Named for the work of a Jesuit priest, this panhandle river is true holy water

About a century ago, rumor has it that renowned author Zane Grey would pay his friends to get up before dawn and go stand in the prized steelhead runs of Oregon’s Rogue River. They wouldn’t fish, mind you, although they might wave a fly rod around to make it look like they were chasing the Rogue’s famed chromers. But really, they were just placeholders — Grey’s minions who saved prime water for the boss, who was back at the cabin, likely still asleep.

When I first heard that story, my perspective on the prolific writer — he of Riders of the Purple Sage fame — completely changed. “What a tool,” I remember thinking upon learning this news as a young journalist.

A century later, as I drove the road along northern Idaho’s St. Joe River in search of unoccupied water during a global pandemic, I had a change of heart. Old Zane was on to something. It seemed that every conceivable pullout was occupied. I had arrived on a Monday afternoon, and, predictably, the river was almost vacant. But by Wednesday evening as I searched for a spot to take in the late-day PMD hatch, it appeared that every fly fisher from Pendleton to Bonners Ferry had worked their way into my tiny slice of public lands paradise.

Maybe Zane Grey wasn’t such a jerk after all. If I’d had the scratch on this particular evening, I might have hired a placeholder or two, myself.

Every deep, green pool along the stunning river boasted an angler, sometimes two. I recognized a lot of 1A Idaho license plates — visitors from Ada County, home of Boise. These folks had driven almost as far as I had to get to the river. For me to get to the upper St. Joe, I had to leave my home in Idaho Falls and drive north into Montana, past Missoula and then over the mountains. By the time I got the camper leveled, it had been a good eight hours, door to campsite. There were lots of plates from Washington — likely anglers from Spokane. And some Oregon plates, too.

The St. Joe isn’t really close to anything. It’s a good 100 miles from where I was camped near the end of the road at Spruce Tree Campground to where the river flows into the slackwater of Lake Coeur d’Alene just downstream of St. Maries. I’d planned a weeklong trip to the St. Joe, largely because I assumed its remote location would be ideal for social distancing while the coronavirus continued to ravage the nation. That the river boasts some really nice west slope cutthroats and some of Idaho’s reclusive bull trout … well that didn’t hurt, either.

First look

After topping the Coeur d’Alene Mountains outside of St. Regis, Mont., and driving the Little Joe Road down into the big timber region of the Idaho panhandle, I got my first glimpse of the St. Joe Country. Massive spruce, fir, cedar and fabled Idaho white pines drink deeply from the slopes of the mountains thanks to ample winter snow and frequent spring and summer rains. The largest white pine ever harvested came from the banks of the St. Joe — it contained enough marketable wood to build three houses when it was felled in 1911.

This is tall country, but not necessarily severe. Deep, evergreen gorges channel runoff and rain into dozens of little streams that collect water from dozens of others. Eventually they all feed the St. Joe. The river is named in honor Father Pierre-Jean Desmet, a Jesuit missionary who traveled extensively around the West and Northwest in the mid-1800s. He’s credited with working with Sitting Bull and the Sioux to reach the Treaty of Fort Laramie in 1868. He also established a mission along the Bitterroot Mountains in Montana and the Sacred Heart Mission in Cataldo, Idaho, east of Coeur d’Alene. He might have been the most-traveled missionary ever — his work took him north into Canada near present-day Edmonton and across the boreal north, where he worked with Chipewa and Athabascan tribes. He did all this from his Jesuit chapter home base in St. Louis, Mo. While Desmet has never been canonized by the Catholic Church, the river bears the name of his most-famous mission, St. Joseph, which was built in 1838 for the Pottawatami Indians near what is now Council Bluffs, Iowa.

And, while the Jesuit connection is likely lost on many who fish the St. Joe these days, for some, the river is, indeed, holy, blessed water.

