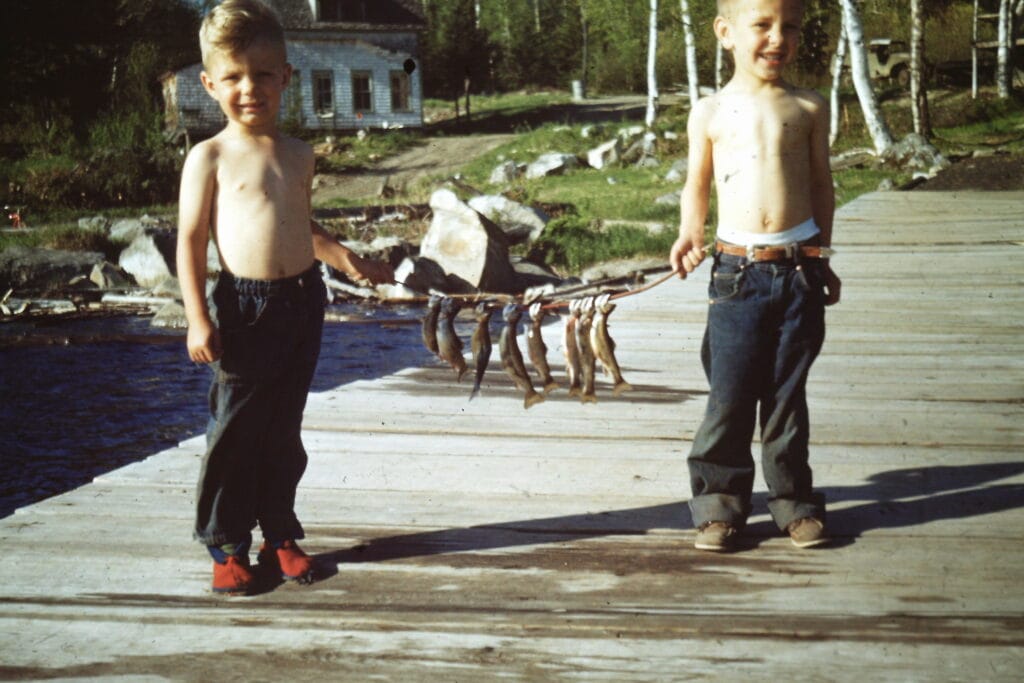

Steve Brooke doesn’t actually remember his “first fish.” But there is a memento of that moment, a photo of a not-yet-year-old Brooke sitting on his mom’s lap, her holding a pretty cutthroat trout caught near the family’s home in Colorado Springs.

Nearly 80 years later that photo remains a powerful image that predicted a life lived outdoors, one appreciative of nature’s wonders and one dedicated to protecting those wonders.

Just keep working hard

A long-time resident of Farmingdale, Maine, Brooke has been a tireless advocate for the state’s coldwater resources, his passion for trout and Atlantic salmon driving his efforts to work — alongside many others — toward their protection. He’s seen some defeats, and many victories.

“I think the key is to approach your life strategically and with forethought, and to engage as many others as you can so you don’t have to do it all by yourself,” Brooke said. “It doesn’t really matter who gets credit for something as long as the job gets done. Just keep working very hard along the way.”

Brooke’s father was a military man and was in Japan when Brooke was born. Before he was a year old, the family moved to the Northeast, settling in the Boston suburbs. The family had a cottage in Maine, and that’s where Brooke spent his summers.

“I played in the swamps and in the salt marshes, on the beach and in the tide pools,” recalled Brooke, who just celebrated his 80th birthday. “In my generation, when you grew up in Maine, you were outside all the time.”

Father as mentor from one generation to the next

“My dad was an avid cross-country skier, a fly fisherman and hunter of waterfowl, upland birds and deer,” Brooke remembered. “I spent a lot of time with him outdoors before high school, which is when my life got really busy.”

Brooke attended an Episcopal boarding school in New Hampshire, the rigorous academics cutting into his fun time but preparing him well for his next stop at Colby College, a small-but-prestigious school in Waterville, Maine. The school is near the Kennebec River, and less than a mile from one of many dams that block fish from upstream migrations. Brooke didn’t know at the time how strong his ties to the Kennebec would become.

