In this final installment of the Western Water 101 series we’ll turn our attention to current events to draw together some of the topics and themes we’ve explored over the course of the series. With the extremely dry conditions throughout the West, TU’s work—from on-the-ground projects to legislative advocacy and agency collaboration—is more important than ever. The current drought crisis in the region draws together many of the themes discussed over the course of this series:

- How much water is there, especially in a climate that is increasingly drier and warmer, and how do we “best” use it?

- The movement from conflict to collaboration in twenty-first-century western water management.

- The need for twenty-first-century solutions, approaches, and infrastructure to confront the twenty-first-century challenges in the region.

We’ll focus on the Colorado River Basin to do a deeper dive on the current drought and how these themes are playing out in the watershed.

Each installment of Western Water 101 will be accompanied by a podcast, released weekly. Find the sixth episode below, and subscribe to get each new episode as it’s released.

How much water is there? Not much.

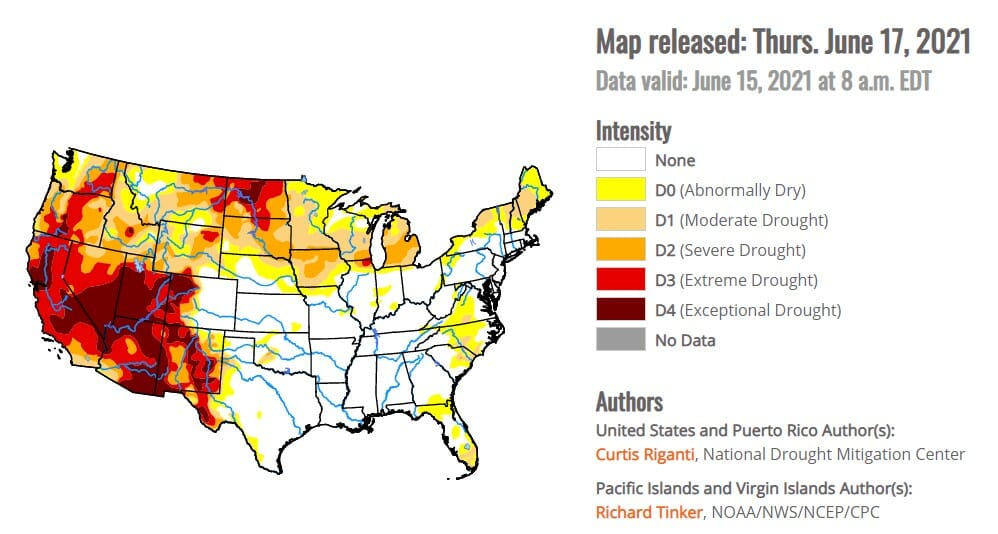

If you look at the U.S. Drought Monitor map you can see that the majority of the American West is in some level of drought, ranging from D0 (Abnormally Dry) to D4 (Exceptional Drought). These impacts are being felt across the West, from the Klamath River Basin on the border of Oregon and California to California’s Central Valley to the Colorado River Basin. Currently, 97.6% of the region is in some level of drought with almost 27% in D4, the most severe category. Despite snowpack that wasn’t all that far below the normal range over the winter, the lack of summer monsoon rains the past two years has led to extremely dry soil conditions. This means that as the snow melts the ground is soaking it up like a parched sponge, causing far below normal streamflow and inflow into reservoirs this spring and summer. The answer to how much water there is in the West—this year and for the foreseeable future—is not much. Faced with this new reality of a warmer, drier region, water managers, producers, Tribes, and conservation organizations have been working hard to answer the question of how best to use a dwindling water supply to meet the needs of people and the environment.

The Drought Monitor map shows a bullseye of extreme drought over the Colorado River Basin, the headwaters of which drain from Colorado’s Western Slope. Drought, high wildfire risk, and the potential for a shortage declaration in the Lower Colorado River Basin have all been making headlines lately. What is a shortage declaration, exactly, and what does the likelihood of a shortage declaration mean for Colorado and the Colorado River Basin?

