Once thought genetically extinct, this native trout is on the path to recovery

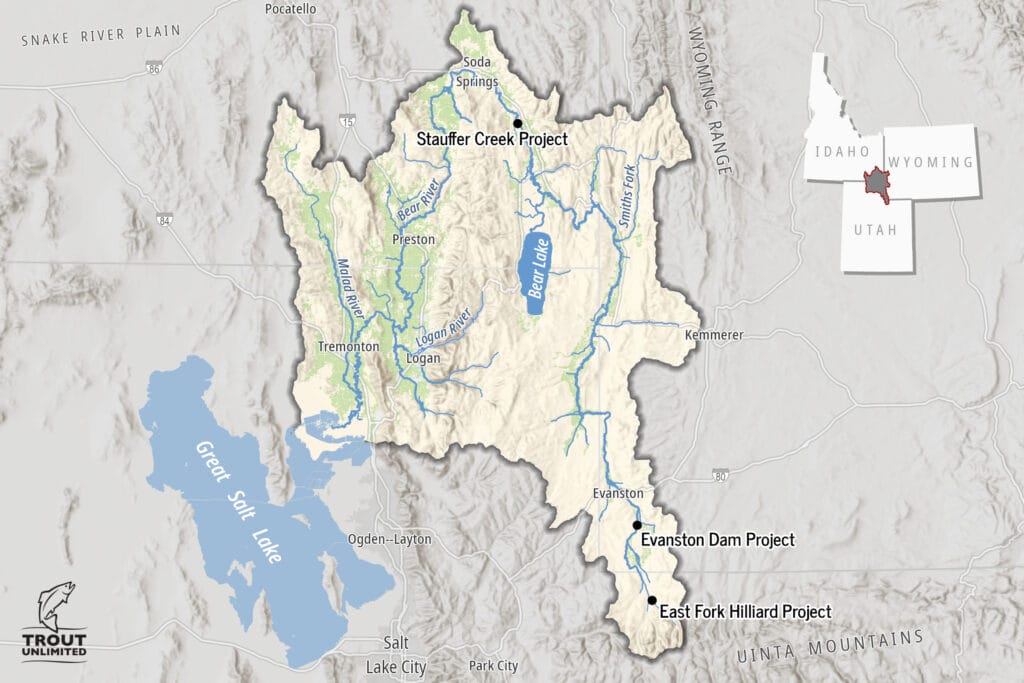

They call the Bear a “working river.” Covering more than 500 miles and tracing a broad horseshoe on its journey to the Great Salt Lake, the river connects rural ranching communities in Utah, Wyoming and Idaho. Its heavily controlled flows are interrupted along the way by major dams, seasonal diversions, and irrigation canals that siphon off water for agriculture and community supplies. Seasonal “push-up dams,” built during the growing season, create fish passage barriers and send plumes of sediment downstream when they are built or wash out.

In the face of all that, fisheries biologists thought by the middle of the last century that the river’s unique species of native trout, the Bear River cutthroat, had gone extinct. But these cutthroat trout have long been survivors, persisting in semi-arid watersheds that saw extreme floods and droughts, volcanic activity and river-redirecting lava flows over tens of thousands of years. These fish survived that tumult, and as it turned out, hung on in the face of multiple modern threats: heavy sediment loads, habitat fragmentation and competition with nonnative trout.

A new film by Trout Unlimited, “Reviving the Bear,” tells the story of the decades of work by numerous organizations, including TU, the Western Native Trout Initiative, federal and state agencies and local partners, to recover the Bear River cutthroat, while working closely with ranching communities on the river to ensure reliable—and often easier—access to the water they need to thrive.

Bear River cutthroat trout need free-flowing streams in which to migrate, spawn and find thermal refuge, especially in the face of climate change. Ranchers and communities along the river need reliable water supplies and have built networks of permanent and temporary dams and diversions to secure it.

But those needs can clash. During a fish movement study performed from 2011-2013, TU radio-tagged trout and worked with a high school class in Evanston, Wyo., to study them. The research showed that, where possible, fish migrated as many as 44 miles upstream into Utah headwaters to spawn, despite all the obstacles. Some 25 percent were entrained and lost in irrigation canals during or after spawning.

For more than two decades, TU’s on-the-ground staff have been offering win-win solutions to the dueling needs of fish and people on the Bear, one of 200+ Priority Waters where TU is focusing its conservation efforts. With private, state and federal funding—including recent critical investments from the Forest Service, Natural Resources Conservation Service, and the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service via the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law and Inflation Reduction Act—TU and partners have completed over a hundred projects that have reconnected, restored and rebuilt hundreds of miles on the Bear River and its tributaries. These projects remove barriers to migration, re-meander streams and enhance water quality.

In Bear Lake, where TU and partners have been reconnecting spawning tributaries, wild Bear River cutthroat trout now make up more than 60 percent of fish in the lake as compared to hatchery trout, up from just 10 percent two decades ago.

This work often makes life easier, cheaper and healthier for ranchers and local communities. Rather than drawing untreated water from an abandoned diversion, residents have newly drilled wells and a healthy, free-flowing river. Instead of building river-wide diversion dams every season with heavy machinery, ranchers may need only to open their headgate to access water or turn on new center-pivot sprinklers.

“They come in here and they changed the river up behind me and they planted trees,” said one Wyoming rancher, Wade Lowham, owner of Arrow Ranch, about a restoration project that allows him to access water without building a push-up dam on his property every year. “So far this year we haven’t had to do anything but raise the headgate up and lower it. It made my life a lot easier.”

And in the meantime, projects like these are improving fortunes for a native trout that has earned its reputation as a survivor—again.

Comments