Our public lands are the foundation of healthy watersheds and strong communities. From remote trout streams to working forests and rangelands, these places provide clean water, vital trout habitat and public access for all Americans. But pressures like efforts to sell off and privatize public land threaten what makes them so valuable.

This blog series highlights the people and places at the heart of these landscapes—and the practical, local perspectives keeping them accessible, productive and resilient for generations to come.

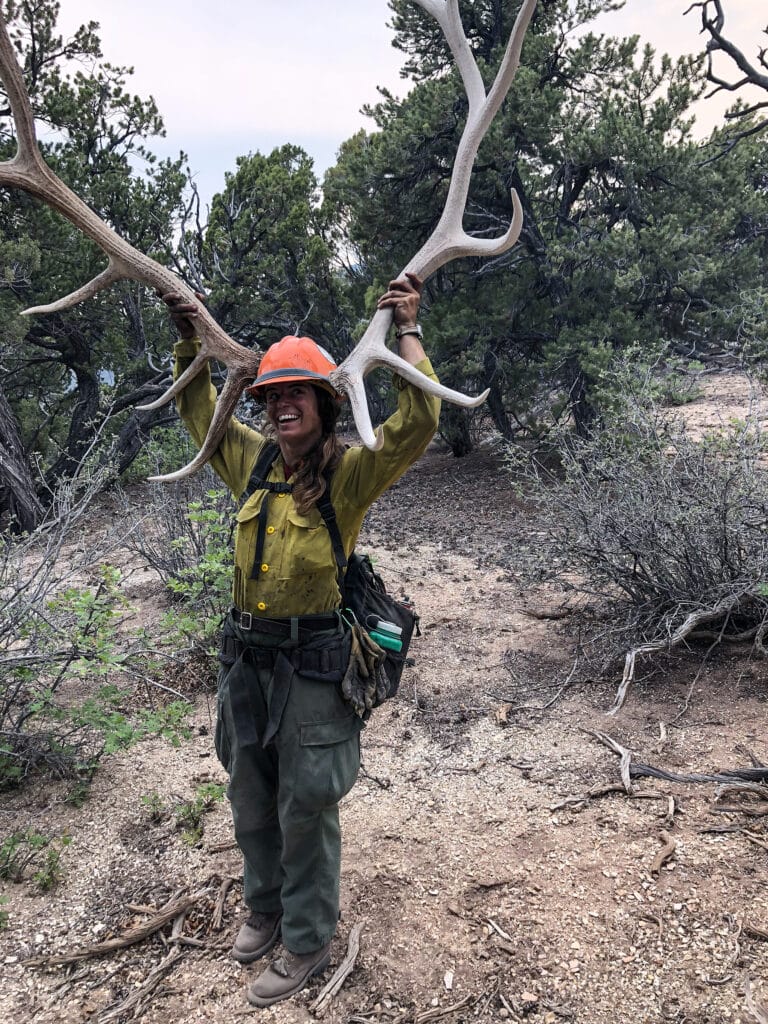

Long before she moved west to join a wildfire fighting crew, Amanda Monthei grew up fishing, hiking, hunting and camping in Northern Michigan’s Pigeon River Country, a vast network of state public lands surrounding her rural hometown.

Warmwater species—bass, panfish and walleyes—were the fish of choice in the local lakes and streams. She started fishing as soon as she was old enough to hold a rod, and even before she was comfortable handling fish on her own. She laughs telling a story of being a young child, fishing from a dock while her father tried to clean the family’s boat, but she kept interrupting him to unhook the bass she was catching one after another.

Fly fishing, and trout and steelhead, came later. After initially being frustrated by the steep learning curve of knots and casting, it soon became one of her favorite ways to explore the landscape and interact with the water, fish and bugs that make up watershed ecosystems.

The question of where and when to fish, or what was around the next stream bend, was never far from her mind. “When looking for new fire crews to apply to, I’d make sure they had good access to fishing and public land access keep myself busy on days off,” she explains.

