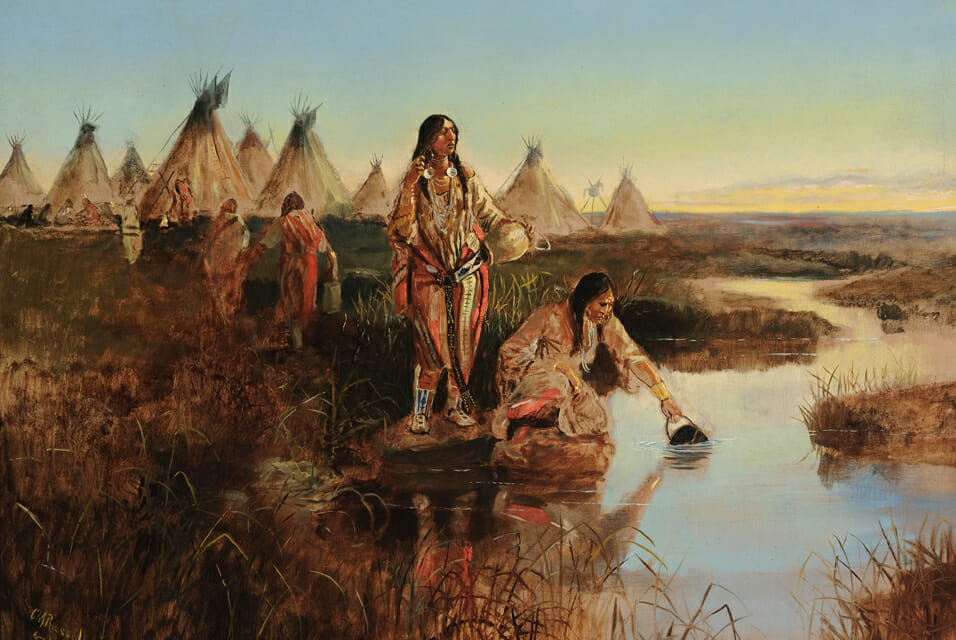

Water for Camp, watercolor, Charlie Russell. Source: Wikipedia

By Tom Reed

It is wide open terrain, a landscape that leaves no question as to where Montana got its nickname: Big Sky Country. This is the land of Charlie Russell. He was the quintessential artist of the Old West, a talent who told stories in watercolor and oil. This topography—the Judith—was his muse.

The Rockies meet the Great Plains here near Lewistown, Mont., the beating heart of the fourth largest state in the union and it is no great stretch of the imagination to see what Russell saw when he rode onto a ranch as a 16- year-old kid around 1880. North and a bit east of town, the Judith Mountains themselves rise to the skyline, clad in ponderosa and Doug fir, the canyons lush and rich with alder and birch, slender streams birthing cold, clean water on their way to the mighty, fabled Missouri.

