TU’s Jake Lemon sees promise in a stream anglers breeze past to get to the Pere Marquette

Jake Lemon admits he was as guilty as most when it came to paying attention to Michigan’s White River.

“It’s basically sandwiched between the Muskegon and the Pere Marquette,” Lemon said of the White. “Many people just drive right by it on their way to the more popular rivers.”

Eventually, he realized that he was missing some opportunities — not only to fish in the White, but to investigate ways to improve the river’s water quality, fishery and other recreational opportunities.

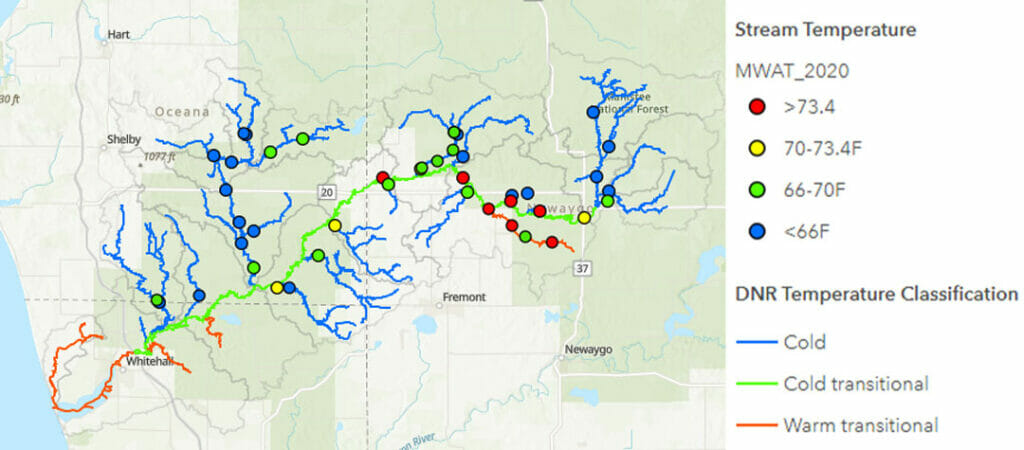

The White River flows 83 miles southwest from its source near Big Rapids to White Lake, a drowned river mouth on Lake Michigan. The headwaters of its South Branch support healthy populations of brown trout and brook trout. Below the dam in Hesperia, steelhead and salmon run. The North Branch, while smaller than the South Branch, also supports quality coldwater fish.

“It piqued my interest because there are sections of the watershed that feature high-quality coldwater habitat,” said Lemon, a Michigan resident who serves as TU’s monitoring and community science manager. “But there are other sections where there has been significant impact, whether from dams, agriculture or a lot of riparian development.”

Since the river drew Lemon’s focus, he has launched a restoration effort in the watershed thanks to support from the Fremont Area Community Foundation, which has awarded TU grants to continue stakeholder organizing and to study the watershed in hopes of future restoration projects.

In his job coordinating TU’s community science and monitoring efforts, Lemon is spread far and wide.

“I kind of flit around dabble in watersheds all over the place,” said Lemon, who has headed major community science efforts in many states beyond Michigan, including Pennsylvania, Virginia and West Virginia. “I’ve really been wanting to sink my teeth into a specific watershed for years.”

The White made sense.

“There is a lot of latent energy within the community,” Lemon said. “But there wasn’t really anyone driving the train.”

Lemon started doing some basic work in the watershed.

“Where I had the opportunity, I started redirecting some projects to the White,” Lemon said.

That included a major water temperature study that was already ongoing within the Huron-Manistee National Forest, though part of which the White River flows. He also trained more than two-dozen volunteers how to use TU’s RIVERS app to survey the watershed for potential issues, including habitat degradation and barriers.

“That helped me collect useful information, but just as importantly it helped me to get to know people in the area,” Lemon said.

A small initial grant from the Fremont Area Community Foundation allowed Lemon to convene a local stakeholder group to gauge citizen interest in a 3- top 5-year focus on the river.

“We did a lot of outreach and pulled together a consensus workshop with disparate groups,” Lemon said.

Charles Chandler of White Cloud was among those who were invited to participate in the stakeholder group.

“The beauty and recreational opportunity the White River could provide are unrealized,” said Chandler, a 79-year-old who relocated to Michigan from Texas in 2006. “In 2014 a small group of supporters, fishermen and kayakers met and began advocating for improving the recreational opportunities on the river.”

Part of the effort was clearing a path through fallen trees to allow for canoe and kayak passage while leaving the bulk of the wood for habitat.

“As our small group maintained this water trail we also developed signage and maps, and improved launches,” Chandler said.

Lemon’s involvement has helped to further mobilize what has been deemed the White River Watershed Collaborative.

After convening the first stakeholder effort, Lemon was able to leverage that initial grant into a larger award that will allow him and partners to dig deeper into potential projects.

One possible project has Lemon especially excited. Water pooled behind a small dam in the city of White Cloud warms up significantly in the summer. While the river above the small lake is high quality and home to wild brown and brook trout, the water below the dam is about 10 degrees warmer. The dam is degrading and requires significant annual maintenance funding. Lemon and others are working with the City of White Cloud to understand and evaluate dam removal as they wrestle with what to do with their aging dam.

“If you remove that dam, you’re talking about significantly cooling up to 30 miles of downstream trout habitat,” Lemon said. “It would be transformational.”

Which leads to another thing that Lemon and stakeholders are examining — the economic possibilities.

“We are confident that restoration work can improve fishing, boating and other recreation opportunities,” Lemon said. “It would be great to get to a point where anglers are mentioning the White in the same breath as the PM, Muskegon and other premier Michigan fisheries.”