A storyteller and educator

Nearly as long as she’s been fishing, Monthei has been a writer. Trout Unlimited members might recognize her byline from stories in TROUT, Wild Steelheaders United, The Flyfish Journal, Outside, The Drake and Field and Stream, or her recent story “Leave it to Beavers” for Patagonia.

For “Leave it to Beavers,” Monthei joined TU’s Northeast Oregon Hand Crew Initiative for a work stint on Cable Creek, a headwaters tributary of the John Day River basin, to document the habitat restoration work being led by partners at Trout Unlimited, the NW Youth Corp, the U.S. Forest Service, and others.

Her story weaves together ecological lessons with the experiences of the young adults spending their summer learning stewardship and building beaver dam analogs (BDAs) alongside TU staff. It includes vivid descriptions of water returning to connected floodplains, expanding habitat for endangered salmon and steelhead, and stretches of the stream where beavers took over the crew’s work from the summer before, flooding a low-lying valley bottom through a stand of fire-scarred trees.

The inclusion of the burned trees interacting with the restored wetland isn’t an accident. It is exactly the type of detail she wouldn’t miss.

Life with fire

When she’s writing about fishing or skiing, Monthei tells a great yarn; but the experience of fighting wildfire, and fire’s ecological role in the western landscape, has been a focus of her work for nearly a decade.

A few years after graduating from college, Monthei moved west to work as a wildland firefighter. She spent four seasons on the ground, including two years as a part of a busy hotshot crew. Most of the work took place on federal public lands across the west, but occasionally the crews worked on state lands or in places where they were defending private homes or structures. Much of the work involved digging hot lines and burning vegetation to reduce fuel loads ahead of advancing fires. It was demanding, high-stakes work, but it was also profoundly eye-opening.

“I realized I didn’t really know anything about fire,” Monthei explains. “I’d watch flames rip across entire hillsides in seconds, and it made me want to know more about the science behind fire and forest management. I didn’t understand the ecology nor how practices like logging and fire suppression have impacted the landscape. I realized there were lots of people like me, and that we should all know more about this.”

While continuing to write as a freelancer, Monthei eventually shifted from working directly on wildland firefighting crews to supporting firefighting and wildfire awareness in various communication roles.

She also launched her podcast “Life with Fire.”

The podcast is a forum to discuss the nuances around wildfire through conversations with experts, stakeholders and the people who fight and manage the fires themselves. “I wanted to keep learning, and the podcast was a way to talk to the smartest people I can find in the wildfire space,” Monthei explains.

“Western landscapes evolved with fire,” she continues. “It is a topic that is susceptible to extreme views, and I want to help explore it in ways that digs into the science and gives space for complexity.

“Not all fire is bad, and it can often be necessary and positive in the long term for the landscapes and watersheds we all love. But fires are also growing more costly and more destructive, and seasons are lasting longer. My hope is to increase the cultural fluency around wildfire and these nuances, so we can more quickly find solutions to help us coexist with wildfire, and its impacts, into the future.”

Through her work, Monthei has created an important space to grapple with the implications of wildfire for landscapes, ecosystems and people. She’s become an important resource to the public, and as a result has had opportunities to think aloud about fire on National Public Radio, in The Atlantic and The Washington Post, and numerous other newspapers, podcasts and magazines.

Care and celebration of America’s public lands

Our shared public lands have been a constant throughout Amanda Monthei’s life, work and advocacy. Whether she’s fishing, skiing, mountain biking or hiking, they have provided places to explore, recharge and spend time with friends and family.

These incredible landscapes also offer lessons and inform the stories she tells as a writer and science communicator.

Through the experience of wildfire or her curiosity to better understand how ecosystems function, these places offer constant reminders of their dynamism and affinity for change.

Disturbances are a natural, and required, part of how ecosystems work and sustain themselves. It is up to all of us that depend on these landscapes to help build better ways to protect and restore them. And have the conversations that drive that process.