Some years back, I got a gift package in the mail right around Christmas time. It was from my uncle John, my mom’s brother. Long and slender, the package was a complete mystery to me–we’d long since stopped receiving gift packages from aunts and uncles, so I was really curious.

Come Christmas morning, I watched as the kids opened their gifts, purposely saving the mystery box for last, and thinking long and hard about what it could be. By the time I opened the gift, I was pretty sure I knew what it was, and my suspicions were confirmed when I pulled the long aluminum tube from the confines of the box.

Scrawled on a Christmas card, my uncle had written, “Grandad would have wanted you to have this.”

With tears welling up in my eyes, I carefully unscrewed the cap to the tube and pulled out a ragged rod sock containing my late grandfather’s old bamboo fly rod. As I wept, I removed the bamboo pieces — all three of them (a butt section and two tip sections) — from the sock and soaked in the rich, caramel color of the antique. The reel seat was cracked and broken, and one of the tip sections was about six inches short — at some point, the old man had broken it, and he was using its once-identical twin by the time the rod finally became unfishable. Over time the rod also developed some “casting sets,” or long curves in the bamboo that often happen when the rod is left intact and not stored in its pieces.

I wasn’t the least bit disappointed that the rod was in disrepair — it was old and tired, but it wasn’t dead. I knew, with some money and the right restoration work, it could come back off of life support. Could I fish it one day? I figured it was a longshot. But it could adorn the wall behind the bar and be a constant reminder of the man who, to this day, is my hero.

I carefully replaced the rod in its sock and tube and stored it in the basement rafters, fully expecting to find some time to either learn how to do the restoration, or, more likely, find someone who knew what they were doing so I didn’t make any mistakes in the process.

Years passed. The kids grew up. We endured a divorce. Every couple of years, I’d pull the rod down and take a critical look at it. The cork, original to the rod, was dark with my grandfather’s sweat and the dirt and grime and fish slime that came with chasing trout in off-the-beaten path locales. For years, we’d fished the springs creeks of eastern Colorado for sunfish and the occasional planter trout. Those spring creeks have since run dry, a victim of agricultural thirst. Sometimes we’d hit the mountains and cast over beaver ponds or hike into the high country and explore. The little creeks and hidden brooks still flow today.

He’d carry the old bamboo rod and I and my brothers and cousins would be armed with a mishmash of spinning and fly rods, creels strung over our shoulders and each equipped with a can of worms or, if we were lucky, an old milk carton stuffed with freshly caught grasshoppers.

Much like the old fly rod, my Grandad was a mystery to his grandkids for a long time. In fact, it wasn’t until he died that we learned more about his past than we ever had before. It wasn’t that we didn’t want to know — he just didn’t talk about it. And, given what we know today about post-traumatic stress disorder, it makes perfect sense.

These were my favorite outings. Grandad would lead the way, and his brood of grandsons — and, later, his lone granddaughter — would dutifully follow along. We plunged through spongy willow meadows, trudged along alpine trails and took lessons from the old man as he stood over our shoulders and patiently watched.

And while we fished with whatever implements he was able to assemble from his storeroom, he fished with his old bamboo classic. We all coveted it. On rare occasions, when he’d let one of us cast it, we could immediately feel the difference. It wasn’t a clunky, heavy glass rod. It was supple, but surprisingly light. It felt … superior. And, of course, it was.

I knew precious little about the rod until my uncle gifted it to me all those years ago. And while it took me years to finally dive into the restoration process (which was incredibly easy, frankly), I did pick up bits and pieces of information about the rod over time. But, only when I called a friend of mine who builds and restores bamboo fly rods did I learn of the rod’s true origins.