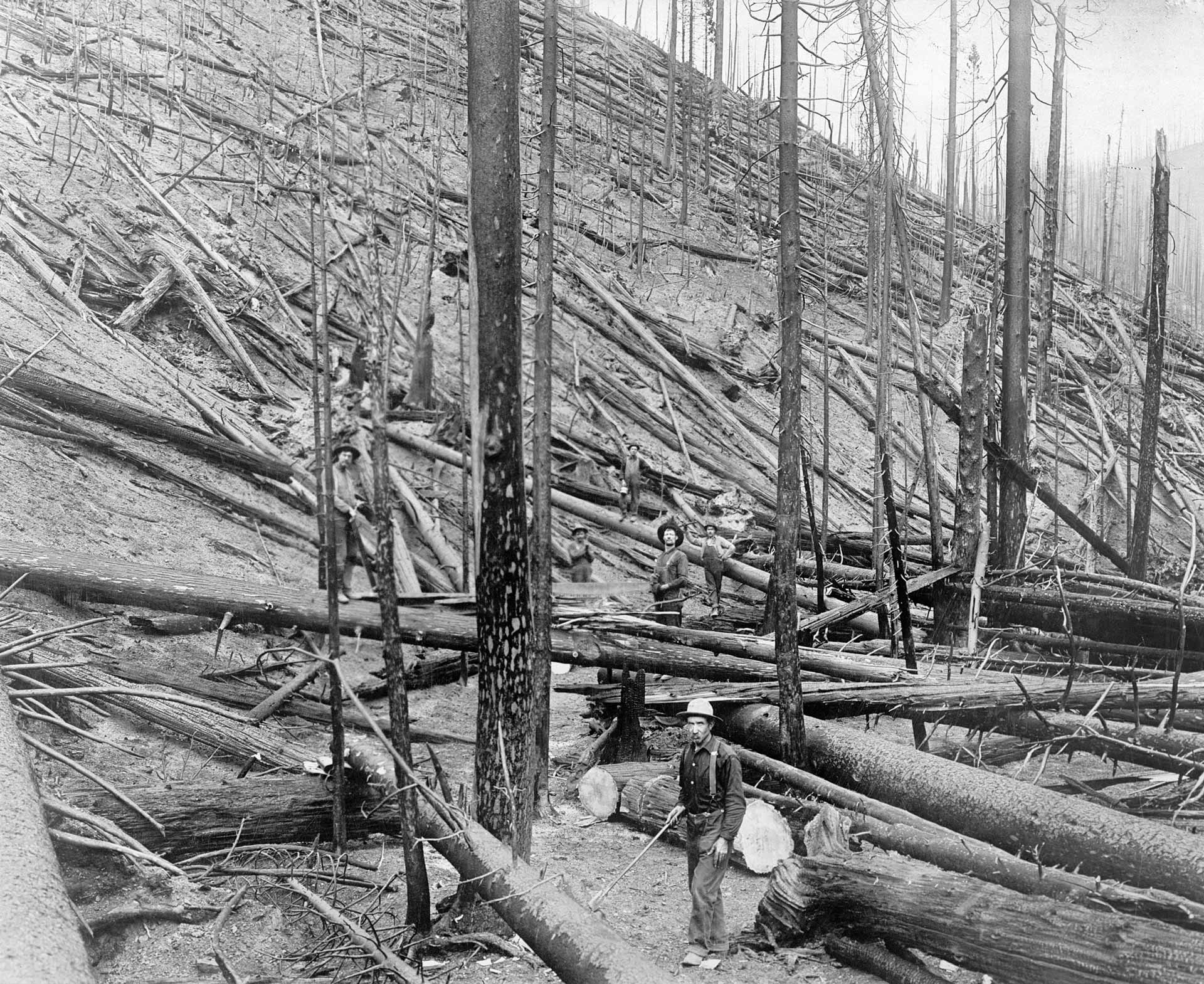

Even high into the mountains, the St. Joe carries a lot of water, and, generally speaking, it carries that water quickly. More than a century ago, the river was harnessed to deliver logs to market — the St. Joe Country is steeped in timber history, and the area boomed just after the turn of the last century. Much of the timber standing today is second-growth, both due to the unchecked harvest of giant white pine trees, which were highly prized for their near-perfect, 200-foot, knot-free trunks, and due to the great Idaho fire of 1910. The blaze, ironically, was sparked by a newly constructed logging train that emitted sparks into a drought-stricken forest. By the late 1930s, the largesse of the region’s forests was largely gone and nude mountain slopes contributed to a series of record floods that eventually reclaimed the river from the people who tried to tame it. The good times for loggers and the timber economy in the basin, at least at any significant scale, were over.

