Paris Creek in Idaho is a tributary to Bear Lake. Removal of an old hydropower plant will prevent dewatering of 3 miles of Paris Creek for most of the year allowing migratory cutthroat trout to access spawning grounds. Brett Prettyman/Trout Unlimited.

The Bear River in Utah, Wyoming and Idaho is important to native cutthroat trout and the people who live along its path

Editor’s note: Our “American Places” series highlights lands and waters that make this nation unique. These places are near and dear to many and worthy of sharing in hopes of creating more advocates for the treasures so many Americans cherish.

Sitting on a 5-gallon bucket in the pre-dawn marsh mist at Bear River Migratory Bird Refuge, I fought to stay awake until waterfowl shooting hours opened. We had been up for hours driving from Salt Lake City to the refuge in northern Utah. It took us another 30 minutes to canoe in the dark to my friend Pete’s secret spot.

Watching the water gently flowing around my legs and the surrounding cattails was mesmerizing and doing little to keep me from nodding off. I focused on the water destined for the Great Salt Lake and started to visualize where it had originated. My mind rapidly took me some 500 river miles through two other states to the headwaters of the Bear River in Utah’s Uinta Mountains.

Memories of camping, fishing and keeping a running tab on the number of moose we saw over three days (the final tally was 16) from our campsite with family and friends came rushing back.

Since that time on the marsh with Pete many years ago I’ve come to know the Bear River, the largest tributary to the Great Salt Lake and longest river in North America that doesn’t flow to the sea, a little better.

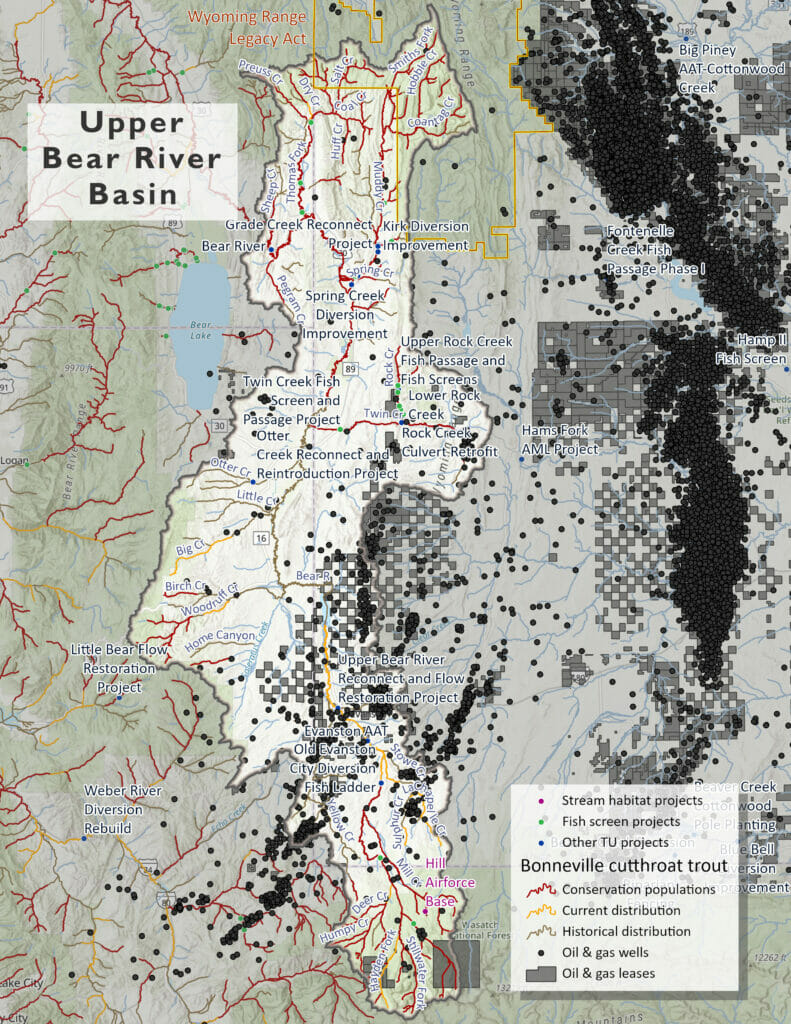

A recent tour offered by Trout Unlimited and the Western Native Trout Initiative, along with other partners, helped check more Bear River miles off my map. Over three days, the group visited 15 projects along the river in Utah, Wyoming and Idaho to show partners from the Resources Legacy Fund work they have funded in the past and possible work their Open Rivers Fund could help support going forward.

Along the way tour participants met landowners eager to make improvements to their water infrastructures to prevent trout from ending up in fields, learned about the value of reconnecting tributaries and heard how one group wants to restore the land back to the way it was in 1863.

A busy first day had the group stop at seven sites from headwater tributaries in Utah and then into Wyoming. Among the stops was Evanston Dam. The failing dam once helped provide water to the town of Evanston, but the water source changed and the dam remains a barrier for migratory cutthroat trout as a well as a danger to people.

Working with landowners

Trout Unlimited and the Natural Resources Legacy fund, along with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Wyoming Game and Fish, Wyoming Wildlife and Natural Resources Trust, Wyoming Department of Environmental Quality, and Shaun Sims, the landowner where the project is taking place, worked to replace a typical push-up dam used by many landowners with a head gate and restoration efforts.

On Day Two of the tour, the group stopped along the river north of Evanston, and heard from Sims. He mentioned how he has seen the river flowing north out of Evanston has been channelized over the years as a result of people trying to control the flow to access the water they are permitted to collect. This leads to more erosion of important ranch lands next to the river, particularly during high water.

