California’s Bay-Delta, where the Sacramento and San Joaquin Rivers converge to form the largest estuary on the West Coast, is the hub of both the state’s water supply and the second largest runs of salmon and steelhead south of Alaska.

The Bay-Delta is also the hub of the struggle over how to provide enough water for both people and the environment in California. TU, through our Science Team, is playing an important role in addressing the challenges of this struggle.

In recent years, TU’s California Science Director Rene Henery has led this effort. Henery’s work has been vital to the increasing focus on floodplains as a key tool in restoring fish habitat and populations, and has helped build collaborative efforts to produce on-the-ground results such as the Central Valley Salmon Habitat Partnership.

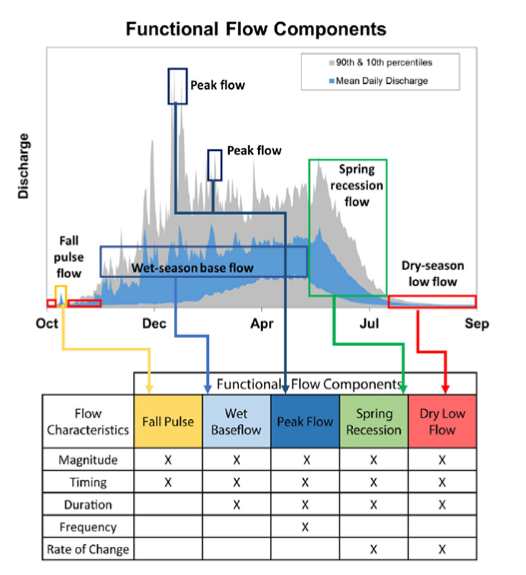

An important concept in water resource management is “unimpaired flows” — in general, those instream flows that would occur during the year if a river had no dams or diversions on it — if its flows were influenced only by natural conditions.

Most major river systems, of course, now have dams and water diversion infrastructure on them and cannot replicate unimpaired flow conditions. However, the science of river ecology and hydrology affirms that, in the absence of unimpaired flow conditions, mimicking the natural variability in river flows is essential to support wildlife species such as salmon and steelhead that have evolved to those ecosystems and to take advantage of the natural variability of those systems.

Henery and other TU Science program staff have played an important role in the development of this science and for a resource management approach for dammed river systems that provides sufficient flows for fish when they need it most.

Henery has just co-authored a post in the influential water news and policy website Maven’s Notebook (with scientists Julie Zimmerman and Jeanette Howard from The Nature Conservancy and Jon Rosenfield of San Francisco Baykeeper), on the importance of managing a river so it can provide “functional flows.”

As defined in recent scientific literature, functional flows are “those aspects of the flow regime that directly relate to ecological, geomorphic, or biogeochemical processes in riverine systems, and all functional flow components must be incorporated into flow prescriptions to be ecologically protective.”

Henery and co-authors make clear that in most river systems it is no longer possible to provide a true natural hydrograph (unimpaired flows). But, they argue, “in most rivers, environmental flows that provide the functions of a natural hydrograph are the best hope to allow native species to persist and thrive.”