Lead can poison loons and eagles, but we can choose fly tying alternatives.

“I fish mainly because I love the environs where trout are found,” wrote Robert Traver in the preface to his classic book, Trout Madness.

The passage came to mind this summer as I paddled my canoe across the lake back to my family’s cottage in the western Upper Peninsula of Michigan with a freshly caught northern pike in my net for the day’s lunch. The early-morning mist was just starting to dissipate, the water a deep, cadet blue, and the shoreline was ringed by bright paperbark birches amidst shoreline cedars under towering white pines.

Bald eagles perch regularly in one of the white pines near our cottage and have since I was a kid even when I rarely saw them anywhere else. A pair of loons have similarly occupied the lake since; waking me up at dawn with their wailing calls when I slept on the enclosed front porch facing the lake. My four-year-old son, on his first trip to the cottage this summer, began imitating the loon calls with surprising accuracy.

It was one of those loons which sparked my recall of the Traver passage when it surfaced just about a dozen yards from my canoe. I try to give them space, but they can certainly fish near me if they wish. A little farther out on the other side of the canoe, its partner called out its searching wail.

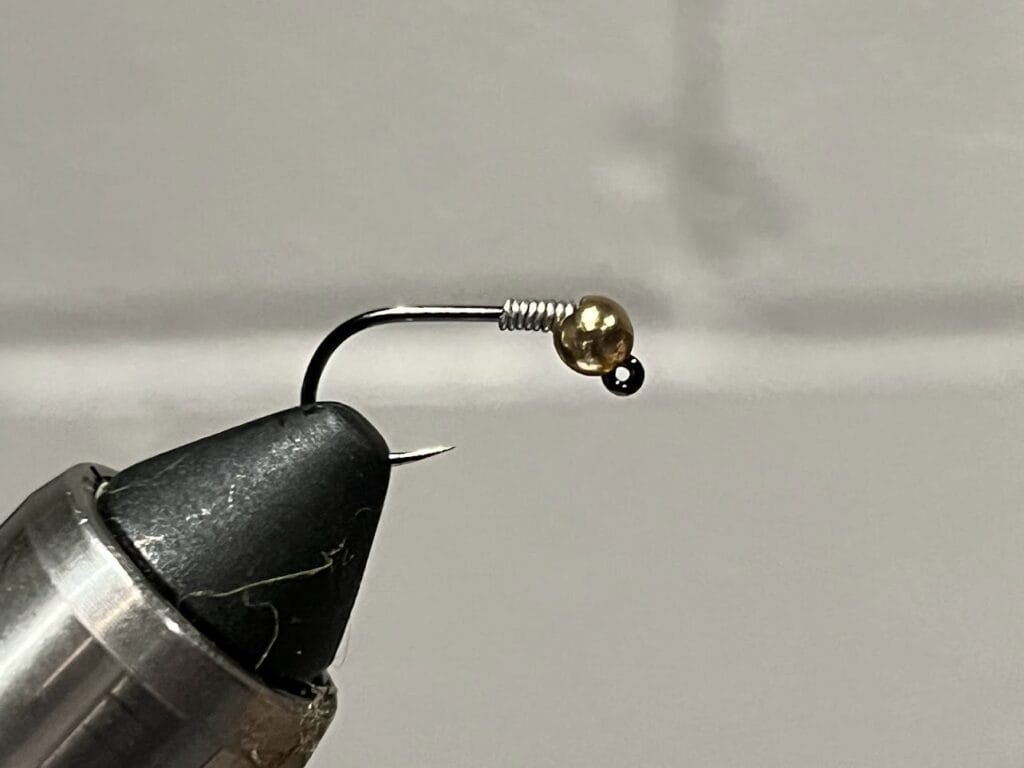

They dove and surfaced along either side of me as I paddled, and I felt proud that I caught the northern pike using nonlead alternatives to traditional lead fly tying materials: on a red and white Pike Bunny jig I tied with tungsten dumbbell eyes, trolled off my 11wt on a sinking line behind the canoe.

Impacts of Lead on Wildlife

Lead is a toxin that is harmful to humans and often fatal to some wildlife, especially common loons and bald eagles. Multiple studies have linked an impact on the population growth rate from lead poisoning to common loons (primarily from lead fishing tackle) and bald eagles (primarily from lead ammunition, but on our lake, they eat plenty of fish, too). Thinking about these environs – as Traver put it – is part of why I started tying flies a few years ago: to be sure that, whether stripping in a streamer for northern pike or drifting a nymph through a pool in the surrounding streams for brookies, no lost fly of mine would ever poison a loon or an eagle.

None of us ties flies with the intention of losing them, but I doubt any of us realistically thinks we never will. Especially here in Michigan, it’s a rare trout stream lacking a wall of fly-stealing foliage ready to snag your backcast. Nymphs ticked on the bottom get caught on submerged logs and lines break with streamers attached. Sometimes fish fight a little too hard and sometimes our knots just aren’t strong enough to survive that imperfect snap cast. We lose flies, and if they contain lead, they pose a risk to a loon that might scoop it off the bottom mistaken for pebbles used to grind food in its gullet or by a bald eagle consuming a fish with the broken off Clouser stuck in its lip.

Nonlead Fly Tying Alternatives

There are some simple ways, however, to keep additional lead out of our waters by choosing, as individuals, to tie our flies with nonlead materials substituting for lead wire, lead dumbbell eyes, cones or bead-heads, and lead split shot.

Neall Dollhopf manages my local fly shop, The Painted Trout, in Dexter, Michigan. He stocks exclusively nonlead fly tying materials, which makes it easy for me to buy only these ingredients for my bench. I asked him why he made that choice as a business.

“To me, it’s kind of obvious. Lead is bad, everybody knows it’s bad, so there’s no reason to have it when we have products available like tungsten and brass.”

In fly tying, the primary places where lead is traditionally used are in lead wire and lead weights.

“Everyone’s really familiar with lead wire when we’re wrapping the shanks of our flies to get them down, but it’s a real easy substitute to grab a roll of lead-free wire,” Dollhopf said. “It’s even a little bit tougher, not quite as easy to tear.”

If you’re used to tying with lead wire, he recommends using a couple extra wraps with the nonlead wire or moving up a size to achieve the same weight as the lead wire; nonlead wire, made from an alloy, can be about 60% of the weight of lead wire for the same diameter.

“And then any sort of other weight – cones, dumbbell eyes, bead heads – anything that you can get in lead, we have here in tungsten,” added Dollhopf. “It’s easier than most people think, it’s just a little more expensive than lead, but it’s worth it.”

For tungsten substitutes, because it is so dense, Dollhopf doesn’t make any size adjustments compared to lead.

“I don’t find any noticeable difference in performance, so I just go same for same. And the fish still eat it.”

On the water, anglers can replace lead split shot with tin split shot or tungsten putty, as well as using sinking lines and leaders as appropriate to get flies deeper.

For me, it’s easy to tie without lead because I simply never stock my bench with any lead materials. I fish mostly my own flies, and while I regret losing flies for both the time that I put into tying them and because I hate to leave anything behind on the waters I fish, I can be certain – through individual choice – that I’m protecting the loons and eagles from poisoning through my actions and choices.

I hope you’ll consider making the same choice. When you hear the loons calling, or a bald eagle tip its wing as it soars above you as you fish, you might just imagine that they’re thanking you.