We were just at the point of beginning to wash our hands all the time, after the first few cases were confirmed in New Mexico during my son’s spring break.

The plan was to head to Utah and fish the San Juan on the way home. We camped the first three nights at Canyonlands, where we took a couple long hikes and relaxed within unfathomably beautiful sandstone formations while Gus and the children of our friends kept to a parallel path of being teenagers. Unless we demanded their presence they were loathe to provide it, yet it was somehow fun watching my son being so intentional about staying away from his parents. Actually, everything on that trip was fun, or felt good, or at least better. Better than being somewhere else, like a city or the hospital.

Though I’ve felt safest outdoors for my entire life, the cracks began to show as the week progressed. I called the lodge and learned that the San Juan would be closing. On a supply run in Moab, we saw the empty shelves we’d heard so much about on the news. In a narrow slot canyon, we hiked within two feet of strangers, touching the surfaces they’d touched, then headed back to camp to watch the boys playfully endangering themselves atop boulders and cliffs. It became almost constant to me, that Alaska feeling that being safer outdoors doesn’t make you safe. We decided to stop running and come home.

I asked my mother — on lockdown now due to her 84 years and impaired lungs — to compare our current experience to the fears and privations she faced during World War II. Back then she was too young to even register Hitler or, more important, the meaning of him or of leaders like Roosevelt, Churchill, Eisenhower, MacArthur, and Truman. She imagines that it mustn’t have been much fun for her grandparents, parents, aunts and uncles, though given her grandfather’s success as the owner of a jam and jelly company, she acknowledged that they were probably sheltered from the worst.

Not everyone had her family’s luxury of escaping the Chicago heat and heading to Lac du Flambeau, Wisc., for the summer. Even so, her grandfather viewed reducing stress upon the greater system as a patriotic duty. He saw natural harvest as an extension of the nation’s food supplies; there were berries to be picked, stringers of bass, perch and walleye to be delivered by the men.

His was a world that had yet to invent social media, the reality TV star, and a 24-hour news stream on a perpetual quest for new ways to scare the crap out of us.

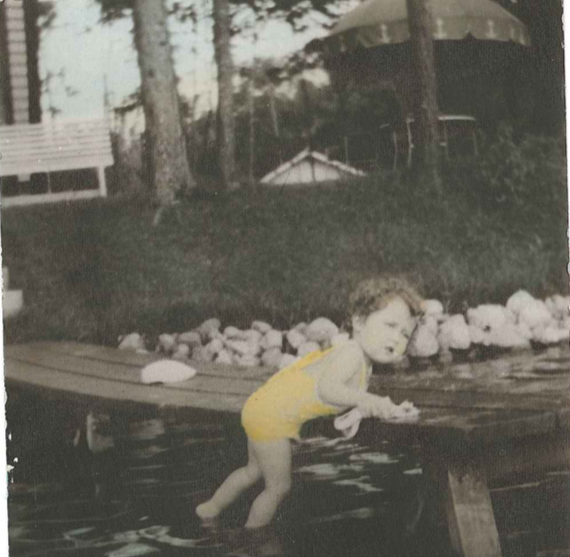

In the charge of her cousin Frank, Mom and the other kids had their own work to do. Braving mosquitoes, poison ivy and snapping turtles, they waded through lakeside bogs for sunfish and bullfrogs. Mom somehow recalls severe cooking oil shortages and says that those Flambeau summers, when they ate nothing but fish and frog legs, are why she never cooked the trout I brought home.

Among the terms we’ve embraced during this crisis, “non-essential” seems the easiest to define and the most difficult as well. I realized this last week when I got out to the property of a family with whom I’ve spent the last three years trying to lease some water to leave in the stream. It’s not a lot of water, but the lease builds on recent precedent in New Mexico, where instream transactions could be a future hedge against the impacts of climate change on trout habitat.

Our partners want to be part of creating a new tool in water management. At the same time they must find ways of monetizing their land so as not to lose it to possible development. Their property is tucked away in a scrub oak-sloped canyon that spills out onto the Great Plains. It’s a pretty place and has good (though private) fishing for wild brown trout.

Yet as I walked with one of the family members and discussed our lease, I found it difficult to justify our collaboration, its conservation value, and especially my actual career in trout advocacy as essential in a world under attack from a microscopic monster. On good days, I entertain my own hoax theory, wherein the virus has been concocted only to steer us towards our best behavior. On bad days, I’m convinced that the whole point is to numb us to the pain we cause ourselves when we’re cruel. In either scenario, talk of trout feels indulgent.

Remembering my mother’s stories, however, I suspect I might know what her grandfather might say about all this. His was a world that had yet to invent social media, the reality TV star, and a 24-hour news stream on a perpetual quest for new ways to scare the crap out of us. Her grandfather knew all he needed to know about global events and did the best he could with the things he could control.

Wisconsin sun and a lake. Oars cutting the water, bobbers going down, perhaps cigarette smoke swirling around the brim of a fedora. I hear loons after dark, and children, lots of laughing children. I see responsibility and good will put to daily practice on the smallest of scales. Because taking care of the big things required taking care of the little things.

Of course the trout matter, I think he might say, and the plants, the insects, and the spaces through which clean rivers flow. They matter now, especially now.

Toner Mitchell is TU’s water and habitat coordinator in New Mexico. He lives and works in Santa Fe.