Western Native Trout Challenge: Pursuing one of the world’s rarest trout across scorched earth

Editor’s note: Daniel Ritz is fishing across the Western United States this summer in an attempt to accomplish the Master Caster class of the Western Native Trout Challenge. He will attempt to land each of the 20 native trout species in their historical ranges of the 12 states in the West. You can follow Ritz as he travels across the West by following Trout Unlimited, Orvis, Western Native Trout Challenge and Montana Fly Company on social media using the #WesternTroutChallenge.

Shortly before departing for the nearly 20-hour drive south from my home in Idaho my contact in New Mexico casually mentioned on a call how the snowpack was only 16 percent compared to the average and to keep my fishing expectations low.

Heading south on U.S. 491 towards Gallup I spotted a sign for the small town of Little Water on the Navajo Nation. Chills came over me as I realized I was about to experience firsthand exactly how little water there is for the two southernmost trout of the United States.

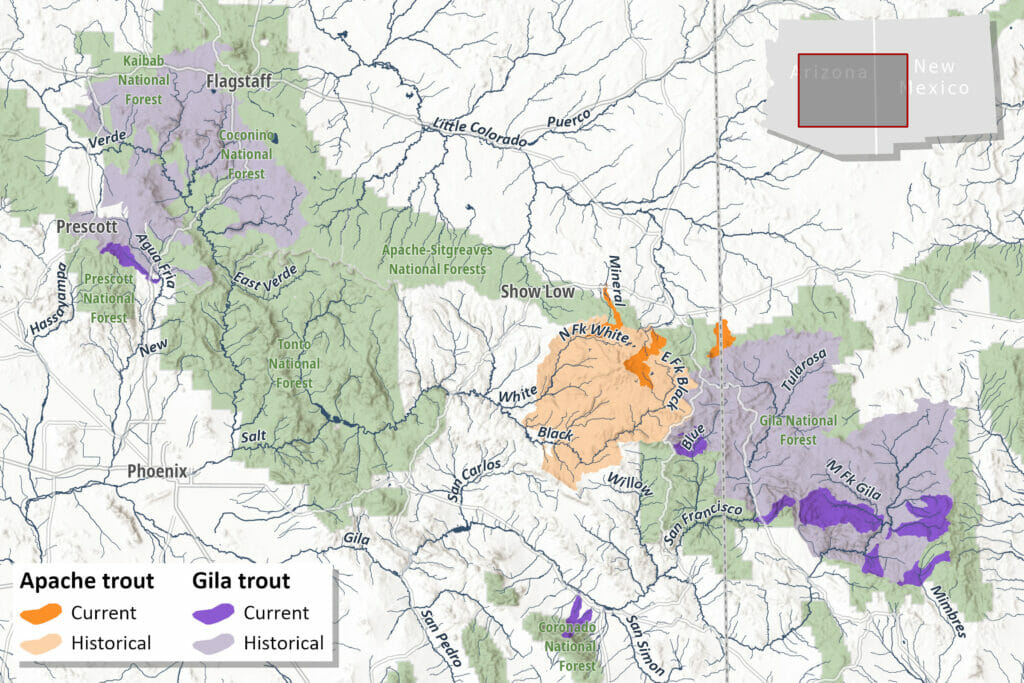

Canaries of the Gila: New Mexico

It was late on Saturday afternoon when I finally began climbing the backroads through the Gila National Forest toward Willow Creek, where I was to meet Jeff Arterburn, president of the Gila-Rio Grande Chapter of Trout Unlimited. Arterburn’s chapter, along with other Trout Unlimited New Mexico State Council board members, were converging to perform a habitat survey.

The survey happens twice a year on three segments of Willow Creek to analyze stream restoration progress and note changes in stream features aimed to set the standard of reporting necessary to pursue funding for future stream restoration projects.

“They are the quintessential canary in the coal mine and as they go, the Southwest goes.”

Jim Brooks

Major rehabilitation of Willow Creek is necessary after it — and all but only three streams containing Gila trout in all of New Mexico — were torched in the 290,000-acre Whitewater-Baldy wildfire of 2012, the largest wildfire in the history of New Mexico.

“That fire struck at what is the center of the universe of Gila trout,” said Jim Brooks, formerly of the U.S Fish & Wildlife Service.

“If you want the story of Gila trout, I think you’re starting in the right place, talking to that guy, ” said Toner Mitchell, New Mexico Water and Habitat Program manager for Trout Unlimited, pointing across the campground to Brooks, sitting alone at a picnic table “He’s probably more responsible for Gila trout existing on this planet than anyone else.”

After walking Willow Creek with Arterburn and New Mexico Trout Unlimited Council Chairperson Harris Klein, I sat down with Brooks and listened, captivated, as he walked me through his more than 40-year relationship with the region’s fish and wildlife.

Born in a small mining town in Arizona, Brooks said he dropped out of engineering school after being inspired to pursue a career he “really cared about.” That line of thinking led him to a literal coin-flip between fish and their habitat and wildlife management. The coin landed on tails. Fish it was.

