The Weber River is an important trout fishing destination in northern Utah offering excellent angling opportunities and provising a home for unique native fish species at the same time.

Trout Unlimited started the Weber River Restoration Program seven years ago to improve fishing and increase native populations.

Fluvial (migratory) Bonneville cutthroat trout in the mainstem of the Weber grow large and spawn exclusively in small tributaries of the river and are an incredibly important resource to local anglers. In addition, the Weber River supports a little-known species called the bluehead sucker, which has experienced dramatic declines over the past 30 years, reaching critically low population levels.

A sampling report from the 1920’s indicated the bluehead sucker was historically very common throughout the basin, with more than 700 fish being reported in a single pool. Now population estimates are around 1,200 total fish in the entire river.

Understanding the declines and limiting factors for both species is key to our success in the Weber River.

Until our restoration program began, we didn’t realize the true scale of challenges this amazing river has faced for decades. The habitat has been severely degraded over time and was initially caused by the construction of the railroad, which confined the floodplain along the path of the tracks.

The Weber River and its tributaries are home to unique native fish species, but also offer some great fishing opportunities.

Then came the construction of Interstate 84, which straightened miles of the Weber throughout the basin. Finally, land management and urban encroachment continued to put increasing pressures on the river system.

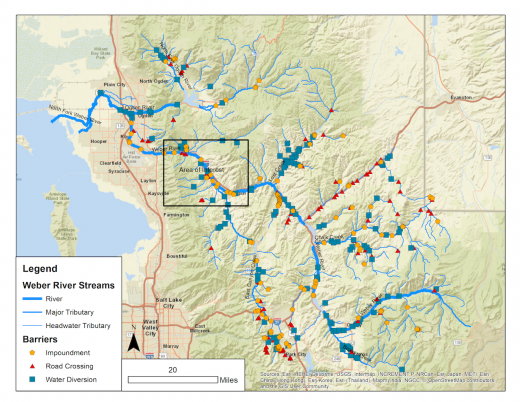

The Weber has also been highly fragmented. Habitat has been chopped up by 396 barriers composed of road crossings, impoundments and irrigation diversions; breaking the habitat into isolated reaches of stream fish are no longer able to move between. Because river networks are linear in nature, fish must follow these pathways to access different habitats at different times of their life cycles. Fragmentation is a widespread challenge in many rivers across the United States and prevents many fisheries from reaching their full potential. We recognized this challenge in the Weber River and have focused our primary restoration strategy on improving habitat connectivity for migratory cutthroat trout and Bluehead sucker, but with the scale of fragmentation and degradation in both the tributaries and the mainstem, the only way to make significant improvements to this fishery is through collaborative efforts.

This fall we completed two projects in the lower Weber River that are a result of collaborative actions and are meaningful to the fishery. These projects could not have happened without financial and collaborative partnerships.

Upper Jacobs Creek Culvert

Jacobs Creek is the most important spawning tributary for the fluvial Bonneville cutthroat trout population in the lower Weber. In 2013, when we began mapping barriers, we identified two road culverts approximately 400 feet apart from each other immediately upstream of its confluence with the Weber River. The culverts blocked migrating cutthroat trout from spawning in Jacobs Creek. Identification was the first step, but knowing where on the landscape the barriers were relative to other barriers, has allowed us to be strategic about barrier removal. When Questar (now Dominion Energy) needed to replace their pipeline along the Weber and across Jacobs Creek, we collaborated with them to replace the lower road crossing as well.

The upper culvert also represented a challenge to migrating cutthroat trout. Data from the Utah Division of Wildlife Resources indicated about half of the fish attempting to migrate up Jacobs Creek were blocked from high quality spawning habitat by this culvert, which was associated with an access road for the Weber Basin Water Conservancy District, a major water supplier for people on the Wasatch front.

A limited number of cutthroat trout attempting to access the headwaters of Jacobs Creek could make it past this barrier. Paul Burnett/Trout Unlimited

Recent collaborative efforts in the Weber have begun to break down communication barriers that existed between the fisheries and water management interests in the basin. This new era of collaboration has allowed TU to team up with nontraditional partners to make conservation gains for fisheries. Restoration at this specific culvert on Jacobs Creek is an example of those efforts.

