Armed with mountains of scientific data, Trout Unlimited is starting to dig into reconnection and stream restoration efforts in a large, important watershed in western North Carolina.

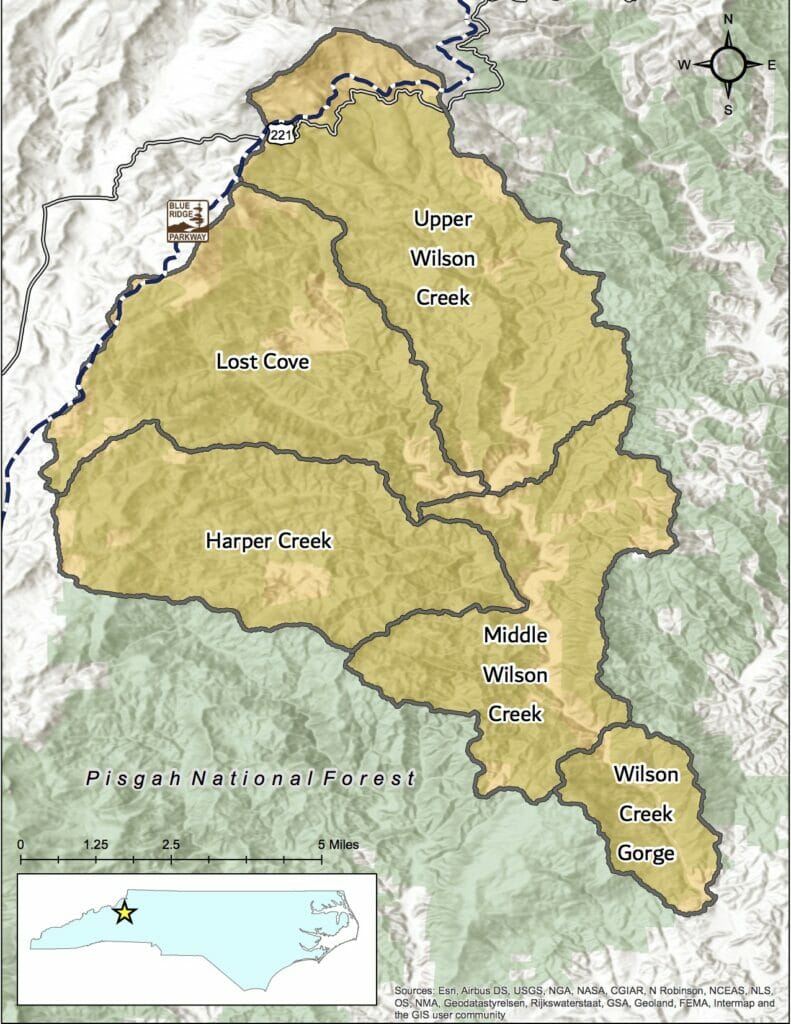

Over the past year, carefully trained TU volunteers fanned out across the Wilson Creek watershed to survey the condition of Wilson Creek and its many smaller tributaries.

They identified dozens of barriers that block the movement of fish and other aquatic organisms from moving freely throughout the water system.

“The entire watershed has been covered,” said Andy Brown, who manages TU’s restoration work in the Southeast. “We not only looked at barriers, but we also surveyed roads and trails to assess problems with sedimentation.”

Wilson Creek is a designated Wild and Scenic River, and the area within the Pisgah National Forest is immensely popular for recreation, including hiking, biking and paddling.

Wilson Creek itself is a popular trout fishing destination, with both wild and stocked fish. Many of the creeks in the watershed boast populations of native brook trout and wild rainbow trout.

Barriers can include dams, but in the Wilson Creek watershed most are culverts with perched outflows well above the downstream outflow pool. Fish and other creatures can pass downstream but cannot go back upstream.

Volunteers conducted 122 surveys. They found 23 cases of “severe” barriers, and 15 that were deemed either “significant” or “moderate.”

Thirty-seven barriers were on ephemeral streams, which flow only part of the year, so they were not included among the barriers to aquatic organism passage.

Only 16 barriers on streams with year-round flows were deemed “insignificant” and even fewer — just 10 — were found to not impede passage at all.

Additionally, volunteers spent 167 hours surveying about 10 miles of roads and trails. To date, they have identified 66 locations where roads and trails are eroding and that runoff is reaching a stream in the watershed.

With the data in hand, Brown and his team will now prioritize sites for restoration and reconnection work.

Reconnecting stream sections provides trout and other fish access to additional habitat that can be used for spawning, feeding or for thermal refuge during the summer months.

One large project is just getting underway.

TU is partnering with the U.S. Forest Service to replace a low water bridge on the access road to the Mortimer Campground. The low bridge crosses Thorps Creek, a stream populated with wild rainbow trout.

Replacing the low water bridge with a raised bridge will not only improve fish passage but will solve a long-standing access problem for the campground. At times, campers have been stranded when high water made the creek impassable.

The campground closed on Aug. 10. The project is slated to be complete later this fall.

Click HERE for a story about the project by Mark Jackson of the Caldwell Journal.

Work on addressing the fish passage barriers, as well as erosion-prone roads and trails, will begin in earnest in 2021.