The plan, as so many good ones do, started over a beer.

Well, several beers.

“We’re going to be at Hunting Creek next Wednesday with the EPA,” my friend Jason Hill said, a couple hours into another friend’s birthday bash at the Starr Hill Pilot Brewery in Roanoke, Va. “You should come.”

“Absolutely,” I said, not bothering to look at my calendar to see what I would be blowing off to go spend a day with a bunch of water-testing, fish-squeezing, data-analyzing nerds. “Do you need to clear it with anyone?”

Hill grabbed his phone, typed a quick text and waited. Twenty seconds later he had the answer.

“You’re good.”

Hill works for Virginia’s Department of Environmental Quality, and has been spending some time this summer with the EPA on the National River and Stream Assessment, for which EPA selects 1,000 random, wadable streams and 1,000 boatable rivers to sample over a two-year period.

The NRSA launched in 2008/2009, with subsequent studies every five years. So, this is the fourth iteration.

By analyzing data collected at each site, EPA will be able to statistically estimate the percentage of streams with problems with indicators such as dissolved oxygen, habitat, and benthic diatom, macroinvertebrate and fish communities.

The mission was a double-dipper as Hill and DEQ counterpart Brett Stern were also collecting info for the Regional Monitoring Network, which has been looking at coldwater resources from Georgia to Maine since 2014.

Trout Unlimited does some of this kind of monitoring work, too. We rely not only on staffers but also an army of volunteers trained in various testing protocols. TU also utilizes technology such as remote stations such as Mayfly Data Loggers to collect information.

All this information, be it basic data collected by volunteers or extremely detailed information collected by professionals, helps us understand what’s happening on our streams and then helps inform those responsible for water resources how to manage those resources.

In the case of the National River and Stream Assessment and the Regional Monitoring Network, collecting reams of data is no minor undertaking.

“I don’t think I’ve ever seen a Suburban packed with so much gear,” Hill laughed as we pulled up next to one of the EPA rigs.

The back two-thirds of the huge SUV was packed to the ceiling with scientific gear, including surveying and eDNA-collecting equipment, electrofishing backpacks, nets, waders, boots, sample bottles and coolers. A trailer behind the Suburban carried a raft and two kayaks.

I had to laugh thinking about the difference between this operation and my foray into sampling a couple springs ago with the Virginia Trout Stream Sensitivity Study. (My mission: Collect two water samples in small bottles; put samples in a cooler; move on to the next site.)

Hill, Stern and the EPA crew, most of whom are based at the agency’s office in Wheeling, W.Va., quickly went to work formulating a plan for the day. Within 30 minutes, the work was underway.