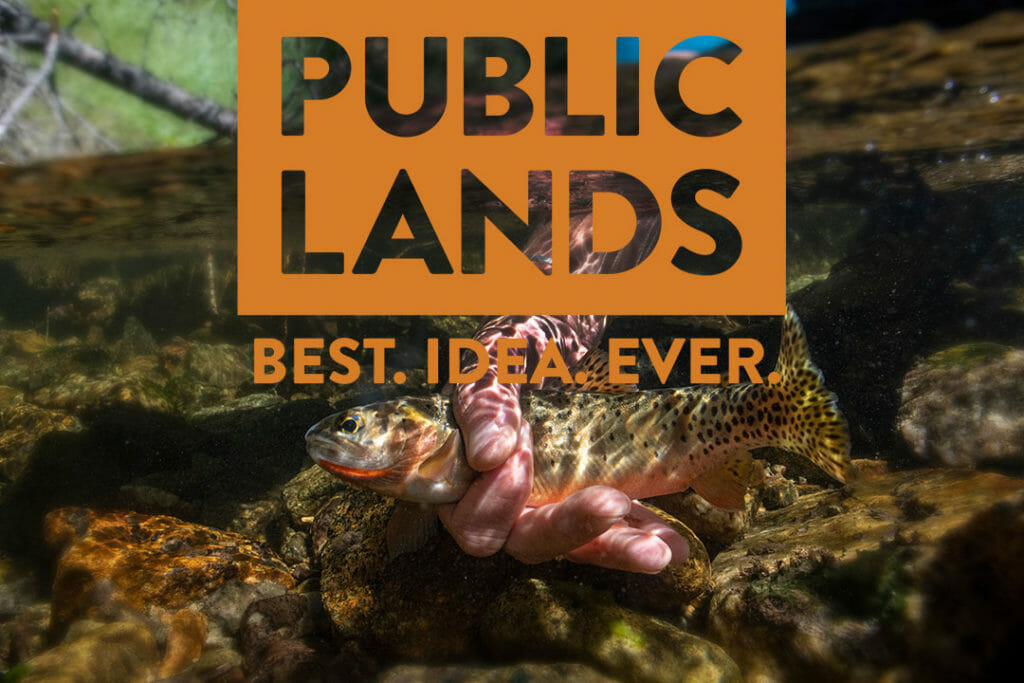

Here, in a tiny stream swim the eastern-most population of westslope cutthroat trout, one of Montana’s few native coldwater salmonids and it was here that we embarked on a late summer expedition to its depths, visions of Russell watercolors never far from the imagination.

We dropped down a trail that Russell himself may have been ridden as a daredevil–a horseback into a canyon choked with Doug fir, mountain maple and birch to the stream that a child could hop across in one bound. A hand went to the water and felt its chill.

We turned downstream following the water as it built, scrambling over deadfall, swinging a fly on thin tippet into holes not much larger that a cowboy hat turned upside down on the kitchen table. If we were not careful, we saw flashes of shadow as little cutthroat squirted for cover at our step. But if we were cautious, camouflaged behind tree limb and brush, we might entice a tiny trout from a tiny pocket, hold it in our hand, admire its purity and return it to the water as quick as one might read this sentence.

These fish are rare, few and genetically pure as they have been isolated in this tiny stream from other non-native fish like rainbow trout and brookies as long as time itself.

We caught only a few, scared many more, and sat for a time on the banks of a little stream on the far eastern edge of the native range of Montana’s trout, reflecting on its future. Today, the land managers who salaries we pay to manage our land—the Bureau of Land Management—is eyeing this stream and other critical habitats, called Areas of Critical Environmental Concern/Outstanding Natural Areas (ACEC) for possible oil and gas exploration.

In all, these folks want to do away with all protections that the ACEC designation affords on all lands so designated. Consider that only 3 percent of the BLM ground in Charlie Russell country has this designation and you begin to understand the extent of the problem. In the case of this tiny stream with its little cutthroat trout, we’re only talking 1,500 acres out of 650,000.

Some may say that a few little fish swimming in an obscure mountain range in the heart of Montana are expendable for energy production in our mighty nation. But others would say if we cannot protect Charlie Russell’s cutthroat, only one little stream, of what measure of good are our museums with their great works of art, our concert halls and the great man-made monuments in our cities? Maybe someday, long in the future, another 16-year-old kid might come to this little corner of the world with a fly rod in one hand and a head full of imagination about what our public land once was and still is.

The bison and bighorn sheep of days of Russell are gone, gone with the travois, the hide tepee, the Winchester repeating rifles and the cattle drives. But this little fish, Charlie Russell’s fish, is still here. Write to Dan Brunkhorst, Lewistown RMP Project Manager, 920 NE Main St., Lewistown, MT 59457, (406) 538-1981, dbrunkho@blm.gov

Let the BLM know that ACEC designations should not be lifted in the new resource management plan he and our other employees are working on.

Tom Reed is Northern Rockies director for TU’s Sportsmen’s Conservation Project. He lives and works near Ennis, Mont.