Here’s a map of Daniel Ritz’s summer travel plans, where he hopes to catch the 20 native trout and char species and earn his master class designation under the Western Native Trout Challenge.

Beginning his career with Arizona Game and Fish, then New Mexico Department of Game and Fish, Brooks eventually ended up with the USFWS where he worked on native fish, beginning his focus on Gila trout in 1987.

“Jim Brooks spent his whole life restoring populations, then one year before he retired, the fire crushed all of his work. I think of how that would feel,” said Jill Wick, native fish program manager for New Mexico Department of Game and Fish.

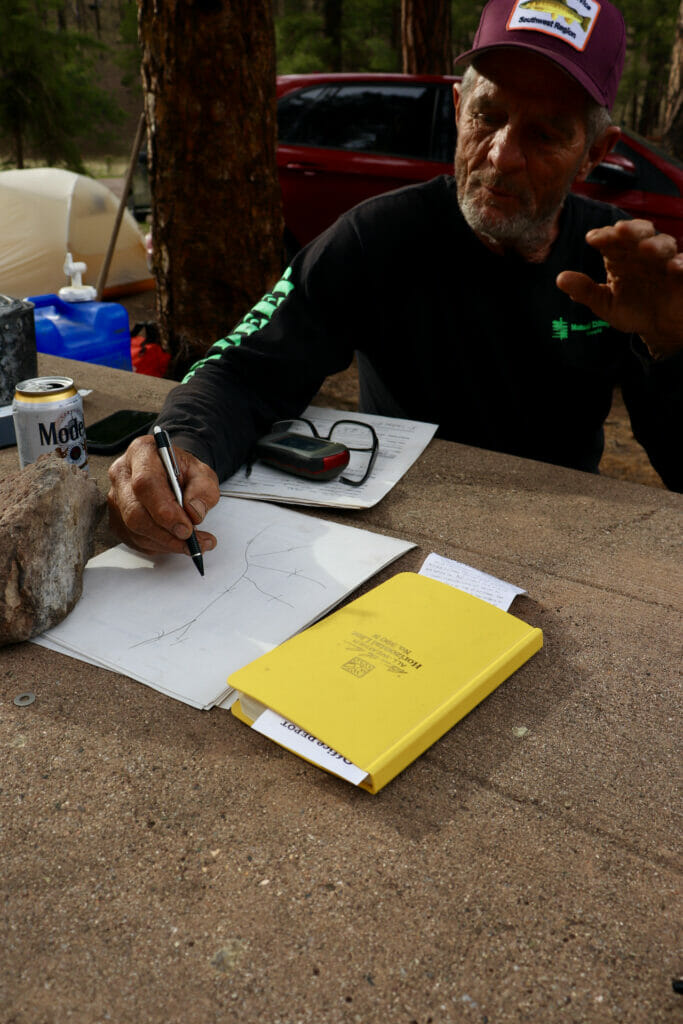

Brooks’ exhaustive experience restoring populations of Gila trout was obvious as he drew by memory a flawless to-scale map of the Gila trout’s historic habitat streams and the genetic lineages they contained on a piece of scrap paper he found on the table.

“I have to ask, how do you do it Jim?” I asked. “You work for decades, fighting changes that are beyond your control, see success, and then have your life’s work ripped out from under you a year or so before you retire. You build it up, it all burns down, or the water just isn’t there? How do you keep coming back?”

Sitting straight up, taking off his cap and wiping his brow, Brooks put his hands out in a gesture that hinted he was shifting from what to him is objective scientific realities to a place of emotion.

“Daniel, you have to understand,” Brooks said, his voice cracking. “This work, these fish… I don’t even know. I’m from here. It’s like this is a part of me. It’s my passion. It’s cost me two marriages, lord knows how much money, probably 80 girlfriends. When it all burned, it wasn’t even a choice. There was no way I could give up.”

The next morning, Mitchell, Klein and I set out to see if we could find any Gilas in Willow Creek’s few remaining pools.

We unsuccessfully bushwhacked through the apocalyptic setting for hours without a sign that we even spooked a trout.

Walking along Willow Creek, its shallow, empty waters a whimper of its former rushing, rich self, back toward the trucks, the wind suddenly exploded through the bare ponderosas, eliciting a sound more like a scream than the standard “whoosh.”

I was overwhelmed with how, sadly, the experience, a failure, felt fitting for this story. I told Mitchell, who described the scene as “nuked,” that our struggles that morning felt like a personal crash-course in context.

Leaving Willow Creek, I followed Arterburn up and over Bursum Road, away from Willow Creek and toward the now deserted mining town of Mogollon and out to New Mexico 180. Driving along the rim, the vast burn scar of the Whitewater-Baldy fire was overwhelming.

Arterburn led me to Whitewater Creek, a river system 15 to 20 minutes north of the small town of Glenwood, where in his standard, gentle tone he assured me we would find Gila trout.

