I get asked this question “off the record” all the time. What’s the very best thing you can give as a gift to someone who really digs fly fishing?

There is, of course, no simple answer. Everyone’s budget is different. Ever angler’s skill level is different, and so on…

After a slap of the forehead, I realized, however, that if I’m being perfectly honest there’s really one clear answer to this question:

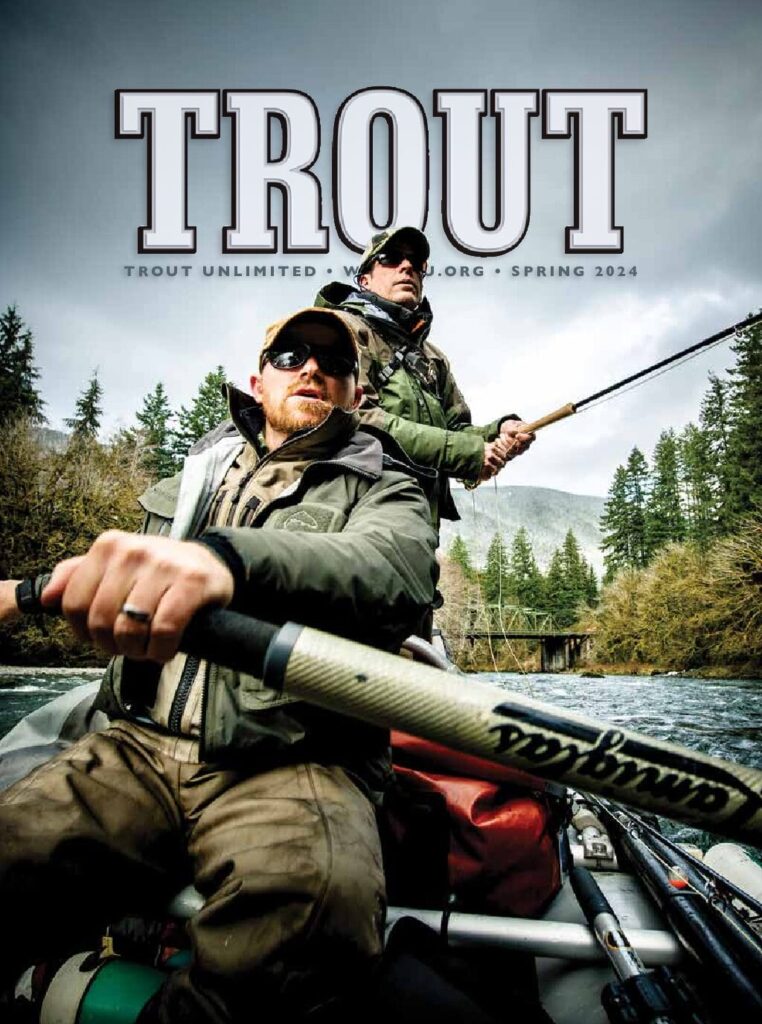

TROUT magazine!

I promise, it’s worth it

Sure, I’m biased. I’m the editor, but I believe in my team, the work we do and the product we produce. And I challenge you to find a better value, with a more lasting, meaningful impact, that also mixes in healthy doses of ethos and cause.

TROUT is the conscience of trout fishing in America. If you want to learn how to be a better angler, check… we do that. Want to be entertained by great writing and beautiful images? Covered. How about getting behind the causes and the organization that largely makes fishing possible in the first place? Of course. And by seeing which companies advertise, you see which ones actually care about conservation.

Readers who dive into TROUT magazine’s 100 pages every quarter cannot help but become more “complete” anglers in the spirit Izaak Walton intended nearly 400 years ago.

What’s to come

And I can tell you that the next four issues are going to be haymakers… the best we’ve ever done.

December carries a theme of “innovation,” and not as that relates just to fishing gear, but also conservation.

March is “Storytellers” and it’s there where you’ll find the last essay ever published by the late, great John Gierach.

June has a theme of “Bugs,” which runs the gamut of everything from hatch matching and the flies to pull that off, to addressing the riddle of why we’re not seeing insects quite like we used to.

And September 2026 is all about “Fishing Karma,” of which you will have plenty if you sign up for TROUT.

$35… best deal in fishing. Skills and ethos to last a lifetime. If you already get it, give it to someone else you care about. I will be supremely grateful. And you won’t be disappointed. I promise.