In our last post we explored how TU’s work on the ground is helping to change the conversation around water storage and how the use of “natural storage” increases water security for agriculture, people, and the environment. In this post, we’ll talk about how TU works with federal agencies to ensure that the projects they authorize and fund include projects that provide environmental uplift, increase water security and help answer the perpetual question of how best to use the West’s water resources in the twenty-first century.

Each installment of Western Water 101 will be accompanied by a podcast, released weekly. Find the fourth episode below, and subscribe to get each new episode as it’s released.

TU staff work with federal agencies to make sure programs and funding respond to the West’s needs. In order to do this, we undertake detailed research and analysis of key programs run by federal agencies to see how the program has performed and whether it has fulfilled its statutory purposes. TU also draws on the deep well of experience from TU staff, volunteers, ranchers, farmers, and other partners engaged in putting projects on the ground in collaboration with the federal agencies. From this research and experience, we determine if there are agency-level or legislative changes we can advocate for to bring the greatest benefit to the West’s rivers, streams, and the communities that depend on them. We then work with agency staff, members of Congress and stakeholders to make these changes. Through this work TU has built deep relationships with the people who are engaged in these issues, and we are seen as a trusted, experienced and nonpartisan organization working for improved water management, water security, ecological health and a thriving agricultural economy in the West.

In 2009, Congress passed and President Barack Obama signed into law the SECURE Water Act. This legislation continued the conversation, begun in the late-nineteenth century, about how much water the West has and how best to use it, but in a way that modernized that conversation. It attempted to incorporate a greater number of stakeholders, a wider range of values around water and recognition of the threats posed by climate change to water supply, ecological resilience and human communities. As then-Commissioner of Reclamation Michael Connor testified about the law in 2010, it was designed “to plan for climate change and the other threats to our water supplies and take action to secure our water resources for the communities, economies and the ecosystems they support.”

Out of the SECURE Water Act grew the Bureau of Reclamation’s WaterSMART (Sustain and Manage America’s Resources for Tomorrow) program. WaterSMART today remains an important part of the Bureau of Reclamation’s work and includes a number of programs designed to work toward water security in the American West.

These include a water marketing grant program, basin studies that examine water supply and demand in western watersheds, a drought response program and support for collaborative watershed-based work, among others. The SECURE Water Act authorized these programs to do a lot of really great things, including conserving water, increasing water use efficiency, improving ecological resiliency to climate change and protecting and restoring habitat for threatened and endangered species.

Despite the legal authorization of the WaterSMART programs to undertake these actions that would increase regional water security and ecological health—and would benefit the tribes, cities, agricultural communities and recreation interests in the region as well—some of the WaterSMART programs have not yet lived up to their full potential. As an example of how TU works for agency change, we’ll look at the Water and Energy Efficiency Grants (WEEG) program, a WaterSMART program that provides grants for irrigation districts, municipal water providers, tribes, states and other eligible entities to increase their water use efficiency and/or hydropower production. Projects funded under WEEG include replacing open, unlined canals with pipes to decrease water loss through seepage and evaporation, installing remote sensors that track water use and adjust irrigation accordingly and a host of other efficiency projects.

Through in-depth research and analysis, TU has found that over the eleven years of the WEEG program, many of the agricultural infrastructure projects funded by the program have not helped to increase water security for all users nor have they focused on improving ecological health in the West, as they are legally authorized to do. Not every irrigation infrastructure project presents the potential to improve fisheries habitat or riparian areas. TU supports our western ranchers and farmers having full access to irrigation infrastructure funding. TU’s concern regarding the WEEG program’s funded projects, however, is when irrigation infrastructure projects work at cross purposes to water security for all water users. This happens when water formerly diverted but returned to the source of supply is captured through water efficiency upgrades and is used consumptively.

Congressional committees on appropriations in both houses share this concern and have voiced this in their annual report on the Senate Energy and Water Appropriations bill in 2019 and 2020. In 2019, the Senate Committee on Appropriations expressed its concern that many of the projects Reclamation funds through WEEG are agricultural irrigation projects that “may increase water scarcity at the basin scale by allowing conservation grant recipients to use conserved water for consumptive use.” In other words, instead of contributing to water security, these projects contribute to water scarcity in an already water-scarce region.

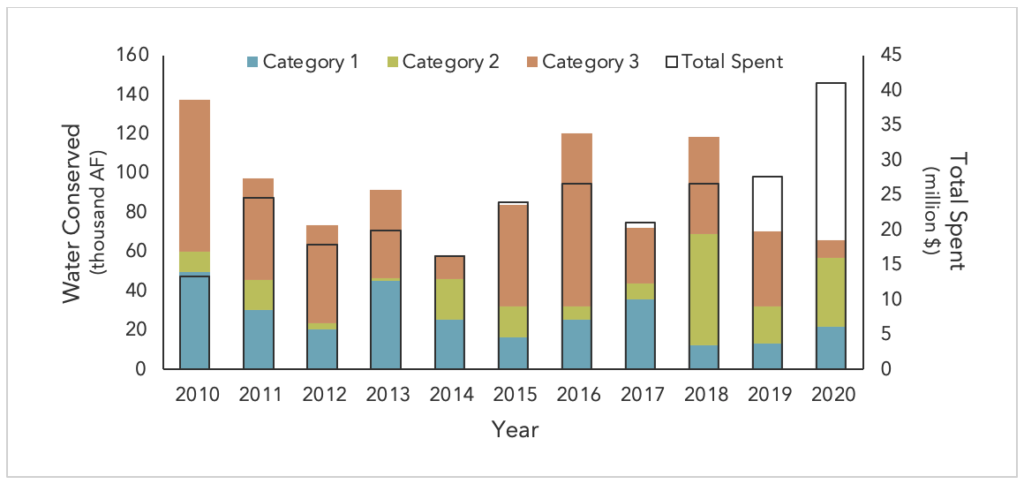

TU’s research into water conserved by WEEG projects bears out the Committees’ concerns. We sorted all projects over the life of the program (from 2010 to 2020) into three categories using the project descriptions provided by the Bureau of Reclamation based on the purpose or use to which the conserved water was put:

- Category 1: Multi-benefit projects that decrease water scarcity at the basin scale by contributing conserved water to habitat restoration, increasing instream flows, and/or decreasing diversions.