I have to admit, out of the gate I was skeptical. From just outside the Gila Wilderness, deep in the National Forest, we had arrived at what looked like a community park.

“Creating populations that are more connected and widespread are essential. That’s why we’ve focused on Whitewater (creek),” said Wick.

The connectivity extends far beyond the holding potential of the Whitewater Creek fishery itself. At Whitewater Creek, I was standing at what Kirk Patten, chief of fisheries for New Mexico Department of Game and Fish, called the intersection of “recreation, conservation and the trip of a lifetime.”

Following the mosaic of fires of the early 2000s, including the nearly 300,000-acre Whitewater-Baldy fire of 2012, New Mexico Department of Game and Fish and other stakeholders discovered that Gila trout were the predominant species remaining in Whitewater Creek. Over the next three years, they carefully monitored and managed the streams to ensure exclusively Gila trout remained. Just this past fall, Gila trout were planted in the upper portions of Whitewater Creek, ensuring the entire watershed is home only to native Gilas.

In the bright sun of the early afternoon in New Mexico, I finally spotted my very first Gila trout. Visible at first only as a shadow, it moseyed from underneath a large boulder on the far side to a pool beneath our lookout, to within the feeding lane created by a waterfall before quickly scurrying back to safety.

Later that afternoon, after assuring Arterburn and a few of his chapter members they could leave me in good faith considering we had at least spotted a Gila, I was hopping from pool to pool, waterfall to waterfall, miles upstream from the picnickers bringing one hand-sized trout to the net after another. The smile didn’t leave my face as I spent the next several hours coaxing Gila out from the safety of their plunge-pools.

Their eagerness to take dry flies, in addition to making for a fun angling experience, alludes to the Gila’s livelihood.

Life, as harsh as it, is all about opportunities, and one must take advantage of them when they occur. Sometimes, maybe the best part of an otherwise challenging environment is the glory of opportunity.

“The fun part about working with Gila trout, and it is fun, is that you’re working with species that isn’t on the decline,” Patten said. “Often, you’re pursuing something that is a lost cause, a failure. Gila trout isn’t like that.”

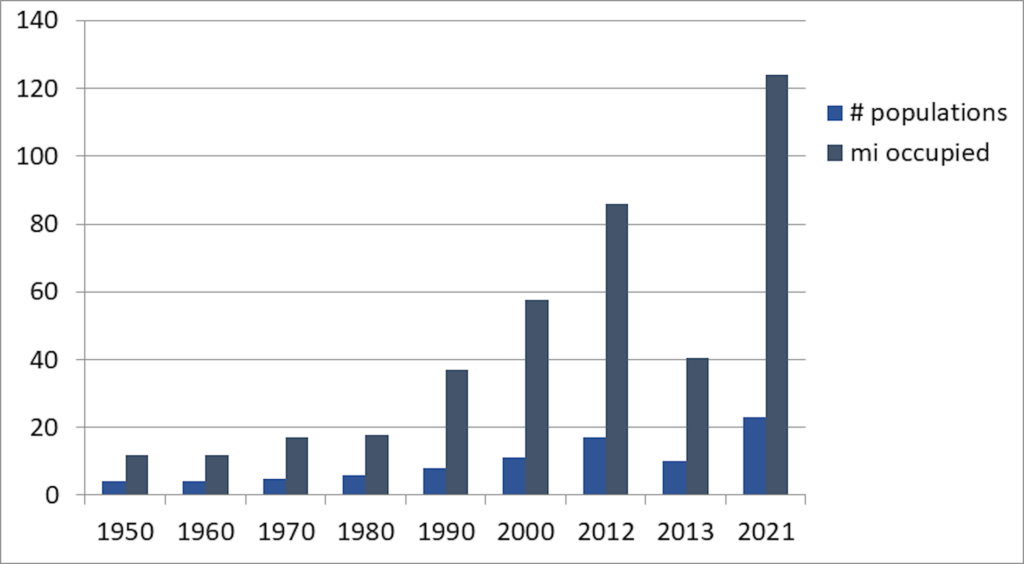

In the years following the 2012-2013 fires in Gila country, Patten, Wick and their teams noted as few as eight total populations of Gila trout. Since that time, Gila have grown to more than 20 sustainable populations in New Mexico

Walking back through the lower Whitewater Creek catwalk section, I realized that Whitewater is exactly one of those opportunities. From the tragedy of a fire at the center of the universe, continuance became possible.

Only, if like Jim Brooks, you decide to never stop trying.

However, I must admit, Whitewater Creek was a bit trafficked for my personal tastes so I continued north, crossing the public-private land patchwork that led to Mineral Creek, where I spent a full day catching beautiful, small wild Gilas in intense red rock slot canyons under mesmerizing waterfalls. High in the headwaters, deep in the canyons that giant southwestern sky threatened rain, and I decided that I didn’t want to be in those canyons when the rain did come. It was time to move north and west.

The rain never did come.