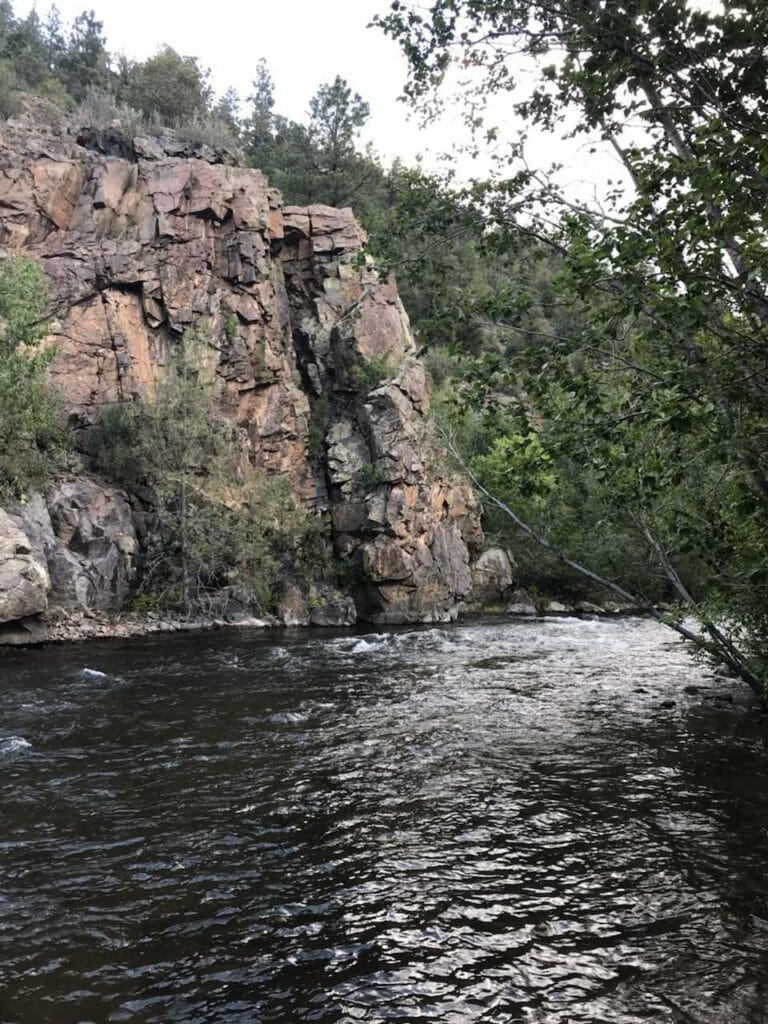

The lifeblood of the Village of Pecos, the Pecos River flows through public and private lands in a narrow canyon flanked by in aspen, Gambel oak, and mixed conifer. The Pecos boasts a fun salmon fly hatch in early summer, and I love how spooky the fish are in autumn, when elk bugles echo, the banks blaze with yellow cottonwoods, and the water resembles the air above, cold, clear and sprinkled with tiny mayflies.

Like countless thousands, I learned to fish on this river. Even after the Santa Fe real estate boom and the consequent rise in the number of anglers on the banks, the Pecos remains my trusted friend, generous, and honest. By now I’ve learned that I never fish there alone anymore; my childhood is always my companion.

Back then, when I used to slake my thirst by drinking straight from the river, I was unaware that the upper Pecos Canyon (Terrero) had been mined in the 20s and 30s. I didn’t know that the road from Terrero to Cowles had been graveled with mine tailings, or that such beautiful and natural-looking rivers are generally capable of producing bigger fish than the Pecos was known for. Large fish were rare in the 70s and 80s, for they could only grow so big before they died. I was almost 30 years old before I heard the term “toxic leachate.”

Remediation of the Terrero site, though imperfect, has definitely improved the Pecos River. The paving of the road and the containment of the tailings led to recovery of insect populations, more and bigger trout, and happier anglers including day-trippers and guided clients.

Alas, our honeymoon may be a short one. Last week we learned that Terrero could be mined again, this time by Comexico LLC, a subsidiary of Australia-based New World Cobalt. The company has applied for a permit to conduct exploratory drilling on the Santa Fe National Forest in hopes of finding promising deposits of precious minerals in what has always been one of New Mexico’s most popular public recreation areas.

It’s the latest in the trend of mining corporations trying to open shop in what the greater public views as treasures. Like the proposed Pebble Mine in Alaska’s Bristol Bay watershed, this Pecos project makes no sense. Pecos Canyon traffic, already slow, will increase. Noise and dust will be factors, as will road construction and the location of tailings piles. Even as impacts of past mining continue to be an issue, seepage from renewed mining will need to be contained, but in an overstocked forest vulnerable to high-intensity wildfire and a post-fire flooding.

How will Comexico guarantee that its operations won’t dump pollution into the Pecos? It can’t, and it knows it can’t, and it knows that we know it can’t. Mining companies understand by now that their promises of enduring environmental safety and economic prosperity will be measured against their poor track record for keeping such promises. The companies will proceed anyway, because that’s what they do.

In recent years, the Village of Pecos has devoted considerable energy to beefing up tourism capacity in its corner of San Miguel County. In the long-term interest of local hunting, camping, farming, and fishing, the Upper Pecos Watershed Association (UPWA) has developed a Watershed Based Management Plan in order to protect and improve water quality in the river and its tributaries. The plan identifies projects throughout the watershed, several of which have already implemented by UPWA and its partners.

At the state level, the New Mexico Environment Department worked with UPWA to develop this plan. The state legislature created and funded the Pecos Canyon State Park, another UPWA initiative. And in the 2019 session, the legislature also created the New Mexico Outdoor Economy Division, to enhance and develop the state’s recreational assets and to attract businesses involved in outdoor recreation. Given the massive scale of New Mexico’s existing outdoor economy, such initiatives promise more jobs, new businesses and sales tax revenues.

In Albuquerque and Santa Fe, where approximately one quarter of New Mexicans live, leaders have spent decades (and millions of dollars) promoting the state’s unique scenery and outdoor lifestyle, filling hotels, restaurants, and art galleries. Along with fishing, they’ve sold hunting, skiing, rafting, hot air balloon rides, opera tickets, along with billions of dollars in real estate.

For its fishing alone, the Pecos River is responsible for much of this growth.

Perhaps naively, I continue to be amazed when mining companies foist their own economic visions upon communities and expect to be taken seriously. They’re bringing in jobs, they say, regardless of how few those jobs may be in comparison to preexisting ones, or how mining jobs will only last as long as ore yields and prices hold up. Or how, in the context of the jobs that New Mexico, the surrounding region, and the Village of Pecos are already planning to create through decisions based on existing and planned infrastructure, mining jobs will be subtractive.

The apparent response from a mining company based on another continent? “You are free to take ownership of your economic destiny, leveraging American public lands and the natural resources they contain. Until we decide that you’re not.”

Toner Mitchell is the water and habitat coordinator for TU in New Mexico. He lives and works in Santa Fe.