The Colorado River Compact & Historical Context

The seven states of the Colorado River Basin—Arizona, California, Colorado, Nevada, New Mexico, Utah, and Wyoming—negotiated the Colorado River Compact in November of 1922. The states of the Upper Colorado River Basin – Colorado, New Mexico, Utah and Wyoming – were concerned that fast-growing California would lay claim to the majority of the river’s water before the smaller population of the Upper Basin states would develop a demand for the resource. Negotiated during a particularly wet period of time on the Colorado River, and ignoring evidence that the average annual flow was less than negotiators agreed upon, the Colorado River Compact requires the Upper Basin to deliver 7.5 million acre-feet of water annually on a ten-year running average to the Lower Basin, as well as half of the 1.5 million acre-foot obligation to Mexico. The understanding at the time was that the Upper Basin states would have available an approximately equal share of 7.5 million acre-feet annually. History has proven that this understanding was overly optimistic.

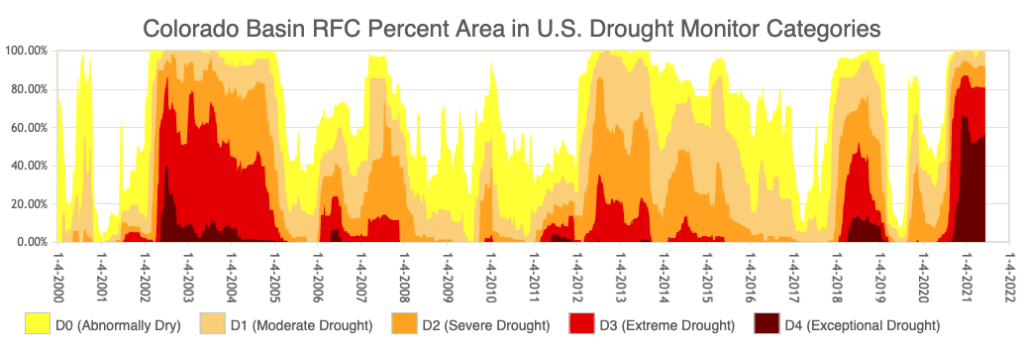

The years since the signing of the Colorado River Compact have been significantly drier than the years preceding the compact. Since the year 2000, the Colorado River Basin has been in severe drought, resulting in a precipitous decline in the amount of water stored in the Colorado’s two big reservoirs, Lake Mead and Lake Powell. Climate scientists are urging water managers and residents in the West to start thinking about the drier conditions as aridification—a long-term condition—rather than a shorter-lived drought.

Interim Guidelines & The Drought Contingency Plan

The Compact is the foundational document governing Colorado River Basin water use and development, but in the nearly century since its negotiation, a body of laws, agreements, and Supreme Court decisions has developed, known as the Law of the River and providing further governance over the Colorado River. Some of the most recent additions to the Law of the River are the 2007 Interim Guidelines and the 2019 Drought Contingency Plan(DCP), the latter of which we discussed as an example of collaboration in our second piece in this series.

The frighteningly dry hydrology at the beginning of the millennium prompted the seven Basin States to develop what are known as the Interim Guidelines: a set of criteria to determine how Lake Mead and Lake Powell would be managed based on the volume of water stored in the two reservoirs. Water users in the Basin quickly realized, as the dry years continued, that the Interim Guidelines provided a foundation for addressing water scarcity concerns but that the guidelines needed to go further to bolster reservoir storage and water supply.

In 2019, the states signed a series of agreements collectively known as the Drought Contingency Plan (DCP). The Lower Basin DCP agreement increased the amount of water states are required to conserve from the Interim Guidelines’ baseline and bumped up the elevation of Lake Mead at which those delivery reductions would begin. The Upper Basin DCP agreements created a storage “account” of 500,000 acre-feet in Lake Powell to which states could contribute water for the sole purpose of maintaining the storage volume in Lake Powell at a sufficient level such that the Upper Basin could satisfy its water delivery obligations to the Lower Basin under the Compact. Both the Interim Guidelines and the DCP represent the shift from conflict to collaboration among water users in the Basin States, and the West more broadly. This work is continuing as the Basin States, Tribes, water users, and conservation organizations are beginning the process of renegotiating the Interim Guidelines, which are set to expire in 2026, to adapt to the twenty-first-century challenge of an increasingly arid West.