After grad school in New York, Brooke returned to Maine, where he worked for 17 years at the State Museum in Augusta as a conservator. A major focus of his work was preservation of marine archeological artifacts from shipwrecks, of which there are plenty in Maine’s coastal waters. Then came 10 years of running his own business doing conservation work for individuals and museums throughout the Northeast. After a year with American Rivers he returned to public service, finishing his career as a senior planner for the Maine State Planning Office.

In the 1980s, Brooke became an active member of TU’s Kennebec Valley chapter.

“I really joined so I could take my son and daughter out on some of the field work the chapter was doing,” he said. “For example, we did a lot of fencing along the Sheepscot River to keep cattle out of the river.”

As a chapter leader, Brooke also joined the movement calling for the removal of Edwards Dam on the Kennebec. Built in the 19th century just above where the river becomes tidal, Edwards Dam was a converted mill dam that produced very little electricity while blocking upstream fish passage.

“We worked closely with the Maine Department of Marine Resources, building the case over probably 10 or 12 years about the damage this mid 19th century dam was doing by blocking sea run fish,” said Brooke, who was among many who were thrilled when the dam came down in 1999. “One of the great successes was the impact that removal had on shortnose and Atlantic sturgeon. They are great creatures, literally dinosaurs that live with us today, and their populations have exploded.”

One dam down and more to go

Brooke knew there was much more to do. Representing his TU chapter, the Kennebec Coalition, a consortium of conservation organizations, Brooke worked for years alongside other river advocates as they turned their attention to the next four dams on the river.

In September, the Nature Conservancy announced that it reached an agreement with the dams’ owner, power company Brookfield Renewables, to purchase the four dams. Within the year, a new nonprofit — The Kennebec River Restoration Trust — will be formed to take ownership of the dams, overseeing operation of the hydroelectric facilities while the dams are eventually decommissioned and removed.

Keith Curley, TU’s vice president for conservation, has worked with Brooke often over the years.

“Steve has all the hallmarks of a great conservationist, including the faith that we can prevail—sometimes against long odds—in our efforts to recover ecosystems, and the persistence to keep working as long as it takes to succeed.” Curley said.

Among the many species that can’t migrate past those dams, endangered Atlantic salmon garner a lot of attention. Brooke points out that salmon are part of a much larger system.

“Bringing life back to the Kennebec is not just for individual species,” he said. “It’s for the entire ecosystem.”

Never give up

Even after the big news about the lower Kennebec dams, Brooke plans to keep fighting for Maine ecosystems. He recently took on another effort targeting dams on a Kennebec tributary. And while he can’t ski anymore, he remains an avid brook trout angler and hiker, enjoying walks in the woods with his wife, a Maine master Naturalist.

While looking back on a life well-lived, he embraces efforts yet to come.

“I learned how to pick battles carefully,” he reflected. “You don’t latch on to every single problem. You’ve got to kind of have a gut feeling of what you have, and what gives you the potential for success.

“And then you never give up.”

Steve Brooke is a brook trout fanatic, and there is arguably no better place in the U.S. to chase brookies than Maine.

“I especially love to fish for them in the North Woods,” Brooke said. “I don’t care if it’s lakes, ponds or streams, brook trout inhabit all of them here, and they’re all wild.”

The variety of habitats create a variety of fishing opportunities.

Maine has more than 22,000 miles of brook trout streams, from small blue lines brimming with brookies eager to wallop a gaudy dry fly to big rivers where 20-inch fish don’t merit a second glance.

Ponds offer brook trout fishing in a unique setting. Many are remote, reachable only after a tough hike. You can hope to find a canoe on the shore (and often will, though it might be locked to a tree) or you can hedge your bets and carry in a float tube. Troll a streamer or cast a dry to dimpling fish and hold on.

The same free-flowing rivers that sustain trout and salmon bring clean water into our homes, give life to vibrant communities and feed a passion for angling and the outdoors.

But today our fisheries and rivers face enormous challenges. At Trout Unlimited, we are doing something about it, and we need your help. Sign up to be a champion for the rivers and fish we all love and help us unlock the unlimited power of conservation.