By Jacob A. Fetterman

When I decided to change my major toward the end of my freshman year at Lock Haven University, I had no idea about the journey to follow. I was looking for a career that would allow me to positively impact the natural world I grew up admiring.

Five-and-a-half years later, it is safe to say that I am well on my way to fulfilling this career aspiration.

Through my time at Lock Haven, I grew an appreciation for the possibilities there are to conserve fisheries and study the interactions between a stream, its inhabitants, and the surrounding terrestrial ecosystem.

I was fortunate to enough to intern at the local conservation district and Trout Unlimited between my sophomore and junior years, respectively.

Assessing streams for wild trout populations, monitoring water quality and temperatures, and measuring the effectiveness of stream restoration/reconnection projects convinced me that the work of Trout Unlimited was exactly what I was searching for as an unsure freshman just two years earlier.

As the job world goes, following graduation, I took an opportunity to work as a fisheries biologist for the Bureau of Land Management in Idaho, and shortly thereafter, a graduate position in fisheries management at Louisiana State University.

My desire to contribute to the great work of Trout Unlimited persisted, and I was fortunate enough to be offered a position to work as the Battenkill River Watershed Technician this summer.

A properly functioning trout stream is defined by more than simply cold, clean water. Geology, soils, land use, riparian vegetation, in-stream habitat, non-embedded stream beds, and longitudinal connectivity are several other critical components.

They contribute to the sustenance of a properly functioning watershed by supporting natural stream function which, in turn, provides the diversity of habitats to support aquatic organisms — specifically trout! — at each life history stage, from embryo to mature adult.

Thus, the objective of my work has been to gather baseline data on these variables throughout the watershed. Once compiled and analyzed, these data can be utilized to prioritize and facilitate future restoration work.

Collecting such a wealth of data for an entire watershed may sound like a tall task. Well, that’s because it is.

Thankfully, our team of Tracy Brown, John Braico and me selected a rapid assessment methodology to obtain a glimpse of the whole watershed before focusing on the main stem of the Battenkill River and one tributary (Camden Creek) with more in-depth analyses.

The broad-scale assessments involved reviewing publicly available data to indicate which of the previously mentioned components of proper stream function are limiting the potential of each smaller sub-watershed to contribute to a healthy and connected Battenkill watershed. Following field verifications, we now have a snapshot into areas where restoration work could be pursued with greatest cost-effectiveness.

Our assessment of the Battenkill River itself was extremely informative. The best laid plan — to float the river from Arlington, Vt., to Greenwich, N.Y. — was halted on the first day when our Radisson canoe stuck like glue to every rock in a riffle.

That didn’t stop us, though. We walked the first eight of 20 reaches before successfully resuming a float study in a two-person inflatable kayak.

