In June 2013, researcher and fisheries biologist Ashley Rust and her family were at their family cabin near Creede, Colo., when an afternoon rainstorm—a frequent occurrence in the San Juans at that time of year—worked through the area.

The system brought little in the way of rain but contained lightning all the same, andover the next few days, Rust watched as multiple smoke plumes began rising from the nearby mountains.

“At first, people are used to living in the wild and it’s like ‘okay there’s a fire; it’s not too big of a deal,’” Rust said. “But as plumes started to grow, we could feel the anxiety building intown—the chatter was increasing, there was intensified communication among neighbors, people were meeting in town and talking about what’s going on and preparing to mobilize.”

Three plumes popped up over the next week, all within eyesight of Rust’s cabin. The three fires combined to form the West Fork Complex, a series of fires burning in such close proximity to each other that they were managed as if they were one large fire. The complex ultimately burned almost 110,000 acres in the San Juans, near the headwaters of the Rio Grande—a place that Rust and her family hold dear. Rust had never really had a personal involvement with fire like this, but it was this experience of watching a fire burn close to her community—and through the mountains and rivers that she loved—that ultimately sparked a new trajectory for her research and career.

There’s a “chicken or the egg” scenario in fisheries biology, one where most fisheries biologists were either anglers before getting into the field or became one soon after, or maybe don’t even remember which came first—the lines blurred by countless long days in waders. But angling is an inevitable interest when your career revolves around a fascination for fish and an affinity for walking around in rivers.

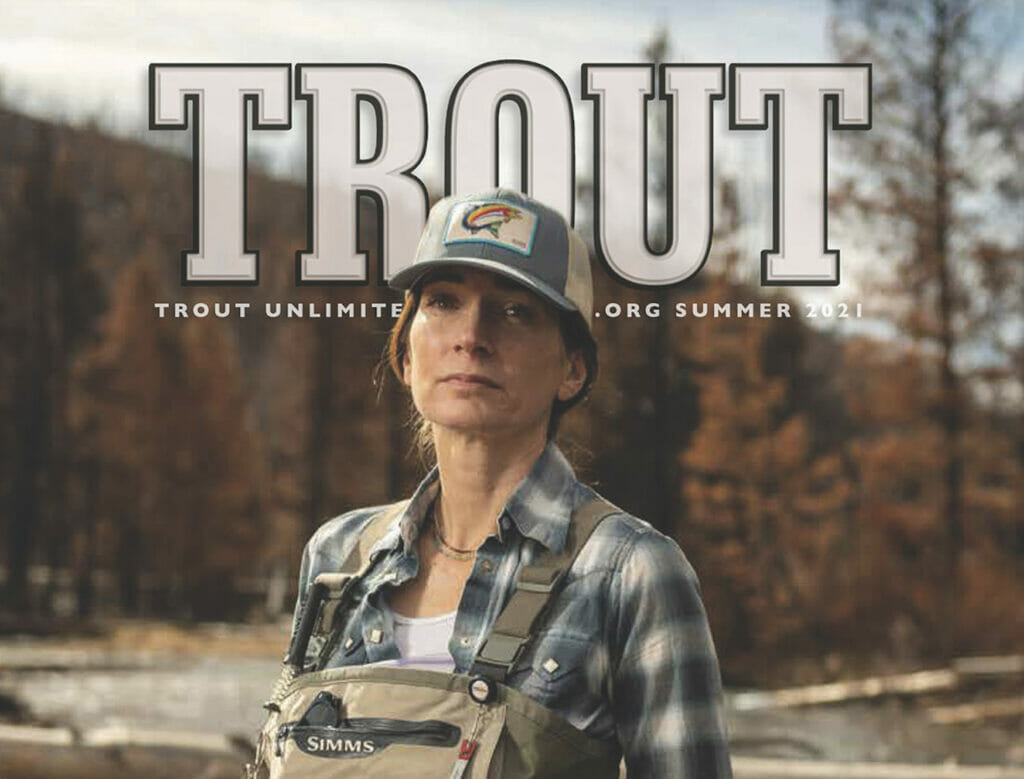

Rust, a research associate at the Colorado School of Mines, falls into the former category; she spent her childhood fishing in Colorado before pursuing the biology route in college. “In my case, I was an angler first and loved being outside and in the river, so this career appealed to me,” she said. “I do love to fly fish and I bring my rods with me whenever I go out in the field to do work, hoping to squeeze in an hour. It certainly makes me care more about the stream’s health, as I get to interact with fish, catching and holding them—and I want their home to be healthy and their future to be bright. It also helps me share my science if I am able to talk to anglers about the river and how a fire may impact their favorite spot.”

