A Colorado River cutthroat landed in Colorado. Daniel A. Ritz photo.

Progress and discovery alive and well in the center of the fly fishing universe

Daniel Ritz is fishing across the Western United States this summer in an attempt to reach the Master Caster class of the Western Native Trout Challenge, attempting to land each of the 20 native trout species in their historical ranges of the 12 states in the West. You can follow Ritz as he travels across the West by following Trout Unlimited, Orvis, Western Native Trout Challenge and Montana Fly Company on social media using #WesternTroutChallenge.

After completing both the Wyoming Cutt-Slam and the Utah Cutthroat Slam, I was excited to spend some time in a new place focusing my attention on one species.

Initially, I must admit, Colorado was not one of the legs of this trip I was the most excited about. In my totally outsider experience — which I am sure Coloradans are just fine with — Colorado has the eminence of a mecca and central location for all things western fly fishing. Having never fished in Colorado, all I knew for sure was that there were a lot of Gold Medal blue ribbon fisheries and even more anglers — new and old — that frequent them. I have always found myself hesitant to head to the “best of” places. Just not my style.

So, of course, I decided to head to southern Colorado over the Fourth of July weekend.

I arrived in Durango on a Friday afternoon. I checked in with family and friends before attempting to successfully disappear into the San Juan National Forest north of town in do-it-yourself style for the weekend. My goal was to experience a few days of fishing for Colorado River cutthroat trout on the abundant public lands before meeting and fishing with Ty Churchwell of Trout Unlimited. It felt irresponsible to not have any experience at all in Colorado waters before meeting with a man who later described Durango as “the center of the universe.”

Initially, I found myself at a Forest Service campground just outside Durango where I sweet talked the camp host to let me explore the river before deciding if I was going to stay or not.

Completely unaware of the locations of the revered Colorado River cutthroat trout of Hermosa Creek, it wasn’t long before I was hucking it over a ledge and into the deep canyon of the lower creek. Let my eagerness serve as a lesson — it is a lot easier to dig your grave than get out of it. While it only took 45 minutes or so to descend the nearly 1,000-foot valley, it took nearly two hours to get back to the surface. Furthermore, I never even reached the river due to a sheer cliff only 100 or so feet from the bottom.

Frustrated, I tried a bit further up the river the next day. After a nearly 10-mile hike and a number of dicey cattle encounters (eyes up, people), I was again disappointed to find myself in a section of river that simply put, didn’t feel “fishy” and produced no fish.

By now you may be wondering why I was so focused on this particular river system.

Hermosa Creek and the Colorado River cutthroat trout within it may be one of the most remarkable conservation stories I have ever heard.

Churchwell, then working as the San Juan Mountains coordinator for Trout Unlimited in Colorado, helped create the Hermosa Creek River Protection Work Group in 2008 with the goal to consider protections for the creek, including a Wild and Scenic River designation and possible public land protection mechanisms — including a wilderness space within the Hermosa Creek drainage. To do this, Churchwell and his partners reached out to a wide breadth of local and regional community members for participation in the workgroup.

“It’s all about collaboration and compromise,” said Churchwell, now serving as the mining coordinator for Trout Unlimited’s Angler Conservation Program. “We wanted, when we presented our bill, to be sure that everyone was behind it and that all constituency groups got a win for their specific values. Everyone had a seat at the table, and no one group’s values were any more important than the other’s.”

Acts like this require congressional approval, and the team’s goal was to ensure the entirety of the constituency was behind the proposed plan to minimize wiggle room from any opposition.