“To be honest, I had my doubts. But that first water year after it was installed was a record flow and it handled it,” he said. “It’s 3 years old now and I think we are good for its lifespan.”

In addition to helping control the irrigation flows, Sims is hoping the restoration on the Bear River near his property will lead to another important part of his life.

“When I was a kid, I used to come down here and fish all the time. I loved it and now there are no fish,” he said. “Hopefully we will get fish back in here.”

If you unbuild it, they will come

After visiting with another landowner in Wyoming, the group moved to Bear Lake on the Utah/Idaho border.

Trout Unlimited and multiple partners have been working for years to remove barriers in tributaries to Bear Lake to allow native Bonneville/Bear River cutthroat to reach headwaters where they can spawn.

During lunch, Utah Division of Wildlife Resources Bear Lake Project Manager Scott Tolentino talked to the group about the importance of collaboration and the success the reconnecting effort has had on the fishery.

Irrigation and power producing infrastructure have been blocking cutthroat from accessing tributaries or funneling adults and fry into farmer’s fields and canals for decades. Removing or replacing the infrastructure with fish friendly designs has changed how the states manage the Bear Lake fishery.

For years cutthroat trout in the lake would stage at the mouth of the tributaries preparing to migrate upstream to spawn.

Due to the barriers in the tributaries Utah created a fish trap at the head of Swan Creek in the early 1970s and started to collect eggs to grow the cutthroat in a hatchery before returning them to the lake.

Since the work to remove barriers and create safe migratory passage for the fish, the numbers have flipped.

“The whole idea was to maintain these fish. There wasn’t a lot of hope for natural recruitment from the fish,” Tolentino said. “We never thought we would have the opportunity to cut back on stocking and use natural recruitment as a main management tool. It’s really exciting.”

In the mid-1990s, efforts were made to improve headwaters habitat on tributaries and provide better access from, and back to, the lake.

“Boy have things changed. In the early 2000s we only saw about 8 percent of the cutthroat that that we sampled put in the lake coming from natural recruitment,” he said. “We have been able to cut back on the number of fish we grow in the hatchery by 47 percent and maintain the gillnet catch rates. In fact, in the last three years we have had the highest numbers ever recorded. We are seeing that despite stocking a lot less fish. Nothing else out there but the habitat work, screening and access can account for the difference.”

The group then toured three projects on the tributaries to see work that has been completed and some that is currently being funded.

On Day Three, two stops were made on Bridger-Teton National Forest Service lands in Wyoming and another stop was made on a landowner’s property in Idaho to hear about work planned on his property to reconnect a Bear River tributary to the main stem of the river.

Back to the 1800s

The final stop on the tour was a special one. A place that has many names: Battle Creek; Beaver Creek and Boa Ogoi.

Settlers in southern Idaho named it Battle Creek after a clash that took place in December of 1863 involving the U.S. Army Cavalry and the Northwestern Band of Shoshone. The event is more commonly known and the Bear River Massacre as more than 400 Shoshone people were killed at their traditional wintering ground along the river and some hot springs.

The Northwestern Band of Shoshone Tribe has been working to purchase the sacred land in honor of their ancestors lost in the massacre. Some of the land has been donated to the tribe and a large portion was purchased in 2018. Efforts are being made to make a memorial on the site, but money still needs to be secured for a building an amphitheater.

In the meantime, there is another way the living tribal members see as a way to commemorate their ancestors.

“The elders told us there is no point in building a visitors center if we don’t restore the land,” said Brad Parry, a tribal member leading up conservation work on the neglected landscape. “They told us they want this land back to the way it was when the massacre happened. For those who died to have a peace we need to restore the land to as natural as possible.”

That means removing hundreds upon hundreds of invasive and nonnative Russian olive trees along Beaver Creek and along the Bear River. The goal is to restore native vegetation and a meandering creek to the land hoping to attract native wildlife to Boa Ogoi (the site of the massacre).

Bonneville cutthroat trout were a part of the picture back in the 1860s and it will take a lot of work to restore the creek and the water quality to make it suitable for cold-water fish. Trout Unlimited, the Natural Resources Conservation Service, Utah State University, the Bear River Environmental Coordinating Committee and U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service are collaborating with the tribe to complete the work.

Threats along the entire Bear River

While there is a lot to celebrate along the Bear River and its 500 miles, there are also threats to the river, the landscape and the wildlife that rely on its waters and riparian zones.

Extended drought, wildfires and human development all pose a serious risk to the tri-state undammed river.

Trout Unlimited is particularly concerned about something call speculative leasing. This system allows anonymous speculators to nominate millions of acres of public lands for oil and gas leasing even in areas where oil and gas exploration is highly unlikely to produce viable energy resources.

This creates mounds of paperwork pulling limited federal agency resources off other important projects. This system does not benefit American taxpayers and creates unnecessary land management conflicts with fish, wildlife, outdoor recreation and other multiple-use activities.

Back on the bucket

Back on the refuge in what now feels like the ancient past the sounds of pending dawn woke me from my Bear River trance as we could hear the marsh coming to life.

“It’s almost time,” Pete said as the sun peeked over the Wellsville Mountains.

I took a final look at the water swirling around my legs, thanked it for the memories and looked to the sky for incoming blue-winged teal.

It is past time to head back to the marsh with Pete and perhaps reflect on other epic adventures I’ve experienced on the Bear River, like catching migratory Bear River cutthroat trout in a Wyoming Range tributary 50 miles from the main stem river.

Brett Prettyman is a communications director for Trout Unlimited. He is based out of Salt Lake City.