- Category 2: Projects that reduce water imports and/or reliance on water storage.

- Category 3: Projects that make conserved water available to users.

We then tracked the amount of funding versus amount of water conserved, both for the WEEG program in entirety (Graph #1) and for the three categories of projects (Graph #2).

Water Conserved by Category (af) v. Total Spend ($)

As the second graph (right) shows, the amount of water conserved by Category 1 projects has decreased over the eleven years of the program despite increased funding for WEEG as a whole. TU has expected that, over time, Category 1 projects would see higher funding levels and therefore be putting WEEG dollars to work in projects whose conserved water realizes multiple benefits for users and the environment and leads to increased basin-wide water security. However, the opposite has proven true: water conserved by Category 1 projects has decreased despite increasing funding levels. Water conserved by Category 2 and 3 projects has increased overall, and it is questionable whether those projects decrease water scarcity at the basin scale in keeping with the concerns expressed in the Senate Report.

Over the first eleven years of the program, 51% of the total conserved water went to increased consumptive use, with 501,988 acre-feet in Category 3 projects relative to the 988,694 a-f in total conserved water among all projects. In comparison, Category 2 projects accounted for 191,889 a-f, or 19%, and Category 1 projects conserved 294,807 a-f, or 30%, of total conserved water.

TU is working on ways to support more infrastructure projects that provide environmental and water security benefits—those best-in-class Category 1 projects—funded under the WEEG programs because of the remarkable ability of these projects to provide benefits for agriculture, the environment, local economies and recreation. For example, the Kittitas Reclamation District (KRD) received funding in 2018 to line 1,600 feet of the South Branch Canal which will conserve 183 acre-feet of water per year. This conserved water will be dedicated to instream flows in the upper Yakima River Basin to improve habitat for at-risk populations of salmon and steelhead.

This project received support from TU and American Rivers and is part of the larger Yakima Basin Implementation Plan, which is the result of a work group comprised of agricultural producers, conservation NGOs, the Yakama Nation, irrigation districts, and state and federal agencies. This group recognized that fish, farms, and people all need clean, fresh water to survive and thrive, and from this grew the goals of environmental conservation, enhanced fisheries, and water security. Along with the shared goals of improved habitat and fish passage, increased surface and groundwater storage, and a flexible water marketing system, the Yakima Plan intends to conserve up to 170,000 acre-feet annually through irrigation infrastructure upgrades achieved through projects like this one on the South Branch Canal. Additionally, multi-benefit projects like those undertaken by KRD provide economic stimulus through job creation in KRD’s rural communities.

TU has had recent success in supporting more multi-benefit projects and addressing the concerns of the Senate Appropriations Committee to ensure that the WEEG program effectively conserves water in a way that is beneficial for users, the environment and for basin-wide water security via legislation. TU together with a variety of partners worked to include legislative provisions in the recent omnibus legislation to take the first step towards remedying these issues. At the end of 2020, Congress passed and former President Donald Trump signed into law an omnibus bill that funds the government through the end of federal fiscal year 2021, provides pandemic relief to Americans, and includes several significant western water bills critical to TU’s work in the West. This suite of bills strengthens provisions for WEEG projects that benefit both producers and the environment.

Highlights of this programmatic expansion include the addition of:

- Natural water storage—such as the construction of Beaver Dam Analogs—as an eligible project purpose;

- Non-profit organizations, in partnership with irrigation districts, as eligible entities for funding;

- Enhanced, federal cost-share from 50 to 75 percent for multi-benefit projects, such as a project that increases water efficiency by eliminating ditch seepage in order to deliver the same amount of water for consumptive irrigation use while diverting less, accomplishing an increase of water in the source to help deliver water through natural stream channels while improving aquatic habitat;

- Increased accountability for benefits associated with irrigation efficiency projects, such as monitoring for higher streamflows or improved aquatic habitat; and

- A new Reclamation program to help fund improvements to fish passage.

This legislation will help the WEEG program fund more multi-benefit, Category 1 projects that will help address the twenty-first-century challenges of drought and water scarcity in the American West. Now that these provisions have been signed into law, TU will be advocating for their implementation by Reclamation in a way that provides increased water security for agriculture, people and the environment.

Through our research and the relationships we have built within the Bureau of Reclamation, TU is working to ensure that Reclamation’s investments in agricultural irrigation infrastructure through the WEEG program help respond to water scarcity conflicts in the American West. In doing so, we help make sure that federal agencies are providing solutions to the twenty-first century challenges facing the West through programs and projects that contribute to basin-wide water security for agriculture, people, and the fish and wildlife that call this region home.

Table of Contents

Western Water 101

- Introduction to Western Water

- Conflict to Collaboration

- TU’s On-The-Ground Projects & Natural Storage: How Flipping the System Benefits People & the Environment

- TU’s Work with Federal Agencies: How Our Research Advocates for Change in the Bureau of Reclamation

- TU’s Work for Legislative Change

- Wrap-up: The state of our hydrology today in the Colorado River Basin

- Take Action