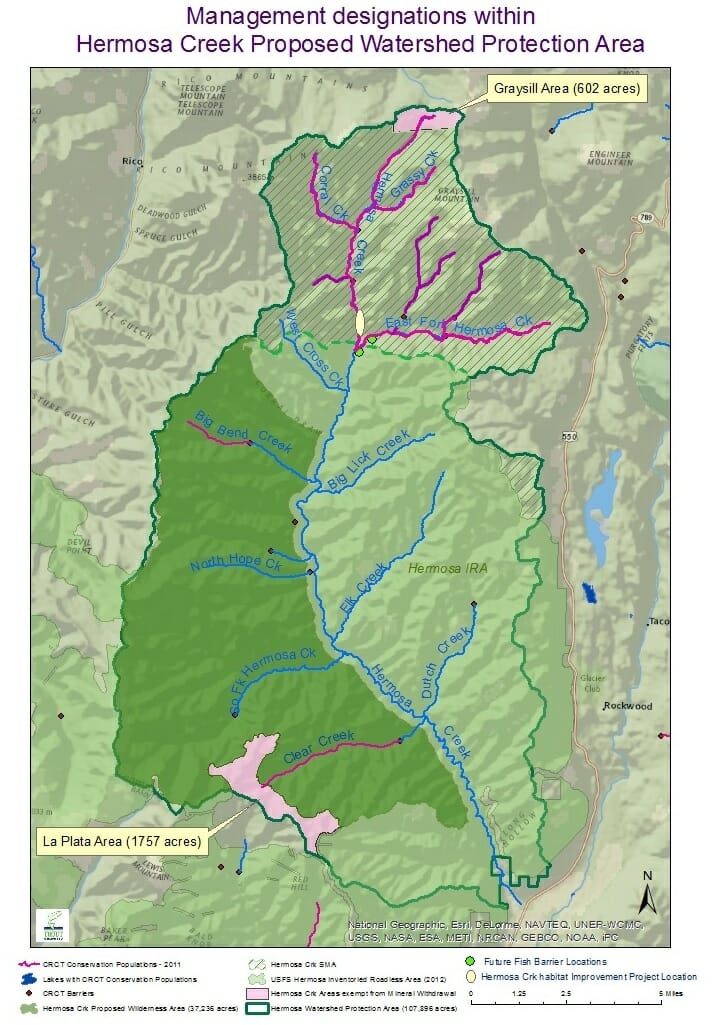

The bill, submitted to Congress in 2011, comprised a Special Management Area for the entire Hermosa Creek drainage, the first of its kind. While Trout Unlimited and Churchwell were focused on preserving Hermosa Creek as a native trout stream — work had already begun to reestablish Colorado River cutthroats as early in 1991 by Colorado Parks and Wildlife — he ensured the key to the Hermosa Creek Wilderness campaign’s success was being sure all stakeholders were recognized and made whole.

“We didn’t go in asking for the entire area to be marked as wilderness,” Churchwell explained. “The most important parts were wilderness, but any mountain bike trail miles that were lost (two trails) and any impacts to other user group areas were mitigated where possible.”

So, the group advocated for wilderness on the west half of the Hermosa Basin — where two remnant populations of Colorado River cutthroat trout were hanging on — and just half of the roadless area on the east side of the basin to appease all interested parties.

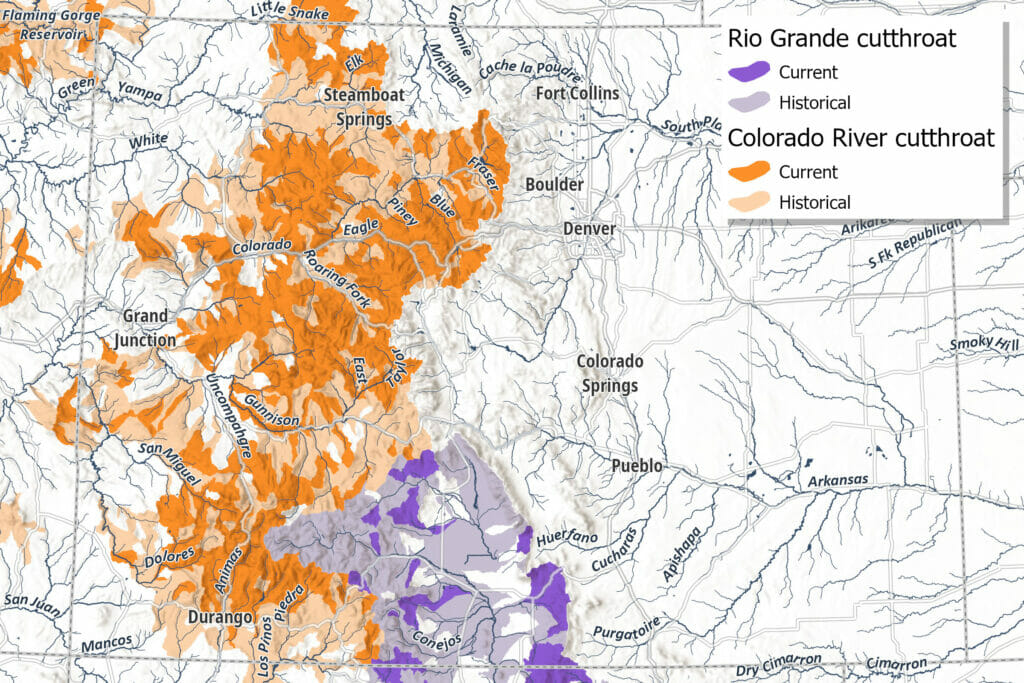

The Hermosa Creek Watershed Protection Act was signed into law in 2014 by President Barack Obama. Four years after the passage of the Hermosa Creek protection legislation, biologists discovered there were actually two unique populations of Colorado River cutthroat trout in the system: the rare San Juan lineage and the lineage historically emanating from the upper Colorado and Green rivers. Speaking in geologic time, these two lineages would have been separated by what is today Lake Powell and the Glen Canyon, but are are part of the broader Colorado River system.

Editor’s Note: Check out the story below for details about how a trip to Smithsonian helped biologists identify surviving San Juan lineage cutthroat trout.

