These are strange and scary times. The yearning for a return to the normal is palpable.

I feel it too, even though the shelter-in-place orders affect me less than many, since I have worked from home for years. No question, this coronavirus business put me in a funk.

Fishing is a great funk reliever. But I haven’t been to a stream or the beach for weeks, trying to keep faith with the upshot of this fine essay by one of the leading voices of the angling community.

I find solace in photos, prompted by a phone whose IQ is twice that of mine.

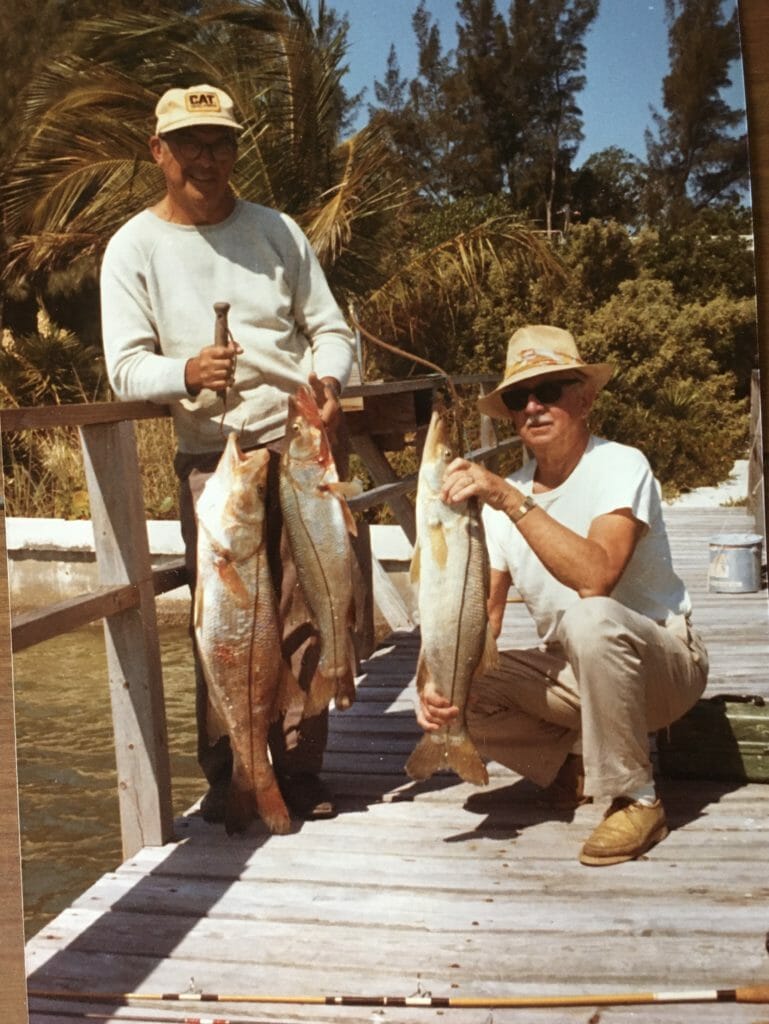

It was a photo of my grandfather that really kicked the funk’s arse. It was taken on the dock that connected his small retirement property to the Gulf of Mexico, where it embraces Florida’s Captiva Island. My grandfather and his best fishing buddy are posing with a triple-shot of hefty snook.

As I remember my grandfather, who had known a lot of hardship—he lost both parents as a child in the flu pandemic of 1918 and raised a family through the Great Depression—rarely smiled. In this photo a hint of a smile can be detected on his lips.

I learned how to fish largely from this man, whose mission whenever we visited became to get me and my brother into snook, one of the finest-eating fish of those waters. But we never did, at least not while he still lived. Plenty of jack crevalles, groupers, speckled sea trout. But never a snook.

I decided to show my grandfather some of the places where I’ve fished since, that he might appreciate how profound was the legacy of his instruction. So I took him on a tour of other photos residing on my Einsteinian phone.

Mostly we revisited places I’ve fished over the past year or two. And the people I’ve fished with. My grandfather, I think, believed that fishing, and the places where one can do it, and the people you do it with comfortably, have intrinsic value and are important, even in a time awash in loss, scarcity and fear.

I think he believed, as do I, that prominent among these important things are clean water, undeveloped open spaces and well-functioning habitat, so we may continue to enjoy the company of the many livings things that have evolved on this singular sphere with us.

But like toilet paper on grocery store shelves nowadays, these things are increasingly rare.

The conditions in which we live are constantly changing. Mostly this change happens slowly enough that we adapt without much injury or even notice. But this new coronavirus has an agenda all its own, and blinding speed is its cohort. Schedules, careers and expectations have been upended.

Given time, humans can and will adapt to this bellicose bug. That’s what life does: adapt to change. My grandfather went through plenty of difficult change and came through with at least a small reservoir of joy.

But some forms of life are so rarified, or their habitats so unique, they cannot adapt if change is too rapid. Trout and salmon, for all their variety and beauty—even Solomon in all his glory was not arrayed like one of these—are among the forms of wildlife most susceptible to rapid change.

The range of conditions in which salmonids thrive is narrow. And it’s narrower today than at any time since humans began trying to catch them with hook and line.

I for one do not wish to live in a world without trout. And, if we are even modestly sensible and strategic, we do not have to.

So the photos of the wondrous places where I have stepped in cold, clean water over the past year, and the people who have waded in those waters with me, inspire me not only to revisit them but also to redouble my efforts to keep them healthy and beautiful.

I’d like to do this, again, with other like-minded folks. You find whole battalions of them among Trout Unlimited chapters, sponsoring youth and veterans’ programs and on-the-ground habitat restoration and improvement projects.

So I know where to go to honor my grandfather in this way. Just as soon as these shelter-at-home orders are eased.

Sam Davidson is TU’s California/Oregon communications director. He lives near San Joaquin.

Do you have a story tell from days gone by? Or maybe a story of how you’re managing to stay connected to the rivers and the fish you love? Share it with us. We’d love to hear your “quarantine story.”