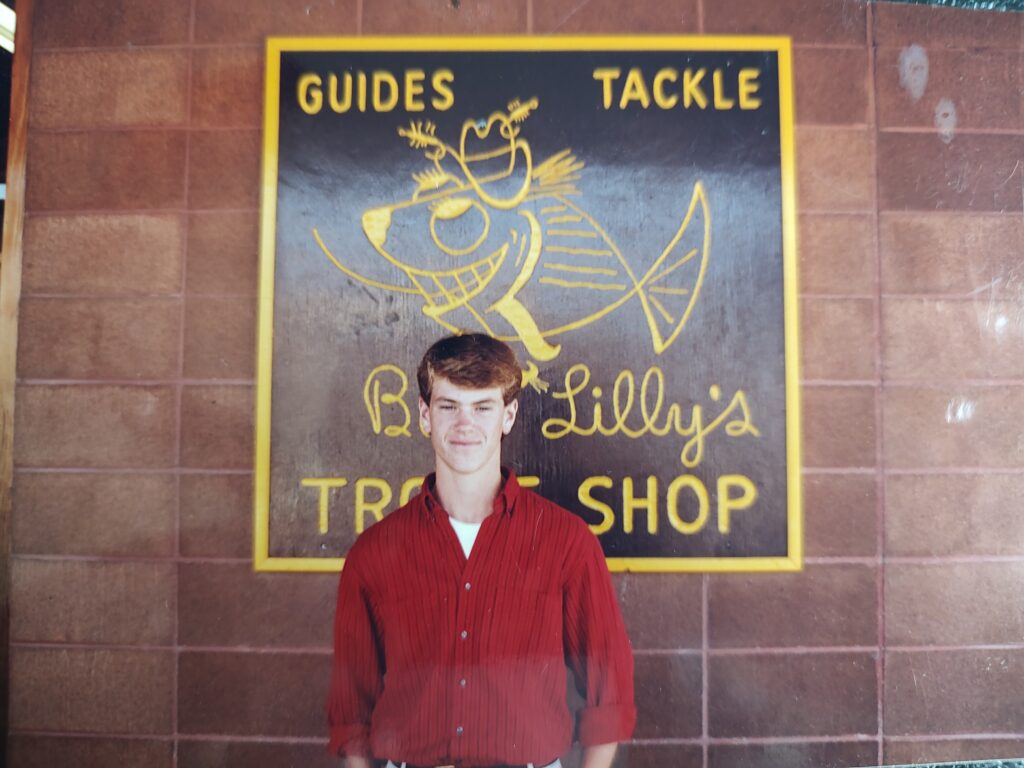

Gillespie also spent two high school summers on his own working at Bud Lilly’s Fly Shop in West Yellowstone.

He learned well; those early days of river and creek stomping forming a foundation for a career grounded in the wild as a champion for our nation’s rivers, from an early stint as a project manager with Trout Unlimited to his current job as the acting director of the Forest Service’s fisheries program.

How big is that job?

Think 220,000 miles of fishable streams and rivers—comprising 50 percent of salmon and trout habitat in the Lower 48—and more than 10 million acres of lakes, ponds and reservoirs.

Never a dull moment

Gillespie’s home base has been the Forest Service’s headquarters in DC since he joined the agency as the assistant national fish program leader about 15 years ago. He’s had many temporary details far afield; those assignments helping him further gain an appreciation for just how vast and varied the agency’s resources are.

“It’s 193,000,000 acres, so it’s just there’s so much going on in terms of fisheries,” he said. “With cold water, warm water, salmon, all kinds of ESA-listed fish and mussels and invertebrates.

“It’s never a dull moment. Literally.”

It’s a lot different from Gillespie’s first gig after graduating from Williams College.

“I did an environmental consulting job for about a year and a half in Connecticut, cleaning up industrial waste,” he said. “It was a great intro to groundwater and geology and chemistry, but I realized I wanted to be on the conservation side.”

And that’s what he got when TU hired him to lead its nascent Home Rivers Initiative on New York’s Beaverkill River.

“I learned a ton on the job working with a wonderful mentor, Jock Cunningham,” Gillespie said. “I was outside surveying rivers, counting bugs, measuring sediment and working with the community on lots of local issues. Lots of flood damage, road issues and it’s a huge fishing economy.

