An Arctic grayling from Alaska. Gabby Mordini photo.

Western Native Trout Challenge: Arctic grayling

Editor’s note: Daniel Ritz is fishing across the Western United States this summer in an attempt to accomplish the Master Caster class of the Western Native Trout Challenge. He will attempt to land each of the 20 native trout species in their historical ranges of the 12 states in the West. You can follow Ritz as he travels across the West by following Trout Unlimited, Orvis, Western Native Trout Challenge and Montana Fly Company on social media using the #WesternTroutChallenge.

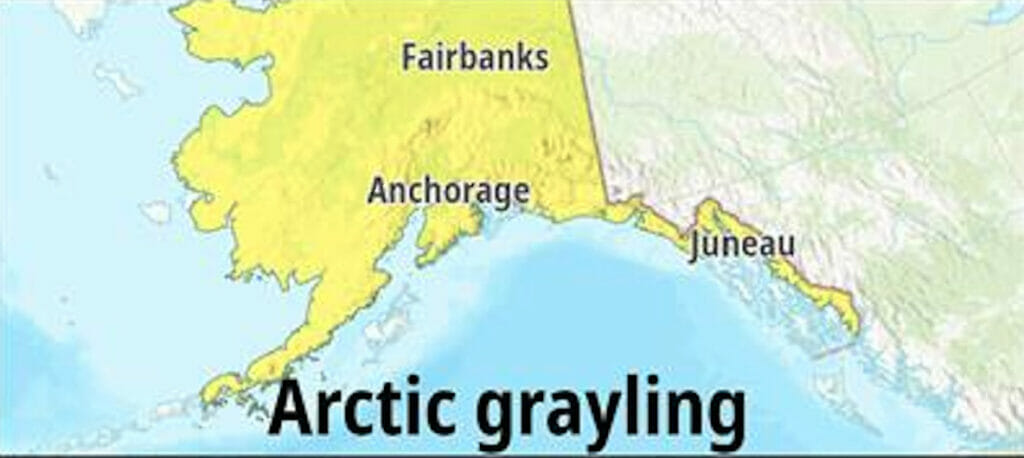

Early in our first planning conversation, Oliver Ancans, president of the Fairbanks Chapter of Trout Unlimited, asked me what species I was most looking forward to pursuing.

“Arctic grayling,” I responded without batting an eye. “I’ve never even seen one, let alone fished for them before. It’ll signify just how far from home I am on this trip.”

“Oh, don’t worry about getting grayling,” Ancans laughed. “You’ll get so many, you’ll get tired of catching them up here.”

For the remainder of the conversation he talked about lake trout. More on that later.

The first week of June, I flew from Juneau to Fairbanks where Ancans picked me up from a local brewery. We had planned to spend that evening setting ourselves up with supplies before heading to a Tanana River tributary outside of Delta Junction the next morning.

In what proved to be a trend, Ancans, who is on active duty in the Air Force and scheduled to be deployed to Kuwait later this summer, decided to move the schedule forward so we could get a bit more fishing in.

“Let’s get outta here,” Ancans said as the town of North Pole, Alaska, passed by the passenger side window.

Only hours later Ancans and I were tromping through what could only loosely be called a “trail” and crossing the river multiple times as we began our pursuit of not just Arctic grayling, but true trophy grayling.

“How could you ever get tired of this?” I asked Ancans. This was the dream.

Often, he would just smile, oozing confidence that the answer would reveal itself.

Arriving at a beautiful mint-colored hole, the sun, now at our backs and low in the sky, revealed a series of large grayling setting deep in a soft current. Watching for a few minutes, they seemed to be feeding, but staying down in the water column.

I asked Ancans what he was tying on, and he showed me a tiny blue-winged olive dry that looked as if it had been through a paper shredder.

“Dry fly? But… nothing’s rising?” I questioned.

Ancans thought this was unusual but assured me not to worry.

“Yeah, usually they’re rising all over the place,” he said.

I proceeded to tie on a personal favorite dry-dropper combination: an enormous Amy’s ant the size of a small beach ball with a small bead head hare’s ear nymph with an orange hotspot. No more than a minute passed before a strong tug came upon the line.

