By Jeff Reardon

I’m following a green state truck through Freeport, a coastal Maine town best known as the home of L.L. Bean, horrendous summer traffic and outlet malls, when the truck slams to a stop on a busy road. I know this isn’t the right spot, but I check my GPS anyway. No, it’s not the brook we’re looking for. It’s not even on my map.

“I want to check this one,” says Maine Department of Inland Fisheries and Wildlife biologist Jim Pellerin. “I think we have an application for work on this culvert.”

Jim and his partner Brian Lewis (above) grab their gear — a net, a plastic bucket, and a backpack electrofishing unit, and scramble down over the rip rap to the “stream.”

It’s not much to look at — a plunge pool dug by a small waterfall dropping out of the culvert under the road. Downstream of that is sand and gravel for 10 yards or so, then another pool, then another dry stretch, then another small pool. I head for the cooler in the back of the truck to get a water bottle. It’s been a long day and I figure I can rehydrate in the 10 minutes it will take Jim and Brian to confirm there are no trout in this trickle.

I sit on the tailgate with Steve Dewick, a volunteer from Maine’s Merrymeeting Bay Chapter of TU. He’s the reason we’re here.

Steve and a handful of other MMBTU volunteers spent the spring fishing the small brook this intermittent tributary flows into, and they caught some brook trout — about 2 miles and four impassable culverts downstream. It’s part of a an “angler science” effort by TU, Maine Audubon, the Sea Run Brook Trout Coalition and the Maine DIFW to document trout populations in coastal streams that might support “salters,” brook trout that migrate downstream to salt water.

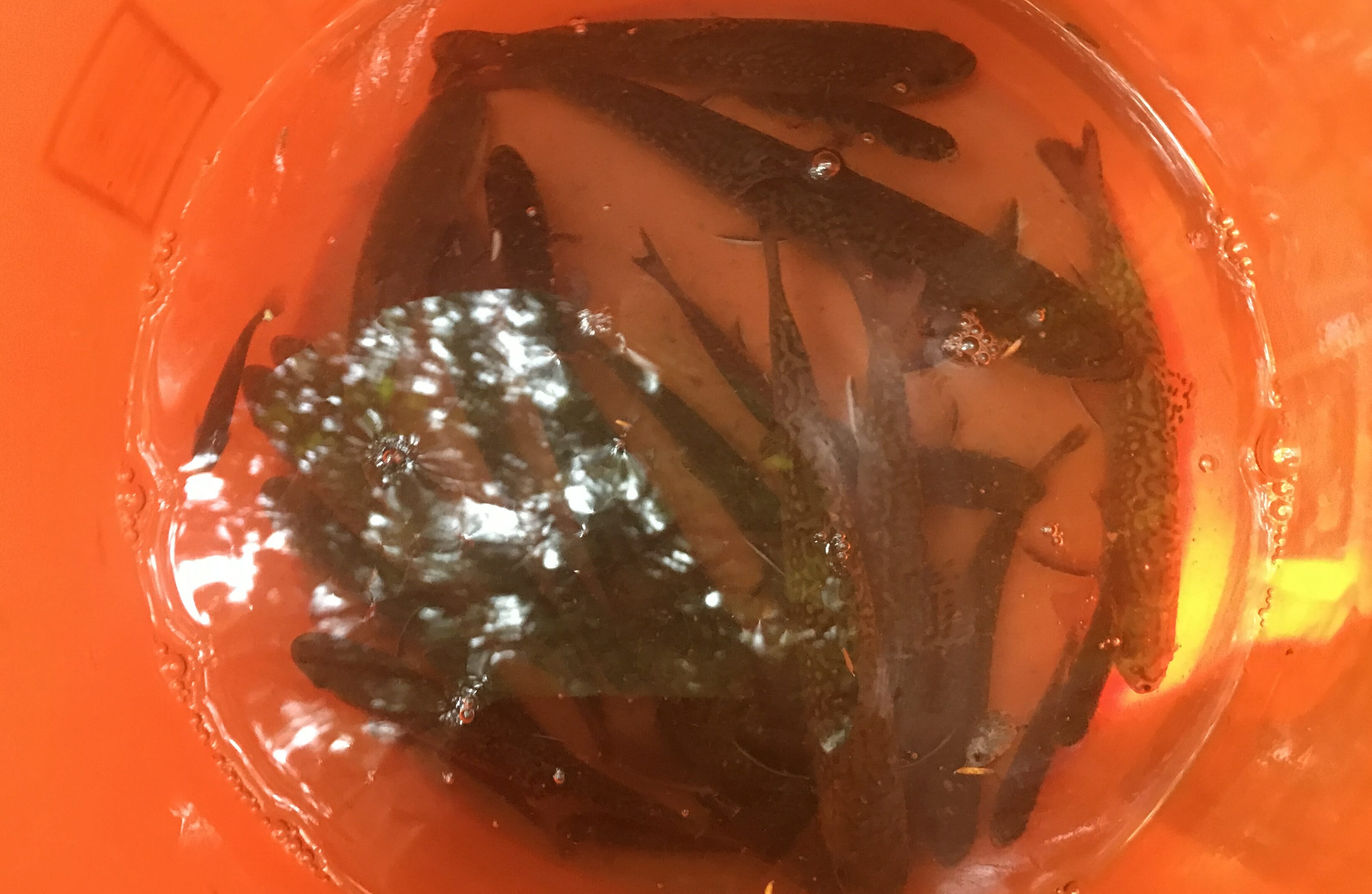

Earlier in the day, the four of us had confirmed that the trout volunteer anglers found back in April and May are still there — and the several dozen brook trout we netted were anesthetized, measured, weighed and carefully released. It’s the first time Maine DIFW has looked at this stream in more than 30 years. When they were here back in the 1980s no trout were found.

Steve and I are feeling pretty good — TU’s volunteer efforts documenting a “new” wild brook trout population a half-mile from the LL Bean parking lot complex — when we’re interrupted by a shout.

“You’re going to want to see this!”

Jim is at the bottom of the slope with a big grin.

“You got a brook trout?” I ask.

“Yep. We got them in every pool,” he answers.

So we add that stream to our list — along with two other unnamed tributaries we fish that day, and another Freeport stream and two of its tributaries where we find trout a week later.

Slowly, stream-by-stream and culvert-by-culvert, we’re putting brook trout on the map, giving Jim and Brian the information they need to do their job. The next time they process an application for a culvert on this stream, they can ask for improved fish passage. And, over time, we’ll reconnect this little stream to the bigger brook, and to the salt marsh down below, and let salter brook trout swim up here to spawn.

Small streams matter.

Jeff Reardon is the staff lead for Trout Unlimited in Maine. He’s an avid angler who often can be found pursuing native brook trout in Maine’s streams and ponds.