There’s a “chicken or the egg” scenario in fisheries biology, one where most fisheries biologists were either anglers before getting into the field or became one soon after, or maybe don’t even remember which came first—the lines blurred by countless long days in waders. But angling is an inevitable interest when your career revolves around a fascination for fish and an affinity for walking around in rivers.

Rust can trace the origin of her interest in fisheries to her own “favorite spot” from when she was a kid: one summer, her family’s favorite fishing spot became overrun by invasive species, effectively turning a trout fishery into a pike fishery. She was fascinated by the change and what had caused it—and how she could prevent similar things from happening to other systems.

“That was a first-hand experience; this was an environmental problem and I wanted to be a part of solving it,” she said. Rust eventually ended up at the University of Michigan, where fisheries “was not as weird of a field to be in,” as it was in the Rocky Mountains at that time. And just as how invasive species impacting her homewaters piqued her initial interest in fisheries, Rust’s eventual career and research ended up hinging heavily on similar water quality impacts in her backyard as an adult.

By 2013—with a master’s degree, three sons and a teaching gig at Metro State University of Denver—Rust Recognized that there was a considerable amount of work already being done in water quality and fisheries in her area. She knew she needed a PhD to do the research she was interested in, and after enrolling in the School of Mines in Golden, Colo.,set about finding a focus for her doctoral dissertation. It wasn’t until the West Fork Complex burned through the lands adjacent to her cabin and the headwaters of the Rio Grande River, that she realized she’d found her focus.

“Watching (fire) from a community perspective really impacts you—there’s a panic and devastation you feel around watching that kind of catastrophe,” she added. “But It actually wasn’t until a good friend and colleague of mine called me in the middle (the fire) and said, ‘Hey aren’t you looking for a project? Why don’t you use that as your project?’

“It hadn’t occurred to me to connect the dots.”

After attending a few community meetings that were held by the fire’s management team, Rust decided to study the long-term impacts of wildfires like the West Fork on water quality,fish and aquatic ecosystems in the San Juans, a focusthathasframedher research since she completed her PhD in 2017.

“Somebody literally asked in one of the meetings, ‘We have all this money and bought all this water quality equipment, but we don’t have the labor or expertise to use it and monitor what’s going to happen to these rivers after fire.’ And I just happened to be in the room looking for a dissertation project and just kind of raised my hand,” Rust said. “Lots of things came together in a beautiful synergistic way.”

One essential truth of Rust’s subsequent dissertation and research career has been that fire is an essential ingredient for healthy forests, healthy rivers and healthy fish. But there’s always nuance and recognizing and researching that nuance has grown ever more important as climate change and forest mismanagement—and a slew of other issues—continue to drive an alarming increase in the size and intensity of wildfires in the West.

Fires have been a part of earth’s landscapes for over 400 million years, and the landscapes of the West have evolved right alongside a regular presence of fire. Indigenous tribes long coexisted with fire, as well—namely, by regularly igniting their tribal lands for cultural or ecological purposes, whether to encourage the growth of medical or edible plants or to make the landscape easier to navigate for hunting and other activities. These burns were extinguished and criminalized as Europeans colonized the West and built homes, infrastructure and railroads that would be threatened by wildfires.

Over a hundred years of fire suppression later, and we have forests that are overgrown, deeply affected by bug-kill and drought and thus growing more flammable by the year—particularly as climate change contributes to drier fuels and more extreme weather patterns.

But just as the landscape has coexisted with fire for millennia,so too have the fish. Native fish species, in fact, are uniquely adapted to the types of disturbances broughton by fire—whether that’s a short-term change in water temperature, a surge of nutrients and sediment or seemingly devastating erosion events that occur during and after wildfires.

“They’ve adapted with fire—some fish may die in [fires] but most don’t,” Rust said. “Fires help rejuvenate the stream, and literally just like the pine trees and the fireweed and the plants that have evolved with fire, so have the fish in all of these Rocky Mountain systems. They’re used to all these disturbance events, whether it be fires or floods or landslides—these are all types of disruptions that are a part of their landscape.”

