Those who care about the imperiled Snake River salmon and steelhead need to speak up on their behalf—now—said Nez Perce Vice Chairman Shannon Wheeler and U.S. Rep. Mike Simpson (R-ID) this week during a special “Trout Week” event with Trout Unlimited CEO Chris Wood.

“The Nez Perce are charged with honoring our ancient covenant that we have with the salmon,” Wheeler said. “They give themselves to us in our beginnings and in our stories. And when they lost their voice, we were to become their voice. And now is the time, especially now, that we have to be their voice.”

Simpson, who has been reading a book called Change: How to Make Big Things Happen, said that we have much more work to do to build public support for removing the dams to recover the Snake River fisheries. He urged supporters to help increase pressure on decision makers in the Pacific Northwest, especially using their social media networks.

“We’ve got to create a snowball effect,” Simpson said. “We’ve got to grow the conversation and convince people that this is the right thing to do.”

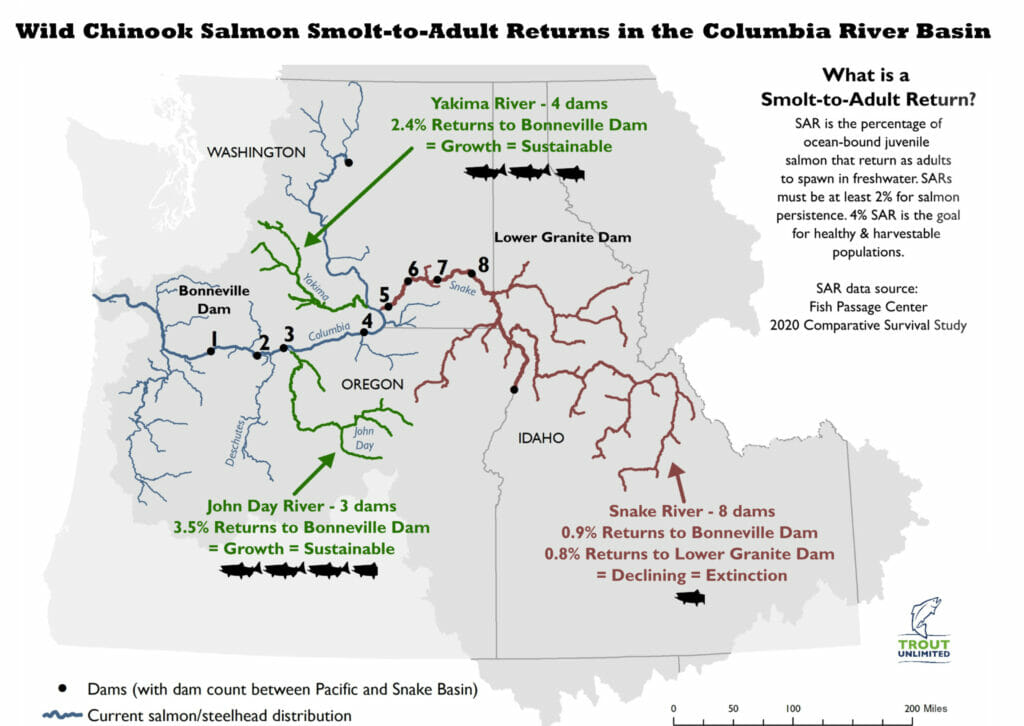

Historically, millions of salmon and steelhead returned annually to spawn in the vast and pristine waters of the Snake River basin in Idaho. These salmon and steelhead travel further and climb higher than any other anadromous fish in the world. Unfortunately, these runs have all but collapsed since the construction of the four lower Snake dams beginning in the 1960s.

The dams create hot, slack water in 140 miles of reservoirs, and the turbines themselves are a literal deathtrap for the smolts migrating out to sea, destroying the bulk of the salmon run before the juveniles even reach the ocean.

The Snake River basin holds half of all remaining coldwater habitat for salmon and steelhead in the lower 48, a percentage that is likely to increase to 65 percent as climate change warms lower-elevation waters.

North Idaho TU field coordinator Eric Crawford noted that the portion of the Snake River Basin that contains anadromous fish species is roughly 49,000 square miles—more than the states of New Jersey, Vermont, New Hampshire, Massachusetts, Connecticut, and Rhode Island combined.

Simpson, who released his Columbia Basin Initiative proposal in February, committed to drafting legislation to remove the dams, invest billions in Northwest infrastructure, and embark on what would be the largest restoration initiative in the world.

“The issue of dams and recovery of Snake River salmon has been an issue in Idaho for 50 years,” Simpson said. “We are going to have to look at things different in the Northwest. People ask me, ‘Why do you want to disrupt a system that’s working?’ I say, ‘Working for who?’ It’s not working if you are salmon, because they are going extinct.

“I don’t think we’re going to allow that to happen,” he added. “I don’t think we should allow that to happen.”

The benefits of the dams, including barging and a small amount of hydro-electricity, would be replaced with new infrastructure under the Simpson plan. The benefits of a free-flowing river, especially to salmon, cannot be replaced or mitigated. We know this from 50 years of trying every other option.

TU Senior Scientist Helen Neville noted returns are in dire straits with most populations at historic lows.

“Still, I think the one thing that we have to remember and be inspired and amazed by is the resilience of these fish.” Pacific salmon, she noted, “evolved in a landscape over millions of years. They have suffered volcanoes, landslides, fires, floods, and they have strategies to deal with that with their diverse life histories. But the problem is their strategies depend on a connected system and the ability to access different habitats at different times. We’ve kind of taken away their main coping mechanism and being able to function like that. They are amazingly resilient, but they’re really literally hitting up against these concrete structures.”

The Nez Perce, along with other tribes in the Northwest, signed treaties negotiated with the U.S. government and ratified by Congress that guaranteed them the right to fish for salmon in exchange for ceding claim to 12 million acres of land.

But Wheeler lauded the Simpson proposal and said that it is the best path forward for all parties: “Congressman Simpson’s approach is actually the true fix for this.”

Kayeloni Scott, a Spokane Tribal member, Nez Perce descendant and spokesperson for the Tribe, pointed out that the Nez Perce have been doing the work of restoration across the basin and that they are just waiting for the fish to come back. She said that they will continue fighting for the salmon.

Simpson lauded that effort .

“Without the work that the tribes have done over the last 25 or 30 years, salmon would be extinct today,” he said. “The reason we’re able to discuss this today and how we’re going to save the salmon is because the work that’s tribes have done and they deserve the credit for that,” Simpson said.

Simpson said he firmly believes the lower four Snake River dams will be removed eventually. “But make no mistake about it, if you don’t remove these dams these fish will go extinct.”

Greg McReynolds, based in Idaho, is TU’s Snake River campaign director.