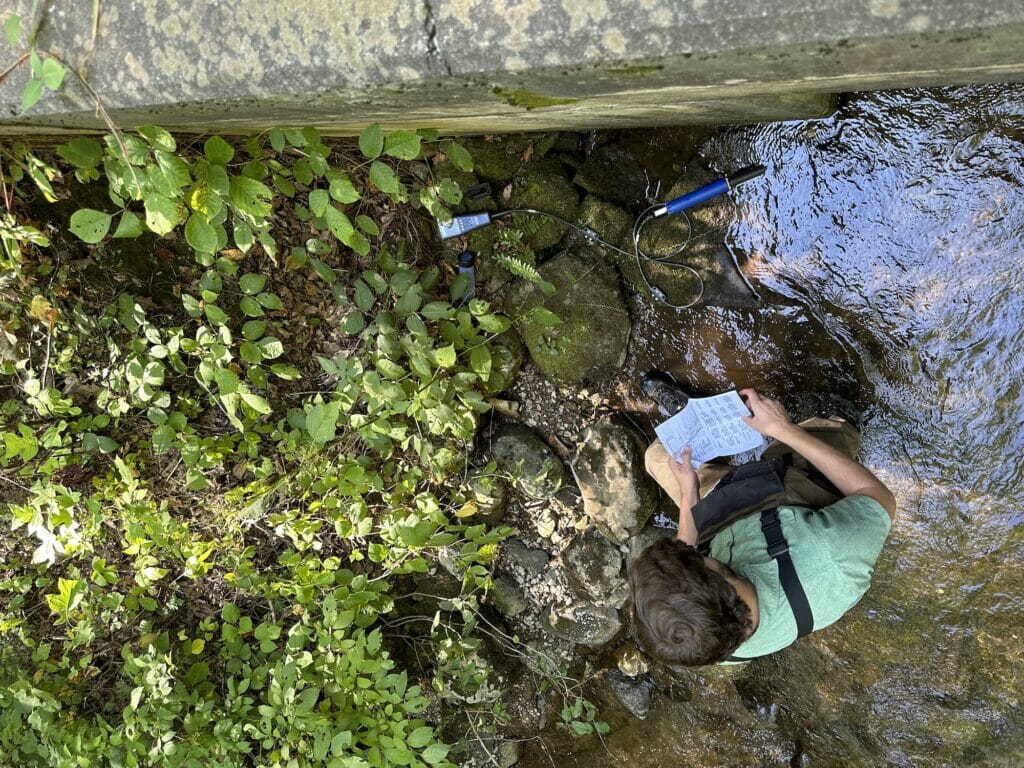

Teams marked off a 200-meter stretch of the creek into segments, surveying the stream’s elevation drop, recording streamside vegetation and riparian tree cover, running water through a high-tech eDNA scrubber machine, collecting stream bugs in nets and scraping coating off the bottoms of rocks into sample jars.

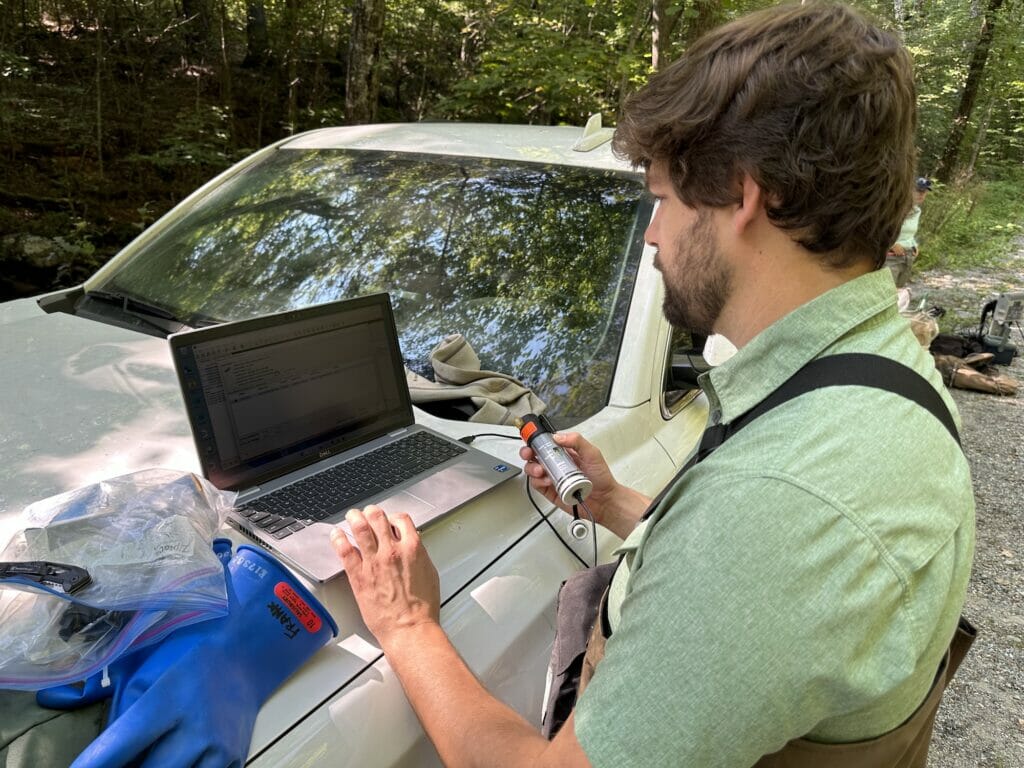

Stern pulled data from two temperature monitors — one on a tree and another in the stream — and downloaded it to his laptop.

Then he, EPA biologist Lou Reynolds and I started working our way up the creek with electrofishing gear. We collected brook trout, sculpins and a lot of fat black-nosed dace.

It took all day, which was actually a relief for the crew after the previous day’s work in boats on the Cowpasture River, an effort that didn’t end until 8 p.m.

Watching the professionals was impressive and encouraging. These folks not only know what they are doing, they care.

As the day’s work wrapped up, it dawned on me that this narrative was missing one key element: resolution.

Collecting data at a single site is interesting, but it’s a tiny snapshot. It was fun to see brookies, sculpin and dace swimming in our collection bucket. But those fish were a tiny data point, one that needs many other data points over time to really mean anything.

While surveys and sampling can relatively quickly suss out acute problems, more subtle trends often can’t be identified without decades’ worth of information, all of which must be carefully analyzed.

“I’m not a statistician,” Hill told me. “But it’s my understanding that we really need 20 to 30 years’ worth of information to analyze, so we’re still really early in this process.”

Conservation work isn’t for those who need instant gratification. It’s a long game and we should be grateful for those who do the work knowing that they may well be long retired before that work bears fruit.