Efforts to fix habitat are as much for people as they are for the planet

It’s legislature season in New Mexico, a time I’ve come to abhor for how it represents my species and, perhaps more likely, my deficiencies as a chess player.

Sausage making is a circus, spectacular flights of ethical and logical acrobatics where people don’t always stick the landing. Sometimes it’s a gun fight, the cold pragmatism of shooting first (often in the back) and asking questions later. Politics reveal our worst selves or our true selves, which frequently are the same.

My consolation is knowing that when the niceties are laid aside, it is often so that truly important work can get done. From year to year in New Mexico, we alternate between 60- and 30-day sessions, the 30-day sessions focusing only on fiscal matters. In a short session like this year, the gloves can really come off, but it’s mainly just frantic.

I worked on a bill this year that aimed to create a trust to fund habitat restoration and conservation easements. The fund would be made up of oil and gas revenues, currently abundant though not expected to last. Ironic though it may seem to address environmental damage with treasure gained from environmental damage, we have a golden opportunity to make the best of the bad situation that is our unslakable thirst for petroleum.

Modeled after a Wyoming bill that created a trust with coal revenues, the New Mexico version would have enabled landscape-scale projects by leveraging state investment with federal dollars. It would have made ag land healthier and more productive, and promised greater economic security on tribal lands, land grants and in other rural communities.

The bill was so good, in fact, that it wasn’t good enough. To some this meant that its habitat purpose should have defined which habitat was better for restoration (public) and less so (private). And though a broad array of stakeholders had been enlisted as supporters, some key individuals felt left out (one legislator falsely claimed that certain broad categories of folks were an afterthought). To others, the bill was a wagon onto which any decent conservation initiative should have been piled, regardless of how heavy or unwieldy.

Although it fizzled in the end, the chances for passing a trust-fund bill in the future look promising, with more voices at the table and a chance to trim some of the fat that made it into this year’s attempt. There’s plenty of reason for optimism, yet it’s difficult to stomach that after so much work we’re seemingly back to the zero.

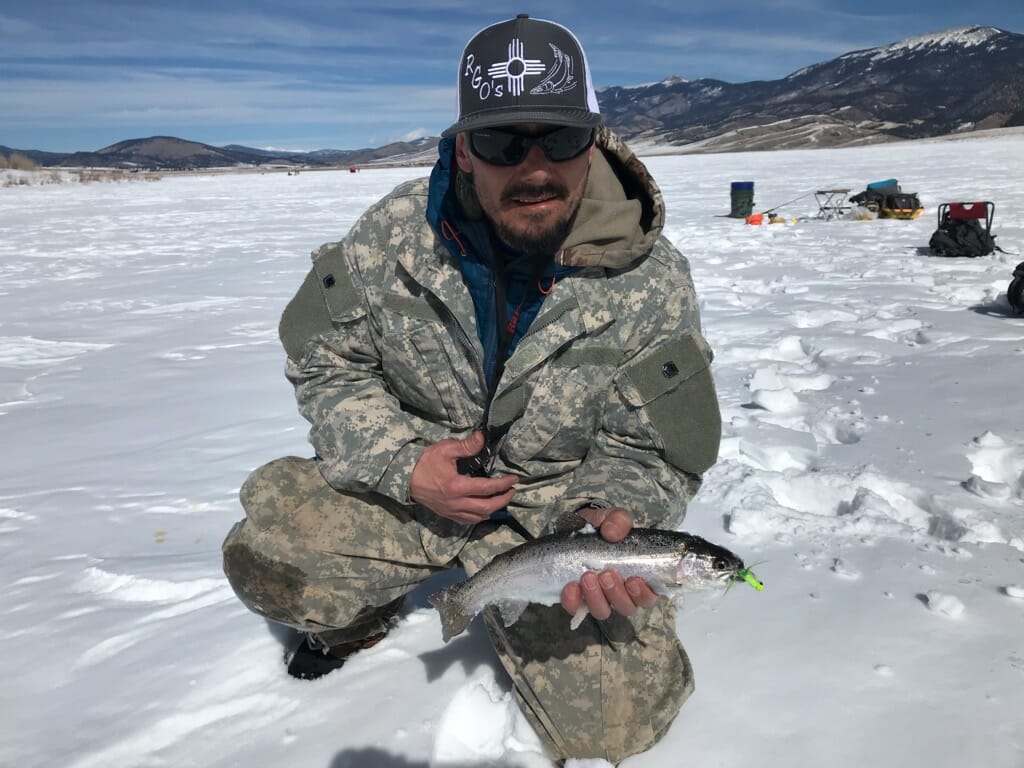

The ice fishing scene at Eagle Nest Lake tempts me to believe that the world is all ours. We fill the manicured parking lot and use the vault toilet. We haul our sleds — piled Grinch-style with chairs, augers, coolers of beer and lunch goodies, wind shelters, and fishing rods — onto the frozen white flat. Our brined and often petroleum-based bait stains our fingers as we take it from manufactured glass jars and thread it onto forged metal hooks with which we catch fish species transplanted here from distant native habitats. At day’s end, we thaw fingers before our car heaters, then watch the sun go from white to pink in the time it takes to combust a few gallons of gasoline.

The truth, of course, is that it is we who dance to the earth’s music instead of the other way around. As it has always been, when the salmon come, the bears and gulls come too.

Eagles, mink, and people spread the wealth from the rivers, feeding the earth as they traipse across her.

Same in Africa with the great wildlife migrations, the zebras crossing rivers keep crocodiles alive. At Eagle Nest, winter is more than a time of predation. In the blue late-day shade, it’s protein sledding landward, a movement of organic resources from one place to another. The ravens understand even if this escapes our notice. Even before we’re gone, they hop and fly across the ice eating the fish guts we’ve left there. At a time when a human being can’t seem to draw a breath without impacting the environment, it’s somehow helpful to consider that the success or failure of a piece of legislation won’t knock the earth out of orbit for even a second.

Even if our bill passed and the money were available tomorrow (it wouldn’t be), the earth would still be on its own schedule in terms of fixing itself. That’s the simple fact. Habitat restoration is for our own survival, in the human time frame, however long — or short — we choose to make it.

Toner Mitchell is Trout Unlimited’s water and habitat coordinator in New Mexico. He lives and works in Santa Fe.