TU promises legal action if the Potter Valley Project continues to harm salmon and steelhead

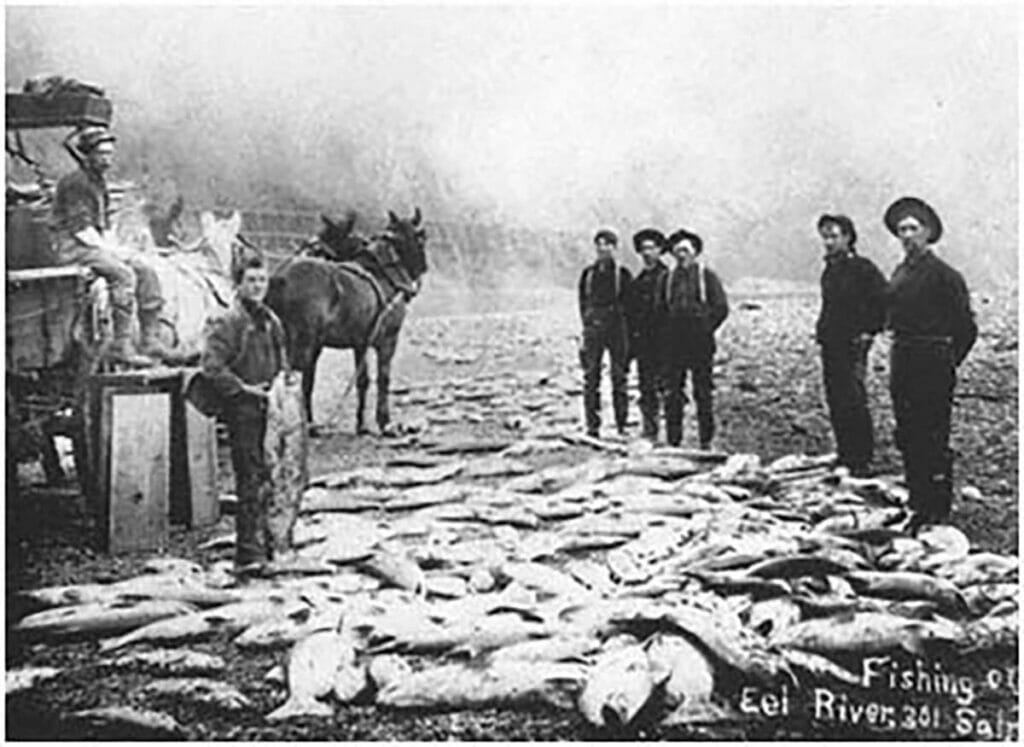

The lower reaches of California’s Eel River flows through the homeland of the Wiyot people. The Wiyot call the river Wiya’t, which means abundance. At one time, the Eel’s salmon, steelhead, and Pacific lamprey fisheries were incredibly abundant.

But dams, major water diversions, legacy impacts from clearcut logging, and illegal cannabis cultivation have compromised the Eel’s productivity for salmonids and lamprey.

As many as 800,000 Chinook salmon used to return to the Eel every year. Now, perhaps 3,000 do in a good year. And while the Eel remains one of the best places to fish for wild steelhead in California, much of the highest quality habitat for anadromous fish is blocked by two obsolete dams.

Now, though, the prospects for recovery of Eel River salmon and steelhead are better than ever. But these prospects may hinge on an action to which Trout Unlimited almost never resorts: litigation.

This month, TU joined four of our conservation partners in California in filing a notice of intent to sue Pacific Gas & Electric if it does not take immediate action to end the harm its dams are causing the Eel’s threatened salmon and steelhead. Our ultimate goal is removal of the two dams, which studies have shown to be the best way to recover of Eel River fish populations.

The Eel got its contemporary name from a white settler who, the story goes, traded a frying pan to Wiyot fishermen in 1850 for some of their Pacific lamprey—which are not actually eels but rather prehistoric jawless fishes that like salmon and steelhead are anadromous — were once an important food source for the Wiyot and other native peoples. But it is the Eel’s salmon and steelhead runs that made the river famous among modern fisherfolk.

Despite a century of land uses that have depressed salmon, steelhead and lamprey runs in the Eel, there is now real hope that its fisheries can be restored. That’s because the Eel still offers significant amounts of high quality habitat for salmonids—more than 200 miles of it, in fact, on public lands upstream of the Scott and Cape Horn dams.

And thanks to more than 20 years of TU-led restoration work in Eel tributaries, which has reconnected and improved habitat quality and function in dozens of miles of stream throughout the basin, California’s third largest river system is primed for a dramatic rebound of its salmon, steelhead, and Pacific lamprey populations if the dams are removed.

“The Eel offers one of the best opportunities for wild salmon recovery in California, thanks to intact habitat above the dams and the improvements in habitat quality and connectivity TU and our restoration partners have done throughout the watershed,” said Charlie Schneider, former president of TU’s Redwood Empire Chapter and now coordinator of the Salmon and Steelhead Coalition.

That’s why TU has been a leader in negotiations and licensing proceedings to upgrade or remove the two hydropower dams and diversion infrastructure that comprise the Potter Valley Project (PVP), he said.

PG&E owns the Potter Valley Project, which never has actually generated much hydropower. In recent decades rising operational and maintenance costs and competition from other energy sources made it a money-losing project—so much so that PG&E no longer wants to own and operate it.

Even if PG&E wanted to keep operating the PVP, as of April 14, it couldn’t do so legally. The federal license to run the project officially expired on that date. But the dams still block salmon and steelhead migration, and PG&E still owns them.

Under the operating license, PG&E was granted permission for “take” (i.e., harm, harassment or killing) of a number of species protected by the Endangered Species Act, including salmon and steelhead. Now, PG&E no longer has that permission, yet the utility has not explained how it will ensure the defunct project does not violate the ESA.

Moreover, the National Marine Fisheries Service has concluded that restrictions imposed by federal fisheries biologists under the permit were inadequate, and that the project is harming fish in ways the agency never would have.

Given the precarious state of California’s native salmon and steelhead, and the high potential for their recovery in the Eel, the status quo won’t cut it. PG&E must act immediately to eliminate the project’s take of these fish.

To ensure that PG&E delivers this legally mandated outcome, TU joined with Friends of the Eel River, the Institute for Fisheries Resources, the Pacific Coast Federation of Fishermen’s Associations, and California Trout to file a legal notice with PG&E arguing that the Potter Valley Project continues to cause harm to Chinook salmon and steelhead populations, and that to the extent PG&E had federal permits to harm listed species, that coverage terminated on April 14.

The notice states that these parties will sue if PG&E does not act within 60 days to cease the take of listed species. Schneider said the step is simply a way to ensure that PG&E upholds its legal obligations.

“Litigation is really the option of last resort for Trout Unlimited,” Schneider said. “Almost all of TU’s conservation achievements are realized through collaborative efforts, often with businesses interests such as water providers, ranchers and timber producers. But when the stakes are this high, and cooperative measures have proven insufficient, TU will do what it takes to protect and restore wild salmon and steelhead and fisheries such as the Eel, which is primed for return to its former glory.

“In some ways the river is in much better shape than it was a few decades back,” he added, “and it is gradually becoming a destination steelhead fishery again. But we have to keep moving toward recovery. PG&E’s two dams remain the single biggest problem for Eel River steelhead and salmon, and until the dams are removed, PG&E must do more to reduce their impacts on fish and fisheries than simply continue business as usual.”

Learn more about TU’s work with the Salmon and Steelhead Coalition partnership to restore the Eel River.