Introducing modern, man-made problems into the fire equation changes things, of course. Fire suppression tops the list of modern problems brought about by humans, but there’s also the growing impact of climate change and the increasing propensity for people to build homes in fire-prone landscapes. In the fisheries realm, there’s the introduction of dams, culverts and other impediments that make fish movement in the aftermath of destructive wildfires nearly impossible, contributing to greater fish kill.

And, in the San Juans of Colorado, there’s one very specific way that human activity has worsened wildfire impacts on water quality and aquatic ecosystems: mining. Many of the historic mines in the San Juans have been lying unused since their heydays in the 19th and 20th centuries. But when fires burn over these old mines, brush and mature trees that would normally prevent erosion are sometimes burned so severely that they no longer stabilize the soil. This exposes toxic mine tailings to the elements after having been covered by vegetation for decades—often resulting in toxic runoff during rain events in the aftermath of large fires.

Exploring how those heavy metals impact the algae, insects, fish and humans downstream is the part of the fire and fish interaction that Rust has taken a deep interest in since earning her doctorate. Heavy metals, she explains, don’t just find their ways into streams in areas with heavy mining history, but are also present in areas with naturally mineral-rich soil—and tracking how both types of runoff might impact downstream ecosystems and users will be critically important as large fires continue to affect watersheds in Colorado and beyond.

Right now, Rust is looking at how the 416 Fire—which burned 57,000 acres in the San Juans in 2018—moved metals into the Animas River and how those metals are being “taken up” by insects as well as what that might mean for the food chain and downstream water users.

“What we’ve seen is that the insects take up the metals in the water column, the metals are observed and in the insect tissue but not in the algae.”

This, of course, has serious downstream implications. Not only are these heavy metals present in the water column, but they will also inevitably impact fish populations that eat insects in the affected areas, which ultimately makes its way to humans. But this is just one unique issue in one specific region. Fires, on the other hand, will continue to impact watersheds all over the country (and continent…and world) in ways that are both anticipated and—as climate change’s influence grows and fire intensities build—unprecedented.

An essential element of Rust’s research is tracking and recognizing the impacts of upstream disturbances on downstream populations. Rust works with Dr. Terri Hogue, an expert in post-fire hydrology with a shared enthusiasm for field work in streams at Colorado School of Mines. While there are countless ways upstream disturbances can be problematic (particularly with mining), there are also a myriad of benefits that come from the effects of wildfires on watersheds and fish—and allowing these systems to respond naturally to natural events will help maintain that system’s resilience to future disturbances like fire.

“In the long term, it’s good to recognize that [fire is] part of the landscape, that we’ve all evolved with it, and at some point it won’t be such a scary looking burnt-out landscape,” Rust said. “So far I’m seeing that the insects and fish actually bounce back faster than the vegetation or the land does. So, you look around a burnt landscape that might look devoid of life, but the water might be just fine.” Humans have a tendency to want to intervene in the recovery of watersheds that have been burnt over, which is understandable and helpful in some cases, but Rust insists that sometimes the best thing we can do is be proactive and ensure those systems are resilient before they’re impacted by a fire.

“The best thing we can do is keep our waters connected [by getting rid of unnecessary dams, diversions and other impediments],” she said. “There’s no mitigation that needs to happen after [fires]—we don’t need to restock or be more aggressive on that. We need to acknowledge that we need to clear fish passages, give it time, and recognize that some spots are going to be muddy for a couple years after the fire when it rains.”

Getting rid of unnecessary blockages in systems—that is, dams or diversions—will help ensure that fish have a place to go during large disturbance events, which is an instinct that has been finely honed over millennia as these fish have adapted and survived in these environments. And while Rust mentions that heavily managing fisheries following a fire event isn’t always necessary or even beneficial, other human interventions could be useful in the attempt to build better forest and river resiliency.

“We [should] allow more fire and get used to tolerating it—and that means addressing the folks that build in the woods and encouraging different zoning or fireproofing their house, so that firefighting efforts could be reduced and we could tolerate more fire on the landscape,” Rust said. “We also [need to remember ]that our fish are going to be okay as long as they have connected waters.”