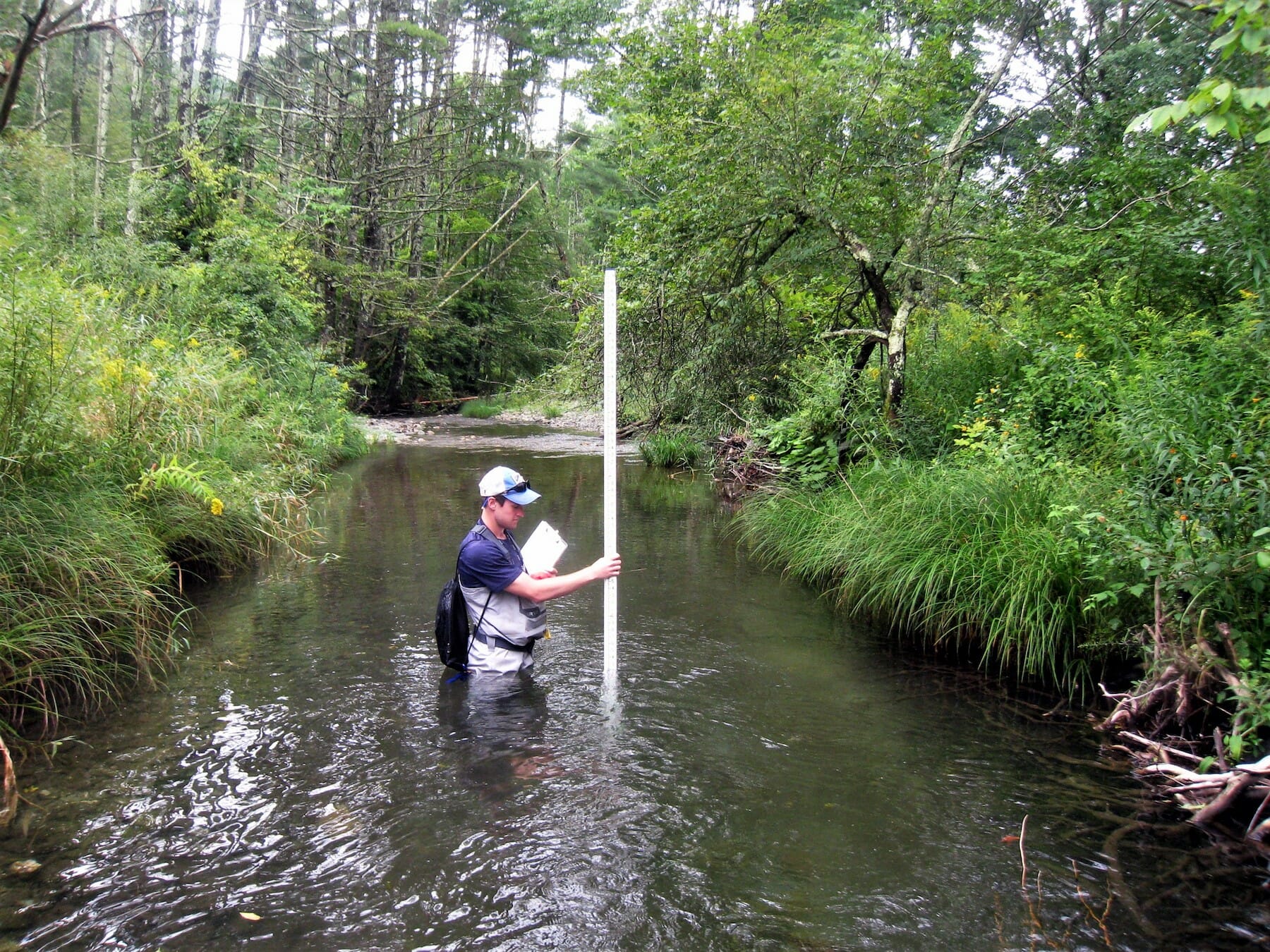

During these walks and floats we recorded river dimensions — width, depth, riffle length, and pool to pool spacing to name a few. These measurements can be compared to the expected ratios and dimensions if the river were in a pristine state.

Other critical data collected were large woody debris indexes and percentage of canopy cover.

Large wood provides critical refugia for trout from high flow velocities and predators, and provides great habitat for a trout’s favorite snack, aquatic insects.

It became apparently clear as we floated that areas where the river was farthest from its optimal dimensions (typically over-wide) were drastically lacking in adequate habitat and canopy cover to sustain a healthy wild trout population.

For Camden Creek, we walked much of its length in New York, provided landowner permission was granted, recording the same data as on the main river.

Areas of instability on the main stem and Camden Creek were most apparent through eroding stream banks and large areas of deposition. Future projects can focus on such areas to re-establish the systems connectivity to a floodplain, and in doing so, stabilize eroding banks, create habitat diversity, and reduce downstream sedimentation that is particularly harmful to trout spawning success.

We are hopeful that this information, combined with the immense local support for the recreational opportunities the watershed has to offer, will engender several years of such projects to ensure the watershed’s health and fishing opportunities are benefited in perpetuity.

I truly could not be happier with my experiences here. The Battenkill watershed is a beautiful system with many people who appreciate the numerous opportunities it has to offer. As someone who has lived in various places for short amounts of time, this is the first place where I have felt as though a community of people, regardless of background, is coming together to support the watershed that contributes so significantly to the gorgeous area they call home.