The April 24-Month Projection & Shortage Projection

The Bureau of Reclamation produces 24-month forecasts throughout the year, and Colorado River reservoir operations are based on the August forecast. The August 24-month projections determine Lower Basin reservoir operations based on the elevation of Lake Mead on January 1st as projected by the August forecast.

The 24-month study released in April of this year is newsworthy because it forecasts that, for the first time, Lake Mead’s elevation will be below 1,075 feet in elevation on January 1st, the trigger point for a Tier 1 shortage declaration per the Interim Guidelines and DCP. The declaration requires Arizona and Nevada to take cuts in their Colorado River water supply, while California does not take a shortage until Lake Mead hits elevation 1045’. For Arizona and Nevada, these cuts are “planned pain,” as an Arizona water manager recently described it; the Lower Basin has been preparing for shortage declarations for years and has “mitigation water” available to fill the gaps created by the decrease in Colorado River supply.

For the Upper Basin, a shortage declaration in the Lower Basin doesn’t have any practical effect and doesn’t cut water use in any of the other Upper Basin states. It is, however, a sign of the difficult hydrological conditions the Colorado River Basin and the West more broadly are facing. If dry conditions continue into future years, and the Upper Basin states fail to deliver 7.5 million acre-feet of water per year to the lower basin on a ten-year running average, the Lower Basin could place a compact “call.” A compact call would result in forced curtailment of water uses, according to priority date, in the Upper Basin. Farms, ranches, cities, and industries that depend on Colorado River water could be forced to go without. The disruption to Upper Basin States’ economies and quality of life is difficult to imagine.

Demand Management

In an effort to stave off a compact call, the four Upper Basin states are considering the development of a Colorado River “demand management” program. Demand management would be a program under which water users are compensated to temporarily and voluntarily cease water use. TU supports this concept because we see it as a step towards balancing water supply and water demand on the Colorado River system, and such a program also has potential to produce stream flow benefits. We also support the notion of allowing water users increased flexibility in how they use their water, including the option of using less or even no water on a temporary basis.

Over the past several years, TU has participated in policy discussions around the feasibility of demand management. We have also worked with water users to develop on-the-ground demand management demonstration projects. In these projects, we have raised funds to compensate farmers and ranchers for temporarily foregoing water use, and we use the projects to conduct research on the impacts of demand management on crops and stream flows.

Through both our policy work and our on-the-ground projects, we believe that a program that compensates water users for foregoing water diversions on a temporary and voluntary basis has potential to help address the supply and demand imbalance and to improve flow conditions in the Colorado River basin. As we have seen over the course of this series, these collaborative efforts offer real potential for both basin-level and localized benefits as we face the challenges of a warmer, drier future.

Conclusion

Over the course of this series we’ve explored the past and present of water use in the West and how TU is working for a future in which all water users—Tribes, farmers and ranchers, anglers, boaters, fish and wildlife, municipalities, and all those who rely on and enjoy the West’s waterways—have a reliable and abundant water supply. While this initial series is coming to a close, stay tuned for more deep dives into specific issues in the West both here on the blog and in the podcast feed. Together we can find solutions through collaboration and meet the challenges of the twenty-first-century West in innovative, inclusive, and equitable ways.

Table of Contents

Western Water 101

- Introduction to Western Water

- Conflict to Collaboration

- TU’s On-The-Ground Projects & Natural Storage: How Flipping the System Benefits People & the Environment

- TU’s Work with Federal Agencies: How Our Research Advocates for Change in the Bureau of Reclamation

- TU’s Work for Legislative Change

- Wrap-up: The state of our hydrology today in the Colorado River Basin

- Take Action