Study of past data shows declines are steep; more closures in Washington and elsewhere may become the norm.

Last week, steelheaders in Washington State were dealt another tough blow with the early closure of the coastal winter steelhead season.

Anglers in this region were already fishing under a second season of emergency regulations, implemented in response to concerns about declining runs. But a number of in-season management indicators showed that, by late February, the actual run was about 30 percent below forecast, forcing both Washington’s Department of Fish and Wildlife and coastal treaty tribes to close their fisheries on March 1.

The downward trend for steelhead on the Olympic Peninsula and Washington’s coast is an unfortunate reality of recent times.

It’s hard not to think about all the chrome we’ve missed as a result of being too late to the party.

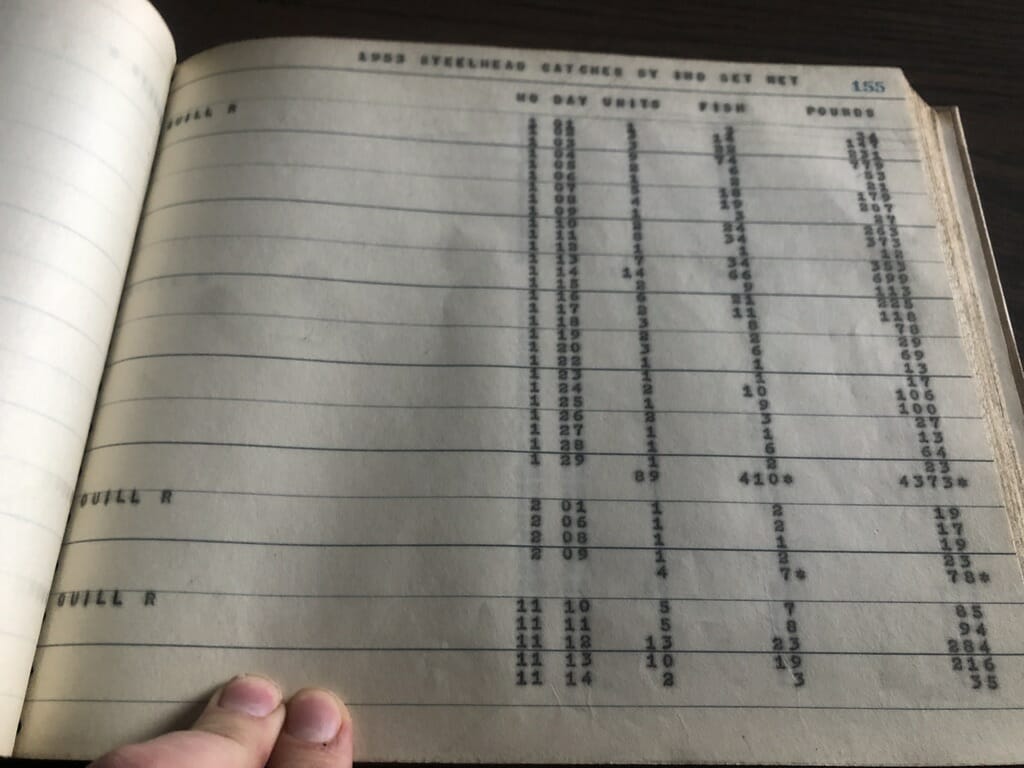

How late? Thanks to a new study, anglers (and, more important, fishery managers) now have a better sense of how many steelhead once returned to these fabled rivers and when. Last year, John McMillan, then-science director for TU’s Wild Steelhead Initiative, teamed up with Matthew Sloat of Wild Salmon Center and Martin Liermann and George Pess of NOAA Fisheries Service to examine historical catch record data of wild steelhead on Washington’s famed Olympic Peninsula.

Their report, which was published in the North American Journal of Fisheries Management, analyzes historical data from 1948 to 1960 to provide a more accurate picture of what we witnessed with wild salmon population numbers from 1980 to 2017, and what we’re seeing today.

Their findings were eye-opening.

Analysis of the historical catch records showed that the wild steelhead populations on the OP have declined on average by more than half, and that fish now return to freshwater an average of one to two months later than they did 70 years ago. Modern wild steelhead runs are also shorter in comparison to the 1950s.

McMillan sat down with the writer Geoff Mueller to talk about how the study came together, what the team learned, and what it all means.

Q: Give us some background on the project: How did you become involved?

I’ve been aware of historical catch data for Olympic Peninsula steelhead for quite a long time, and back in the early-2000s there were a couple reports that used historical fishing data to evaluate potential changes in run timing and population size. Those reports were never peer-reviewed, however, and as the years passed, I began to realize that many people were simply unaware that the populations had potentially changed, and so I discussed the concept of publishing the data with a couple of colleagues.

After we talked about the potential for analysis, we all agreed that the information would be helpful to understanding what populations of OP wild winter steelhead once looked like. For example, a lot of scientists and anglers are unaware of the historical extent of early-entering wild winter steelhead, and consequently, we had come to accept the status quo as the norm. This is what we refer to as the Shifting Baseline Syndrome, and the only way to change that is to generate historical estimates of run timing and run size.

Q: Why is this historical context important?

A historical context is important because we often rely on modern data sets, and while those are important, they don’t inform us about what the populations looked like before the onset of modern monitoring programs. On the OP, monitoring of wild steelhead didn’t really begin until the late-1970s to early-1980s. By that time, there had already been a great deal of fishing and in some populations, extensive hatchery releases.

As a result, it was often assumed that the population sizes and run timing documented at the beginning of the modern monitoring period were reflective of historical run sizes and run timing. And consequently, it was also assumed that the early-timed hatchery programs, which selected for adults returning in November-early-January, largely occupied a run timing niche that wild winter steelhead did not.

Our historical analysis suggests that there were differences in both run size and run timing, and that wild steelhead now enter later than they once did and consequently, the run timing has become more compressed. Further, it appears run sizes were much larger historically. In this context, we now have a better understanding of historical run size and timing, which provides benchmarks that can help alleviate the “shifting baseline.”

Q: No matter how you slice or dice the data, Olympic Peninsula’s wild winter steelhead populations are suffering. This season as with the last, we are seeing river closures and emergency fishing regulations introduced across OP wild steelhead fisheries. How do these findings play into our understanding of this dire picture?

I think a longer-term data set provides a better perspective on these populations. For instance, these stocks have long been considered to be healthy, at least until very recently. One reason for this is that scientists and managers didn’t have a sense of the historic run size and timing of the steelhead populations. So in that sense, our results suggest the populations are in worse shape than initially thought.

Q: And based on the findings, do you see a need to reevaluate recovery goals and strategies?

Although the historic data suggest the populations are in longer term decline, the results also suggest there are ways we can help the populations. Rebuilding early returning life histories could increase their diversity and help spread risk across a greater range of adults. Basically, increasing diversity helps increase their portfolio of life histories, which in turn is known to improve population stability and resilience. But, it also suggests that we may have underestimated the productive capacity of the watersheds and the populations.

To learn more about this study, including a link to the full study, check out the two-part series on the Wild Steelheaders United blog here and here. For those looking to really peek under the hood on the research, check out McMillan’s Science Friday post on the WSU blog here.