Much of the timber standing today is second-growth, both due to the unchecked harvest of giant white pine trees, which were highly prized for their near-perfect, 200-foot, knot-free trunks, and due to the great Idaho fire of 1910. The blaze, ironically, was sparked by a newly constructed logging train that emitted sparks into a drought-stricken forest.

As trout streams go, the St. Joe is among the most beautiful I know. Aptly designated a wild and scenic river in 1978 (which likely saved the upper half of the river from the perils of suction dredge mining and potential dam construction), it runs cold and impossibly clear after runoff ends some time in June. It drains almost 2,000 square miles of the Idaho panhandle — it starts as a trickle beneath peaks in the Bitterroot Mountains with names like Neversweat, Cascade and Gold Crown. Getting to these smaller upper reaches is doable via old Forest Service logging roads, but your truck may never forgive you — I know mine still bears a scar or two. Your best bet for reaching the upper stretches of the St. Joe is by foot or on horseback.

Farther downstream, starting about where I spent the week at the Spruce Tree Campground, the river gathers together a host of small tribs and spring seeps and carries some steam. In spots, a sure-footed angler can wade across it with a little effort, but in others, it runs deep and swift, careening into sheer basalt faces and tumbling over massive chunks of displaced granite and quartz. It slices through some of the best elk country in Idaho, and it’s home to both black and grizzly bears, wolves, mountain lions, lynx, deer, grouse and, farther downstream, wild turkeys.

But for anglers, the treasure lies with the St. Joe’s native trout.

The fish

Unlike other rivers that drain from the Idaho backcountry — fabled waters like the Clearwater, the Salmon and the Snake — the St. Joe was never a salmon or steelhead river. Separated from the ocean by Coeur d’Alene Lake, the river is home to native west slope cutthroat trout and federally protected bull trout. Both are managed by the Idaho Department of Fish and Game under catch-and-release restrictions, and angling for both can be excellent.

On the Monday afternoon I arrived, my old fishing dog, Phoebe, and I wandered around a bend in the river near camp toting a pair of fly rods — a 9-foot 3-weight for cutthroats, and a heavier 9-foot 6-weight for bull trout, should the opportunity to swing a streamer arise. Just a couple hundred yards from our campsite, we came upon a deep, green pool where the river tailed out and then took a turn up against a sheer rock cliff. Right up against the rocks, a steady caddis hatch was happening, and the river’s cutthroats were coming to the top.

It took but a cast or two, and our first St. Joe cutthroat came to hand — a stunning foot-long trout, the progeny of the fish that survived the logging booms of years gone by and still propagate in this almost-pristine river today. We caught another nice cutty, but then things slowed down. We got a few looks from fish climbing from deep within the water column, but the caddis didn’t attract any more takers.

But these fish are cutthroats, after all, and while they can get a little picky at times, they’re generally opportunists. I changed flies to a big, fat Chernobyl and the new fly helped me connect with a stunning 16-inch cutthroat right along the edge of the pool. Phoebe and I fished the pool for an hour or so, changing flies often and finding different seams over which to cast. Before we knew it, the sun had dipped behind the cliffs enough to shade the deepest part of the pool, up against the basalt face.

The shaded water took on a dark, ominous countenance — no longer could I peer into the emerald green depths and watch fish rising to inspect my fly. What was happening now beneath the surface was anybody’s guess. I grabbed the heavier rod equipped with a big, weighted mottled yellow Slumpbuster. If a St. Joe bull trout lurked in the depths of this pool, I thought, this might by the fly that would pull it off the bottom.

I stepped over other smooth river rock to the center of the river so I could reach the farthest seams with the streamer. Moments later, a chuck-and-duck cast and a quick mend put the fly in the pool’s deepest corner. Honestly not expecting much, I let the weighted streamer sink into the depths and drift a bit. A few moments later, I began a slow strip, and on the second pull, the line stretched tight. I knew right away that I hadn’t hooked another St. Joe cutthroat — this was different. There was no panic on the part of this fish — no random mid-depth cartwheels or flight-instinct runs. This fish was big, and it wasn’t the least bit unnerved that its food was somehow fighting back. Strip-striking to set the hook — but not too hard, because bull trout have softer mouths than their cutthroat cousins — I stepped back a few feet into shallower water and prepared for a completely different experience. It took some time and some tight-line determination, but I did finally bring the big char to hand.