Arctic grayling, known to go rigid when overpowered, will give one heck of a fight on light tackle. Like their southern neighbors, Dolly Varden, there seems to be no quit in an Arctic grayling. This first fish, a fool for the orange hotspot nymph, truly gave me a run for the money. Now at hand, I could see the fish’s body was as tall as the palm of my hand, equally round with a fan fin on top as tall as my fingers. The edges of the fan were deep shades of red shifting to a sky-like blue-gray.

After the usual high five, “What’d you get it on and let’s get some more” hoo-rah and self congratulation with Ancans, I took a second to reflect on what just happened.

“How could you ever get tired of this?,” I exclaimed to Ancans. “I could do this all day!”

Distracting me, though, was the pod of 8 to 10 grayling that had gathered slightly behind me. As if they didn’t think I could see them, grayling swam nonchalantly around picking up the aquatic bugs I shook loose with my footstep.

“It’s crazy, there are so many of them. They just gather behind you,” I remember saying as I cast out into the dropoff ahead of me. We fished for hours, bringing a dozen or more 18 to 20-inch grayling to hand before calling it quits for the evening.

We took a break from the grayling and after a couple days of hunting lake trout in the sleet, sideways rain and constant wind in the Alaska Range, we returned to the Tanana River tributary where we had so much initial success.

Ancans took us deep in the woods in order to keep our path out of sight of curious eyes, to another hole down yet another what I affectionately call “Alaskan Trails” — in other words any slim gap no more than 18-inches in between two birch trees.

We finally arrived at a breathtaking 400-yard long gravel bar dropoff hole, where one after another we picked off sizable grayling far beyond the view of the weekend warriors. I was personally overjoyed to hook and release a slightly less than average size post spawn grayling, so dark it appeared dark purple, if not black.

After releasing that particular fish, I remember scanning the river.

Behind me, the usual swirling pod of 10 to 12 grayling had gathered. However, one of them stood out beyond the rest. This wasn’t a bigger than usual grayling. It was the biggest grayling I had seen yet — easily over 20 inches.

I didn’t exactly cast to it as much as I redirected my already sunken fly in its direction and as dependable as clockwork, the fish rose, leapt up and over, and then down mouth first onto my oversized dry fly.

I was immediately taken with a sense of guilt. I do my best not to anthropomorphize my fishing experiences, but I admit I felt I had betrayed the grayling’s sense of trust.

I immediately let the fish go, letting the barbless hook slip from it’s mouth without touching it. Standing in the river for a long moment, sorting through what I was feeling, I realized dangling a fly in front of a trailing fish isn’t a macro-level issue that is likely to bring population crashes, but it is evidence of a state of mind that will.

“They’re smooth-brains, but we love ‘em,”one of Ancan’s buddies had said, speaking about grayling, a few days earlier. He said it in the same tone an older brother uses with friends who need to remember that while he can speak ill of his sibling, others absolutely cannot.

I had come in pursuit of Arctic grayling expecting an experience that would exemplify my traveling more than 2,500 miles from home. I had for some reason expected my experience with Arctic grayling to shock me into some sort of twisted sense of ego-driven pride fueled by exotic destinations.

Instead, it was the backhanded loving tone Ancans and his peers spoke of grayling that revealed something truly exotic.

As the saying goes, we often don’t give flowers while people can still smell them. We don’t appreciate the things that are beautiful, good, and simple while we can. Often, we wait until it’s too late, until something needs to be saved to consider it important.

The Western Native Trout Initiative’s Arctic Grayling Species Status Review reads like the kind of a report we all would love to see for other species that are considered more at risk.

It’s possible that a number of habitats could be impacted or developed on, many more grayling could be harvested either for sport or subsistence, in Alaska before the species were at risk of population decline.

After dangling that fly for that trailing fish, I thought of the non-existent grayling populations in Michigan and fledgling populations in southwest Montana. I thought about how I was disappointed in myself when I felt I had unfairly and unnecessarily taken advantage of a trusting member of my community.

The exotic lesson I learned from Arctic grayling was that just because you can do something doesn’t mean that you should.

Self control without mandate, before the need for regulation, could go a long way in many aspects of our culture.

I had come more than 2,500 miles longing to experience my most exotic fish to-date. When I did, the experience taught me it was ok to take what you need, not everything you can.

With my train coming to the station early the next morning, Ancans asked me how I felt.

‘I think I’ve had enough…” I said, realizing that Ancans was right. “For now.”

I wasn’t tired of catching grayling, I just didn’t need any more at the moment.