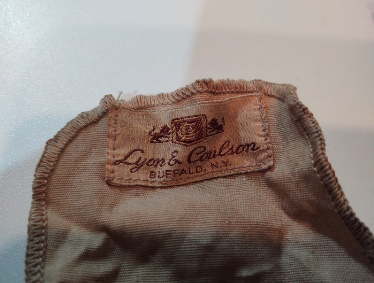

It’s a Lyons and Coulson Imperial, model #0200. It’s 7 and a half feet long, and it comes in two-pieces with the spare tip. It was manufactured by a team of builders in Buffalo, N.Y., sometime between 1935 and 1940, and was a sought-after rod because of its length and light-line casting ability. My friend did quite a bit of research, and noted that the L&C Imperial is virtually identical to the Heddon’s Black Beauty Model #17, also a desired rod at the time. These rods were generally produced in 3- and 4-weight models, but my restoration friend uncovered some information that indicated all L&C (and Heddon’s Black Beauty) models either cast a 4- or a 5-weight line.

Much like the old fly rod, my Grandad was a mystery to his grandkids for a long time. In fact, it wasn’t until he died that we learned more about his past than we ever had before. It wasn’t that we didn’t want to know — he just didn’t talk about it. And, given what we know today about post-traumatic stress disorder, it makes perfect sense.

My grandfather was a Marine who fought in some of the most brutal battles in World War II — he survived the battles of Guadalcanal, Peleliu and New Britain in the push toward Tokyo. Until the day he died, he never spoke of the horrors he most certainly endured (although he did tell us grandkids that the bald spot atop his head was a gift from a near miss fired from a Japanese cannon–and we believed him, of course).

He grew up a farmer on the plains of eastern Colorado and eventually moved his family to the Denver suburbs in the late 1950s, where he worked until he and my grandmother retired as a carpenter and handyman. He could build anything he wanted and he loved what he did. But to me, he was my hero … a mentor to me in more ways than I can count.

Was he flawed? Certainly. Anyone who returned from combat in the South Pacific after World War II very likely battled demons from then on, as I know he did. But it didn’t stop him from being a proud grandfather who made time and created opportunities for each of his eight grandkids. Whether it was sitting in the stands at baseball games or salving a host of savage mosquito bites earned while casting to wild brookies swimming in beaver ponds at dusk, he was ever-present. He was, to me, my brothers and my cousins, godly. Immortal.

So, when I sold my house and moved this last winter, one of my priorities was to finally take the plunge and have the old rod restored. I called my rod-building friend who lives in the same neighborhood, and I dropped the rod off in its original state of disrepair. He took the parts and pieces and, with a few strategic purchases and some significant time spent on the finish work, completely restored the old Lyons and Coulson Imperial. He even found a compatible second tip for the rod.

“Do I dare fish it?” I asked in an email to my friend. The last thing I wanted to do was take the rod out and then break it again.

“You can absolutely fish it,” was the reply.

So, a couple of weeks ago, I took the old rod out of its tube and sock and assembled it streamside on a little backcountry creek that flows into Idaho from the wilds of Yellowstone National Park. I attached a 5-weight line — the same set-up I use for a 5-weight Sage LL Trout rod that I’m lucky enough to own — and I went fishing.

As I gripped the cork, dark with years of Grandad’s sweat and fish slime, I remembered those early casting lessons with that very stretch of bamboo. I remembered the hand on my shoulder and the gentle coaching. I made a couple of tentative casts and I smiled as the line slid perfectly through the guides. And when I brought that first diminutive brook trout to hand — and that was a fitting fish for the rod’s rebirth, because I imagine, over the years, we caught hundreds of brookies together — I remembered the slap on the back and big grin across the face of my grandfather.

I lost Grandad in 2006. I last fished with him in 2003. But I have the old fly rod, rebuilt and rejuvenated. And I have the memories it contains … the lessons it taught.

I have the history … the origins of my own journey he was kind enough to help me start. I cried a little as I cast, and I’m sure the smile was there, too. It was bitter, but oh, so sweet, to ply a trout stream with the old man again … to fish without a care.

I miss him. Every day. But, through that old fly rod, he visits now and then. And for that, I’m so very grateful.