Bull trout are aptly named. They’re surly and their appearance matches their reputation. Years ago, they were reviled as trash fish that consumed the more “noble” cutthroats and rainbows of the Northwest. Today, they’re revered by most, protected under the Endangered Species Act and targeted by a cult following of fly anglers who understand that catching one means venturing into unspoiled places and being happy with maybe just a fish or two over the course of an outing.

They are special fish — the West’s only native char — and a true indicator species when it comes to everything from water quality, connectivity and general habitat health. In Idaho, unlike in neighboring Montana where they can only be legally targeted in a handful of waters, bull trout can be targeted, but they must immediately be returned to the water. Barbless hooks are a must to make the release as easy as possible.

The experience

By Wednesday evening, I’d been joined at the Spruce Tree Campground by a host of other campers and anglers, and fishing the river close to camp and along the river road became less appealing. As I noted, pullouts stretching some 20 miles downstream were regularly occupied, and, while I met some nice folks who’d ventured up the river to fish, this wasn’t what I was looking for.

So, on Thursday morning, Phoebe and I set off on foot along a trail that generally follows the river upstream from the campground. We gained quite a bit of elevation over the first mile or so and by the time we’d walked a good three miles, I was wondering if we’d ever find a trail down to the river that was accessible by anything other than mountain goats. Finally, after some more aimless hiking, I decided to clamber down what looked like a game trail from the hiking path several hundred feet to a willow-lined meadow through which the St. Joe flowed unmolested by other anglers.

It was a serious bushwhack, and we both took some scrapes and bumps on the way down to the meadow. Then, it was a soggy slog through tunnels of bright green, head-high willows to the river. We made it to the water with blood to show for it. The plan, I explained to my annoyed dog at the time, was to fish our way downstream to the campground and be fireside by dark, Irish whiskey in hand. And, generally speaking, that’s how it played out.

The river in this roadless stretch of the Panhandle National Forest is stunning, both in clarity and considering it’s backdrop — the Bitterroots loom in the distance. But it’s not the richest environment. Certainly, there were fish to be caught, but often, we’d walk several hundred yards between occupied habitat. I learned early on that the St. Joe’s cutthroats were pretty picky about where they’d congregate — they weren’t in the rapids or the shallows, and seemed to only show themselves when the water got deeper and in-stream structure, like downed wood or big rocks, provided a break in the river’s determined course. It makes sense, of course. Venturing into shallower water on a clear summer day is a surefire way to become lunch for an opportunistic osprey or bald eagle, both of which we’d seen over the course of our time on the river. These fish were all about security.

Once we deciphered where the fish were holding, we were able to move down the river at our own pace, stopping only to cast over water where cover gave fish some semblance of safety. And it was an effective plan. It seemed that each holding pool offered a couple of nice cutthroats before the racket put the other fish down. I cast a streamer for bull trout, but during the high sun of the afternoon, I didn’t get any takers.

Just as the sun started to slip behind the mountains to the west, the campground came into view. In all, we’d wandered maybe five or six miles and devoted about six hours to fishing. When Phoebe spied my truck and camper across the river, she didn’t waste any time — she plunged into the river and swam across. By the time I got to the camper to take off my wading boots, she was curled up under the awning, curled up in a hairy black ball, sound asleep.

The following day, with even more people descending on the upper St. Joe, we hopped in the truck and, using my dog-eared Idaho atlas and gazetteer, followed a sketchy logging road into the mountains, around the backside of Red Ives Peak and eventually to the St. Joe Lakes trailhead. Up this high, the river is but a creek, but we still found fish, albeit smaller cutthroats.

I love intimate, small-stream fishing, and while the fish weren’t as numerous or as big as they were farther downstream, this might have been my favorite day on the St. Joe. Near the end of the day, as I worked a beetle pattern over a deep seam, I just happened to look downstream about 100 yards. I noticed a significant disturbance in the river and realized that I was seeing the massive tail of a giant bull trout working its way upstream, hopefully to meet up with a spawning partner.

