TU’s new study shows dam removal is feasible and affordable

After more than three years of engineering work, legal analysis, and other planning, Trout Unlimited has completed an extensive study considering the feasibility of removing the Enloe Dam from the Similkameen River in North Central Washington. This work was accomplished in partnership with the Confederated Tribes of the Colville Reservation and in collaboration with the Okanogan Public Utility District (PUD).

“The completion of the Feasibility Study is an important milestone in the process of evaluating the future of Enloe Dam and the Upper Columbia’s struggling populations of steelhead and spring Chinook,”

explains Micheal Ward, Trout Unlimited’s North Central Washington Senior Project Manager. “The work isn’t over. We’ll keep working closely with our partners to find a collaborative solution that benefits fish and regional communities.”

The Feasibility Study considers about a dozen alternative approaches to removing the Enloe Dam and managing the sediment impounded in the dam’s reservoir. It concludes that at least a few of the approaches are feasible and affordable. The analysis sets the stage for the next process considering options for dam removal to reconnect historical salmon and steelhead habitat in the Upper Columbia, restore access to important indigenous cultural sites, and protect regional ratepayers from ongoing liabilities.

A tribal-led Traditional Ecological Knowledge (TEK) Table is informing the project’s design, ensuring restoration would honor cultural values, first foods, and generations of lived experience.

The Feasibility Study, information about the process, and next steps for project design, planning, and public participation can be found at: www.enloefeasibilityassessment.com/

The work contributing to the Feasibility Study was supported by the NOAA Restoration Center, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Mid-Columbia PUDs, The Conservation Alliance, Resources Legacy Fund and others.

Enloe Dam

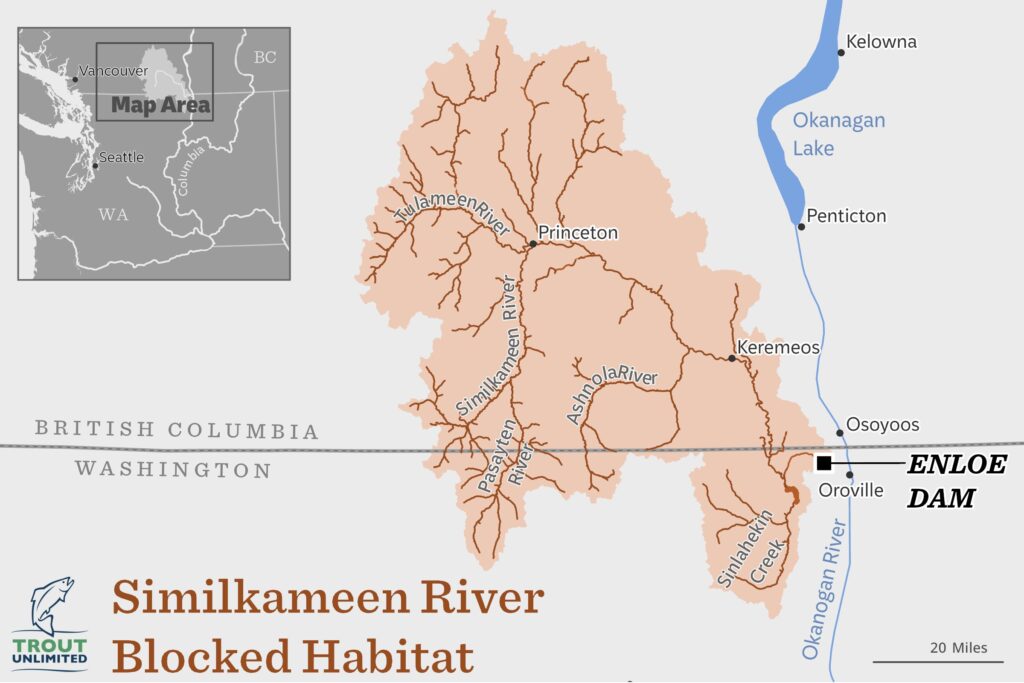

The Enloe Dam, and its accompanying powerhouse and infrastructure, blocks the Similkameen river, a tributary of the Okanogan River, about four miles upstream of Oroville, Washington. It was built immediately upstream from Coyote’s Falls, one of the most important Indigenous cultural sites in the region.

For over a century, the Enloe Dam has prevented endangered spring Chinook and summer steelhead from reaching an astounding 1,520 miles of high-quality coldwater habitat in northern Washington and southern British Columbia. Both species have been completely extirpated from the vast majority of the watershed as a result.

The Enloe Dam hasn’t produced power since 1958, and the Washington Department of Ecology has designated the aging structure as a “significant hazard potential.” As the dam’s owners, the rural ratepayers in the Okanogan PUD incur ongoing costs for safety upgrades, annual maintenance and exposure to liability for a structure that hasn’t produced income or provided electricity for nearly 70 years.

Benefits of dam removal

Upper Columbia River salmon and steelhead populations have declined steadily over the past century, and conditions in the Okanogan River are especially dire, with steelhead returns consistently below 50% of recovery goals and spring Chinook salmon having gone extinct. (The Confederated Tribes of the Colville Reservation are leading an effort to reintroduce spring Chinook.)

Climate models predict that most of the Okanogan’s limited existing habitat will become unsuitable for both species within the next 15 years. Removing Enloe Dam to reconnect 1,520 miles of intact coldwater habitat in the Similkameen basin is likely the best chance at survival for Okanogan River steelhead and salmon.

Dam removal also presents a unique opportunity for the Okanogan PUD and its ratepayers to shed existing liability and secure significant partner cost-share to remove their dam.

TU’s Feasibility Study finds that removing Enloe Dam could save the Okanogan PUD up to $52 million in avoided costs over the next 50 years, create 260 project-related jobs during the five-year dam removal project, and generate up to $2.2 billion in non-market benefits to Washington State (mostly from restored fisheries).

Coyote’s Falls is a historically important gathering and fishing location for regional tribes and First Nations. The construction of Enloe Dam ended the salmon runs and installed infrastructure across the area around the falls. Removing the dam will return this sacred site to its natural condition and restore valuable cultural and first foods resources.

Next steps

The Enloe Dam Removal Feasibility Study is a critical step in the long process considering a potential dam removal project, but it alone isn’t a final determination if the project will eventually proceed or not. Additional work is necessary to evaluate the study’s results to determine the best path forward for the dam’s owners, regional communities and tribes, the Similkameen’s salmon and steelhead, and Washington State.

In the next phase of work, TU and our partners will identify and recommend a potential dam removal approach from the options described in the study. We will work with engineers to develop a project design to 30% of completion, develop a plan to manage the sediment impounded behind the dam, identify the permitting pathway for a project of this scale, further refine estimates of project costs, and develop a comprehensive insurance liability program similar to what was used when the Klamath Dams were removed.

As the process moves forward, the partners will host opportunities for the public to learn more about the potential to remove the Enloe Dam and how to participate in the process. These public meetings, and other progress updates, will be announced online at: www.enloefeasibilityassessment.com/

Photos by Steven Gnam.