TU identified this culvert as a priority and reached out to project partners for support. We were fortunate that a wide range of partners including Dominion Energy, the Western Native Trout Initiative, Weber Basin Water Conservancy District and the Utah Division of Wildlife Resources were interested in working with us. TU developed a design, which was to construct six 15″ drops every 10 feet to break up the large vertical drop at the tail out of the culvert. Through a Bureau of Reclamation WaterSMART grant the Weber Basin Water Conservancy district provided full construction support with their staff. Additional funding came from the Utah Cutthroat Slam, a partnership between the Utah Division of Wildlife Resources and Trout Unlimited.

Pools created below the barrier opened up headwaters of Jacobs Creek so migratory cutthroat could reach historic spawning grounds. Paul Burnett/Trout Unlimited

The Bonneville cutthroat trout in the Weber River now have full access to 2.5 miles of spawning habitat. Although it seems inconsequential to reconnect a tiny stream to the Weber River. Streams like Jacobs Creek provide critical spawning habitat which sustains this important fishery. More available spawning habitat means more juvenile cutthroat moving into the Weber River mainstem where they can grow and provide an important native trout fishery.

Pentz-Smith Diversion

Another project completed this fall was the reconstruction of an irrigation diversion on the mainstem of the Weber River near the town of Morgan, Utah. Why would TU be interested in reconstructing a water diversion? The answer lies in the concept of improving and maintaining habitat connectivity through cooperative, nonregulatory means. TU and our partners are quickly developing the knowledge on how to build instream structures that provide a myriad of benefits ranging from channel stabilization to fish passage. If we can begin demonstrating that rivers can be managed to meet multiple needs it opens the door to begin working with water users throughout the Weber on the more than 220 diversions that fragment habitat across the basin.

This project was an ideal opportunity to develop a local demonstration. The Pentz-Smith Water Company has been squeezed over time. Where the town of Morgan has expanded, their diversion has been encroached upon by infrastructure. Their water management activities were coming into conflict with this new infrastructure and, at one point, it was possible that their diversion structure was going to be forced to move downstream. To continue getting water into their ditch the water company would have needed to build a 7-foot tall rock dam. This is like other rock dams throughout the Weber River. These dams are problematic for the river. They block fish from migrating upstream, they are unsafe for people, they cause sediment buildup and they are flood risks. Our goal with this project was to reduce the impact on the river by the diversion.

To do this, we maintained the diversion in-place, but constructed two fortified drop structures of 10″ each, which provide grade control protection and allow fish passage around this diversion structure. We also placed filter boulders at the inlet of the canal to reduce a back eddy and filter out large debris from being deposited into the canal. Although these solutions are much more resource intensive, we are confident that they will bring sustainable solutions to the river. Next year will be the test, and we are thrilled to see this project on the ground where it will be an opportunity to share what we have learned about water management with other water users in similar situations.

The Pentz-Smith Diversion, with gentle drops that will maintain channel grade, allow for fish passage upstream and provide additional water security for the irrigation company. The row of rocks on the right hand side of the structure are called filter boulders, which break-up a backeddy that was trapping debris and trash, but will also block larger debris from being entrapped into the diversion canal. Paul Burnett/Trout Unlimited.

Funding for the Pentz-Smith Diversion came from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service’s Partners for Fish and Wildlife, and Fish Passage Programs, The Utah Division of Wildlife Resources, the Lawrence T. and Janet T. Dee Foundation, the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation, and the city of Morgan. The project was designed by RiverRestoration.org and construction completed by Redoubt Restoration.

Looking Forward

2017 brought us many successes in the Weber River. The two projects completed this fall are complimentary to the removal of three other barriers in the basin this year as we continue to make progress on protecting these valuable fisheries. But the need for additional work continues. Fragmentation continues to be a significant challenge in the Weber River and we look forward to making additional progress with our partners in the future.

Paul Burnett is the Utah Project Leader for Trout Unlimited. He is based out of Odgen, Utah, and can be reached at PBurnett@tu.org