I reeled up the foam beetle, and Phoebe and I sat down on a streamside log and just watched as the fish pushed through current with determination — it finned through small rapids and around mid-stream rocks, making its way upriver. The water was so clear and so perfect that we could see the fish’s tell-tale white-tipped fins and even make out the bright orange spots along its flanks. The big char eventually topped a little swift-water rapid and it stopped mid-river, not 20 feet from the two of us. It might have been the largest bull trout I’d ever laid eyes on — I wouldn’t be surprised if it was 30 inches long.

At the very least, this giant fish had navigated to the river’s skinny upper reaches from dozens of miles downstream. It’s possible and not at all unlikely that this char even started it’s upstream migration weeks before, pushing up from the depths of Coeur d’Alene Lake more than 100 miles away only to arrive here at our feet. I’ve never won the lottery, but being able to intersect with this fish at this time and on this spot might be as close as I ever come.

The big bull trout rested for a good 10 minutes in the pool at our feet while Phoebe and I watched stoically from our log perch. Eventually, it regained its energy and moved farther up the little river, seeking out a mate and a redd to continue an age-old ritual that a lot of anglers tend to overlook. Phoebe and I … we marveled at the big fish and moved on, seeking out more feisty cutthroats that weren’t in the throes of their spawning run.

When, where and how

The St. Joe fishes well all summer long, starting in mid- to late June and continuing through September. West slope cutthroats are the predominant target species, but later in the summer, bull trout begin to show up as they start to move upriver for the fall spawn. Targeting bull trout in deep runs and pools is perfectly all right, so long as any fish caught are quickly and safely released. Most fly anglers frown on fishing to bull trout when they’re clearly moving onto redds or seeking mates for the annual spawn. These fish are listed as “threatened” under the federal Endangered Species Act, so it’s wise to treat any bull trout you encounter accordingly.

The lower St. Joe is pocked with private land holdings, but it can be fished, and fished well, from raft (it’s a popular white-water river, so fish it with the understanding that you’re going to see a lot of folks having a great deal of fun on the river). It’s upper reaches — starting somewhere above the Avery Depot — are great for walk-and-wade anglers, and the river’s cutthroats behave a lot like cutthroats anywhere else. At times they can be extremely gullible, and at others they can remain tight-lipped and finicky. But, generally speaking, if you find rising fish and if you can identify the hatch, you can catch these beautiful native fish.

At the start of summer, dependable caddis and mayfly hatches — the river boasts a great Green Drake hatch in late June and early July — should give anglers the opportunity to catch fish on top, but nymphs and even streamers work for the St. Joe’s cutthroats. Later in the year, as the weather warms and the wet season ends — usually by the middle of July or so — terrestrial bugs trailed by a nymph pattern can be deadly. I like to fish the St. Joe using beetle and ant patterns and I’ll often drop a size 14 Prince Nymph or a Girdle Bug under it. On good days, one or the other should work. For late-summer bull trout, big, gaudy streamers are the name of the game. Consider Zonkers, Slumpbusters and Muddler Minnows in sizes 4 to 8 — I have had good luck with yellow, orange and black streamers fished deep and slow through likely runs and stripped through holding pools.

Final word

Father Desmet was never canonized by the Catholic Church, and that’s likely because he wasn’t a typical priest back in his day. He was hardly the “contemplative” type, choosing instead to actively spread the Gospel and work on behalf of the West’s native peoples as conflicts with European Americans became increasingly common. He was a tireless advocate on behalf of native Americans, even as he worked to convert them to Catholicism. It’s likely that his ties to colonialism will prevent his canonization.

But, among fly fisher’s who’ve touched the bounty of the St. Joe River, Jeanne-Pierre Desmet might well be worthy of Godly recognition — his travels across the trout country of the West and Northwest likely inspired early outdoorsmen and women, and that some felt it worthwhile to name this panhandle river after Desmet’s first mission is quite telling.

After years of abuse and destruction at the hands of a greedy timber industry, the river is now largely recovered, and its fish are plentiful and vibrant. For some, the experience they offer is nothing short of spiritual.

Holy water, indeed.