“It was a crash course in geomorphology and fantastic training.”

Longtime TU staffer Amy Wolfe was among those impressed by the young project manager.

“I first met Nat over 20 years ago, and I’ve valued every opportunity to collaborate with him since,” said Wolfe, TU’s Northeast regional director. “His expertise and unwavering support for coldwater conservation go beyond professional commitment—they are emblematic of who he is, and that makes a truly meaningful impact.”

TU and beyond

After a three-year run, Gillespie left TU to go to graduate school at the University of Michigan’s Natural Resources program. But then he was back to TU, this time working on the science team under the tutelage of Jack Williams. That lasted seven years before he moved on to the Forest Service.

The Forest Service has provided Gillespie with lots of opportunities to work on balancing fisheries needs with other demands for the land. And because the Forest is one of TU’s most important partners, Gillespie still gets to spend plenty of time working with TU in pursuit of the shared mission of caring for and recovering watersheds and the fish that rely on that cold, clean water.

“I really enjoy working at the Forest Service because I’m really in tune with and support the mission, which is multiple use,” said Gillespie, who is 51 and lives in the District with his wife and their two teenagers. “The goal is to use the land productively, and to manage it in a way that protects water quality and water availability, to protect fish and wildlife, to manage recreation and to produce things for society.”

That management is intertwined with addressing legacy impacts on the land, from mining to timber operation to existing infrastructure such as roads, particularly when those roads cross streams.

TU is a frequent partner with the Forest Service on road-stream crossing projects, such as replacing aged, damaged or undersized culverts with structures that will handle vehicle traffic without creating barriers to fish passage. Those culvert projects not only improve watershed health by improving habitat for trout and other stream dwellers, but they help streams function more naturally and improve flood resiliency, which pays off for communities through which the streams pass.

Improving flood resiliency is becoming increasingly important as storms become more frequent and more severe as our planet’s climate changes.

“TU has been a real leader in the conservation community in how we’re looking at flooding, and how we’re managing flooding in terms of protecting fisheries and trout and salmon habitat,” he said. “I don’t think it was planned out that way, but it’s certainly clear now that fish passage implementation and prioritization brings with it flood resilience and economic benefits to society.”

Still out there finding fun

Despite the demands of his senior role with the Forest Service, Gillespie still finds time for outdoor fun with his family, and is trying to instill in his kids the same appreciation that he gained at young age from his parents and important mentors like his grandfather, who taught him to flyfish decades ago during those family trips to the Catskills.

“My wife is from Maryland, but we met at grad school in Michigan,” he said. “We have a son who’s 15 and a daughter who’s 12. They’re out with us as much as possible, hiking, fishing, hunting, looking for mushrooms and antlers. In a city like DC you have to work a little harder to expose them to nature, but it’s doable.”

Gillespie knows that he’s fortunate that his passions and career are so aligned.

“One thing about working at an agency like this, the Forest Service is full of incredible expertise across so many disciplines,” said Gillespie, for whom the diverse mission still connects back to both his professional role and his personal passion. “For someone with a curious mind, I’m learning constantly about new things, like wildfires, timber and vegetation from some of the most skilled scientists and land managers in the country.

“It’s all fascinating and it all relates to watershed ecology—how we treat the land ultimately finds its way downhill and into the stream, which is what a fisherman wants to understand.”

Not physically distant from Washington DC but a world away from the hustle of the big city, the George Washington and Jefferson National Forests and Shenandoah National Park together offer nearly 2 million acres of public lands to explore and thousands of miles of tumbling mountain streams home to native brook trout.

Finding trout water is as simple as looking for blue lines in your favorite map book, referring to the Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources searchable trout water database or firing up your favorite trout app.

You can fish all year, but the best action is in spring and early summer, when water levels are at their best and hungry brookies will slash at just about any well-presented dry fly. Just make sure to be stealthy, because if you cast a shadow on a pool or make a splash with a clumsy cast, these wary critters will head for an under-rock hiding spot in a flash.

The same free-flowing rivers that sustain trout and salmon bring clean water into our homes, give life to vibrant communities and feed a passion for angling and the outdoors.

But today our fisheries and rivers face enormous challenges. At Trout Unlimited, we are doing something about it, and we need your help. Sign up to be a champion for the rivers and fish we all love and help us unlock the unlimited power of conservation.