When Trout Unlimited crews and contractors dive into a construction project, they move fast. Often, it takes just a week or two of construction to complete the work.

Getting to construction can be a longer haul.

It was more than a decade ago when Chad Kotke, a stream restoration specialist on TU’s Great Lakes team, learned of a problem on a small stream in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula.

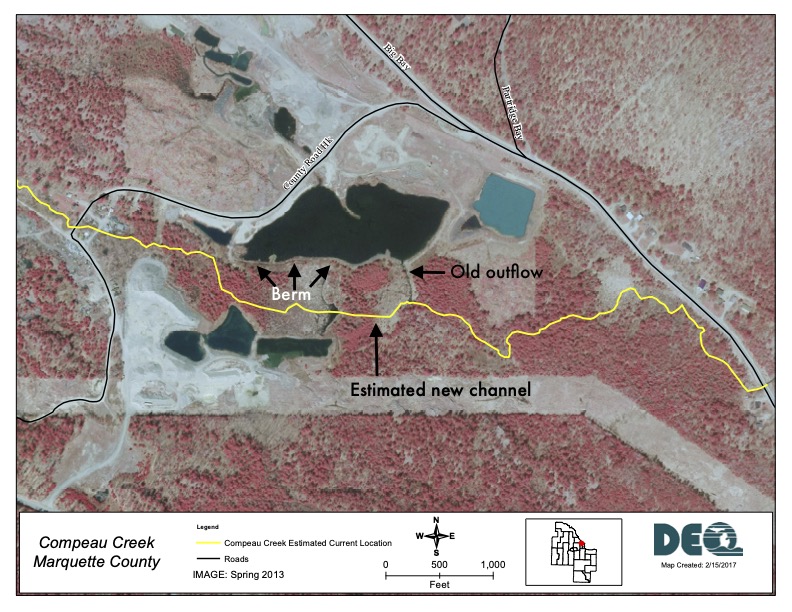

“My friend Mitch Koetje, who works at the Michigan Department of Environment, Great Lakes, and Energy (EGLE), brought this one forward,” Kotke said. “Compeau Creek, a coldwater stream, had jumped its banks and was running down a road and into a water-filled gravel pit (gravel mine).”

From trout to pike

The impact on water temperatures was significant.

“Upstream, the water was 50 degrees, and the stream had tons of brook trout,” Kotke said. “Downstream from the pond, it was 70 degrees with pike, largemouth bass and perch.”

Identifying the problem was relatively easy. Getting the project to construction took until 2024, when EGLE was able to secure funding through the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation’s Save Our Great Lakes program and Marquette Township.

TU’s Sarah Topp helped secure and manage the project’s grant funding.

“Mitch and I have a long history. We went to school together at Grand Valley State University 25-ish years ago, and we worked together at EGLE for 15 years before I came to TU,” Kotke said. “He came to me and said, ‘I’m going to be able to get some money for Compeau Creek. Would you be interested in designing it for me?’

“I was like, ‘Heck yeah!’”

Getting to work

Kotke’s design was minimalistic and focused on process-based restoration. His idea was to build a berm to block the stream’s route into the gravel pit. The berm included several layers of material, including gravel.

“Using that course gravel would allow for groundwater flow subsurface, creating a wetland on the outside of the berm,” Kotke said.

Re-routed, the stream would flow through a cedar swamp and a historic beaver dam complex before rejoining the channel below the pond.

The property’s owner is a contractor, A. Lindberg & Sons, and they handled the construction work.

“On August 26, 2024, we were able to flip the stream over,” Kotke said. “We had complete reconnection of the wetlands and the stream.”

TU installed an EnviroDIY Monitoring Station downstream with the help of Middle Island Point Campers Association to record water temperatures prior to construction.

With the help of Middle Island Point Campers Association, TU installed an EnviroDIY Monitoring Station to record water temperatures below the project site.

“There was an almost-immediate 12 degree drop in temperatures,” Kotke said.

Holding strong

A year later, that impact remains with summer temperatures staying below 70 degrees, even on 90-degree days, and initial fish sampling in 2025 showing many brook trout downstream of the reconnection project.

An added bonus is that the project has reconnected the upstream section of the creek to Lake Superior two miles below the site.

Kotke said it was satisfying to see the project come to fruition after so many years.

“Back when Mitch and I were both at EGLE, we weren’t able to get it done,” he said. “But then I’m over here at TU, Mitch is still there at EGLE and he comes up with the money and he knows I can do the design. And we got it done.

“It came full circle.”