Healing a river takes time. It takes skill and knowledge. It takes funding and resources. It takes communication and partnership building.

Most importantly, it takes planning, passion and persistence.

For Clear Creek in Colorado and LaBarge Creek in Wyoming, Trout Unlimited volunteers and staff have brought all of those needs together thanks to two Embrace A Stream grants helping them bring their vision of restored rivers to life.

A bit of Embrace A Stream history

Since 1975, Embrace A Stream, TU’s longest running grassroots grant program, has helped volunteers across the country be champions for the local rivers they love by providing more than $5 million to 1,250 volunteer-led projects.

“Trout Unlimited volunteers are a lot like St. Jude, the patron saint of lost causes, because they take on the hard problems that others avoid—the rivers that need the most help and the longest, most consistent care and attention,” said Jeff Yates, senior director of engagement. “Embrace A Stream has helped thousands of people be champions for their local rivers and care for and recover them over decades—sometimes across generations—if that is what it takes to bring them back.”

A reel helps provide funds

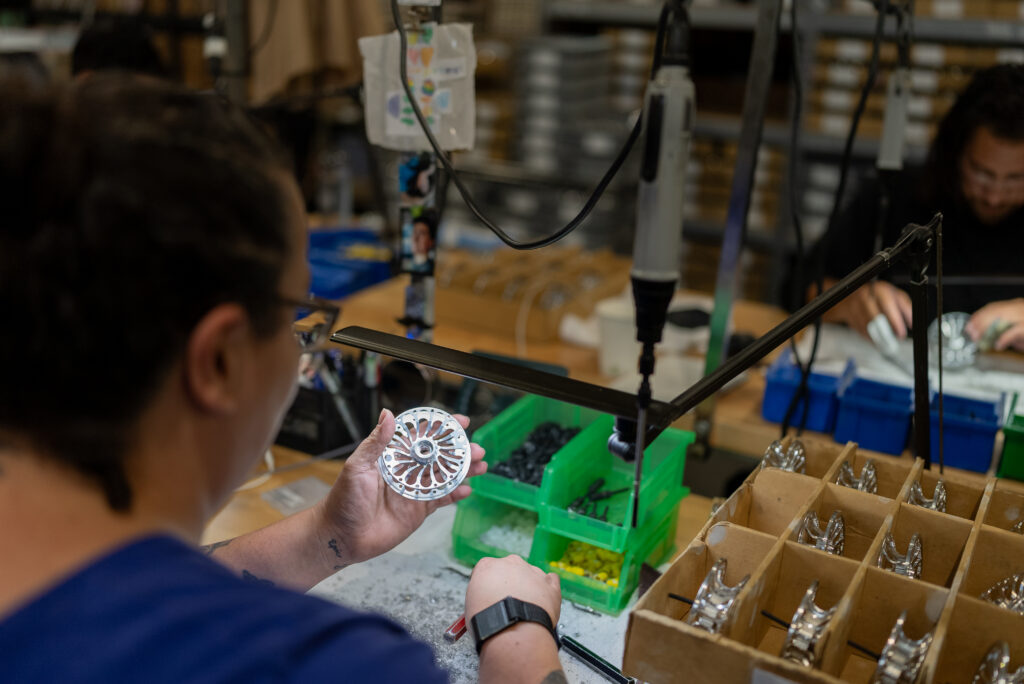

Four western waters—Clear Creek, La Barge, the Big Hole in Montana and the Provo River in Utah—received an additional investment of $100,000 recently thanks to a partnership with Mayfly Outdoors and Molson Coors who have launched a limited-edition reel collaborative to benefit the Embrace A Stream program.

Fueled by the funding, projects on these waters are already making an impact.

Bringing back La Barge for native Colorado River cutthroat

Flowing nearly 68 miles from the high peaks of the Wyoming Range and the Bridger-Teton National Forest through a 47,000-acre watershed and into the Green River, La Barge Creek is making a comeback as a stronghold for Colorado River cutthroat. The road to recovery, however, will be as long and winding as the hundreds of oxbows in its willow-lined course.

“The LaBarge Creek restoration story is a complicated one with many wins and losses for Colorado River cutthroat trout,” said Nick Walwrath, TU’s Green River senior project manager. “Getting anglers out on the stream working alongside the biologists and getting hands-on experience in the efforts taking place on LaBarge Creek will be key in turning this project into a success story.”