As it happens, two waterfalls on the tributaries in the Hermosa Creek wilderness had sequestered the rare trout above possible invasion from non-natives downstream. Months after the discovery of the ancient lineage the population was threatened by the 416 Fire.

By pack mule and on foot, the Forest Service and Colorado Parks and Wildlife members went in to save the previously thought-to-be extinct lineage. Less than 100 individual trout were removed and taken to the Durango fish hatchery for safekeeping and possible brood stock development.

Today, independent of the naturally occurring San Juan Lineage in tributaries in the new wilderness, a variety of artificial barriers within the Colorado Parks and Wildlife reintroduction area ensure the upper portion of the main stem of Hermosa Creek remains an exclusive Colorado River cutthroat trout fishery, but just not the San Juan lineage.

But where were they? After two and a half days of exploration I was yet to find anything remotely close to one of the revered Colorado River cutthroats.

So, as everyone should, I went to the local fly shop.

Covered in mud, sweat and likely blood, I walked through the doors of Duranglers Flies and Supplies in downtown Durango and sheepishly asked what I was doing wrong.

“Don’t get me wrong. I’m putting in the miles. I’m not asking for a handout,” I said in an attempt to save face. “But something tells me it shouldn’t be this hard.”

A young man chuckled when I told him of my weekend trials and proceeded to let me know I had gone within a half a mile of the first barrier with the vaunted Colorado River cutthroat above it.

The next morning I was joined by Churchwell and Kara Armano, TU’s southwest director of communications. I hoped to finally experience what is widely considered one of the most beautiful cutthroat of the West.

After a nearly one-hour long ride deep into the Upper Hermosa drainage, we hopped out of our trucks just upstream from an artificial barrier creating a waterfall scale plunge pool.

It wasn’t long before each of us started connecting with small, beautiful trout in frigid waters that turned our feet into bricks.

Colorado River cutthroat trout have an incredible color scheme. There were fish with pale green backs, some with yellowish almost orange bellies, but the most remarkable feature was their intense orange gill plates.

“The other weekend, my husband and I easily had a 100 fish day up here,” Armano shared. “It’s incredible to know that these fish are back where they belong.”

Armano strongly emphasized that Colorado is a key headwater state – supplying water to 17 downstream states — and it was essential that Coloradans remain focused on the health of their rivers as they greatly influence river systems downstream, including the world famous Colorado River.

On our ride back after our day of fishing, Churchwell doubled down on this point, directly relating it to the nearby Animas River.

Known as one of the last free flowing rivers in Colorado, the Animas River drains into the San Juan River before dumping into the Colorado River.

While the lower portion (below where Hermosa Creek enters) is a prolific stretch for anglers — including a Gold Medal fishery within Durango city limits — a large portion of the upper Animas is heavily impacted by historic acid mine drainage and struggles to support trout. It is only after clean tributary creeks enter the Animas on its course from Silverton that the toxic metals of the mining past are sufficiently diluted and no longer pose a problem to a healthy trout fishery in the lower watershed.

“A protected, clean Hermosa Creek is essential to the health of the Animas River trout fishery,” Churchwell explained. “If you’ve never heard the saying, ‘dilution is the solution to pollution.”

The successful protection legislation ensures the perfectly clean waters of Hermosa Creek will continue help dilute the metals in the Animas from upstream of the Hermosa confluence and downstream through Durango.

“This ski resort, you know why it’s called Purgatory?” Churchwell asked as we drove past ski slopes on our way out of the Hermosa Basin.

Of course, I didn’t know why it was called Purgatory.

“It relates to the original name of the Animas. ‘El Rio de las Animas Perdidas’ meaning ‘the River of Lost Souls’ as Spanish explorers first named it in 1765,” he explained. “The ski resort is themed: ski runs, lodges, etc., to reflect Dante Alighieri’s 14th-century Dantes’s Inferno.”

Finally. Something I was at least loosely familiar with.

As we descended the now protected Hermosa Creek drainage, swaths of mountain bikers, ATV users and hikers flew by us and I found myself contemplating the incredible irony of the theme of Hermosa Creek’s “partner” ski resort.

Colorado, where I had imagined things being long since uncovered and discovered, swarmed with anglers, was in fact alive and evolving. In my pursuit of Colorado River cutthroat trout, I had been challenged both physically and mentally. With the conservation of an entire drainage — the first of its kind, Churchwell and the team possibly saved the future for one particular lineage and certainly enabled the longevity of one of the West’s iconic species. They did so proudly and in a way where all were made whole.

Exploring one last feature at the confluence of the East Fork of Hermosa Creek and the mainstem, I asked Churchwell what he thinks people can take away from his experience, some would call it his legacy, at Hermosa Creek.

“Collaboration and compromise,” he said, again. “That’s all there is. That’s how it was supposed to be from the start, right?”

If Durango is, in fact, the center of the universe as Churchwell mentioned upon our first meaning, its spirit seems to be very much alive; it felt a lot more like heaven than hell.