In the early 2000’s, La Barge was the site of one of the largest brook trout removal projects in the state. More recently, whirling disease has been discovered in the river—an issue thwarting the recovery of the native fish.

For TU volunteers, staff and partners from state and federal agencies, the work to recover this iconic river is already decades-long, and with the funds from Embrace A Stream they are redoubling their efforts.

This past summer, nearly a dozen volunteers from Wyoming Trout Unlimited joined TU staff and biologists from Wyoming Fish & Game for a community science weekend of fish population surveys, spawning redd mapping and camping along La Barge. It’s critical data the state is using to develop a larger, watershed-wide plan for recovering the river.

Community engagement is a critical part of the La Barge restoration plan—as angler awareness, advocacy and action will be required to stem the impacts from disease and habitat loss and turn the tide for this river.

“There has been a lot of misinformation surrounding the work that has been done and the work that is being done. This type of project is what the Embrace A Stream program is all about,” said Walwrath.

The work continues this coming summer, with a return trip to La Barge for volunteers to assess the current population health, determine if there have been shifts or improvements in spawning activity and install educational signs along the most popular fishing and camping stretches of the stream so that everyone using the river can be aware of their impact on habitat loss and reduce the spread of whirling disease.

Cooling & cleaning Clear Creek for the fish and the community

Fed by mountain streams tumbling off 14,000-foot peaks near the Continental Divide in Loveland, Colorado, Clear Creek carves its way through rocky mountain passes and a canyon as it flows down to the valleys surrounding Denver and into the South Platte River.

Along the way it passes through the very center of the historic Molson Coors brewing facility in Golden, where the company famously “taps the Rockies” to make its beers.

While one-third of the watershed lies within the Arapaho & Roosevelt National Forests, and the upper reaches of Clear Creek are teeming with wild trout, the watershed suffers from a history of impact. At least 1,600 abandoned mines dot the watershed, leaking toxic runoff that turn tributaries bright orange and keep life at bay—particularly aquatic insects and trout.

A top-to-bottom approach to restoring Clear Creek has been moving forward since the early 1990s, and much progress has been made in that time to clean up mines and improve habitat.

For the West Denver Chapter and its members, caring for Clear Creek is as much about connecting residents in the suburban and urban communities to the river as it is about protecting the wild trout in its headwaters.

“I grew up in Colorado, I grew up in these watersheds and spent my whole youth bumping around in these watersheds,” said Ashley Giles, the chapter president. “We talk about coldwater fisheries in TU, but in the modern age we all know that it’s a connected system.”

Armed with an Embrace A Stream grant, and in partnership with the city of Wheat Ridge, the chapter-led riparian planting is part of a 7-mile restoration effort along a 300-acre complex of parks and trails. While not home to wild trout, this section of river connects thousands of park users to the river and increases their awareness of and support for the important work far upstream.

“It’s so exciting to see people get the chance to come into a setting like this, make a difference and give back to these streams that give so much to helping nurture our spirit as well as our environment,” said David Nickum, executive director of Colorado TU.

The native trees planted will shade and canopy Clear Creek, helping lower its temperature. As they grow and mature, their roots will stabilize streambanks from eroding, slow stormwater runoff and filter out pollutants from nearby parking lots and roads.

More importantly, they will stand as reminders that the community can come together to embrace a local river and make a meaningful, measurable difference. It’s just one part—but an important one—in the long road to recovery and restoration for Clear Creek.

Up next: Fire recovery on the Provo River and fish passage on the Big Hole

This coming summer, TU chapters and staff will continue putting the Embrace A Stream resources to work in Montana and Utah.

In the Provo River watershed in Utah, the High Country Fly Fishers Chapter in partnership with TU staff and the U.S. Forest Service will be working to restore Soapstone Creek—an important tributary to the Provo—where the 33,000-acre Yellow Lake Fire destroyed large swaths of riparian habitat along the river. The volunteers and partners will be installing beaver dam analogs and planting native willows, shrubs and meadow plants to restore the streambanks and capture soil and ash runoff from the upland burned area to prevent damage to the health of the creek.

Along the Big Hole in Montana, fish passage, which has been blocked by irrigation diversion for decades, will be restored to Johnson Creek by the George Grant Chapter and our Montana Council staff. The project will reconnect critical spawning habitat not only for Westslope cutthroat trout but also for Arctic Grayling, which are beginning to re-inhabit this section of the Big Hole thanks to significant partnership work in the watershed.