Our public lands are the foundation of healthy watersheds and strong communities. From remote trout streams to working forests and rangelands, these places provide clean water, vital trout habitat and public access for all Americans. But pressures like efforts to sell off and privatize public land threaten what makes them so valuable.

This blog series highlights the people and places at the heart of these landscapes—and the practical, local perspectives keeping them accessible, productive and resilient for generations to come.

Jason Barr, born and raised in the shadow of Mt. Shasta at the tail end of the Cascade Range in northern California, has, you might say, an appetite for risk.

Hucking huge air while skiing near vertical backcountry chutes in winter, check. Hucking huge air on downhill runs on a mountain bike as he nears the half-century mark in age, check. Wading chest-deep in the tricky footing and frigid swirls of his favorite water, Oregon’s North Umpqua River, to raise a steelhead, check.

Some adrenaline junkies are Clark Kent at work. Not Jason. His office is uninsurable for risk, and he has the furthest thing from a desk job. For the past 25 years, Jason Barr has been a wildland firefighter. That’s right. He has one of the most dangerous jobs there is.

Life fighting wildfires

Leaving aside the truly terrifying conditions encountered on a wildland fire, there are other perils of the profession. When we spoke for this story, he was, in his words, “covered in poison oak.” Jason is a fire captain with CalFire, the California agency dedicated to preventing and fighting wildfire. He runs an inmate crew, which had recently been responding to blazes ignited by some 6,000 lightning strikes in the region.

Jason, “just doing his job,” felt compelled to scout one fire by plowing through dense 20-foot-high stands of undergrowth, mostly poison oak. The heavy, specialized clothing wildland firefighters wear on fire apparently doesn’t prevent the vicious oil exuded by Toxicodendron diversilobum from contacting one’s skin.

Yet Jason didn’t seem to be feeling too sorry for himself. “The thing is,” he says, “I was looking down on the Salmon River, one of my favorite places on earth, and I was helping to protect it from being nuked by sediment after winter precipitation next year.”

You do not want Jason’s job. You do want a seat in Jason’s boat when he takes to the water to fish, because, he says modestly, he is “pretty productive.”

Adventuring on public lands

As a child, Jason was always outdoors. His parents were active folks—his mother worked for a whitewater rafting outfit, and their property bordered national forest land. They spent more time in the timber, streams, meadows and slopes of their scenic backyard than in their house.

Jason was, he says, “adventurous.” One time when he was two years old, he simply wandered off into the woods. His mom, he says, “got a little worried, but I eventually found my way back.”

He also found his way to adventure sports; ski racing, dirt biking, mountain biking, whitewater kayaking—anything that redlined his pulse.

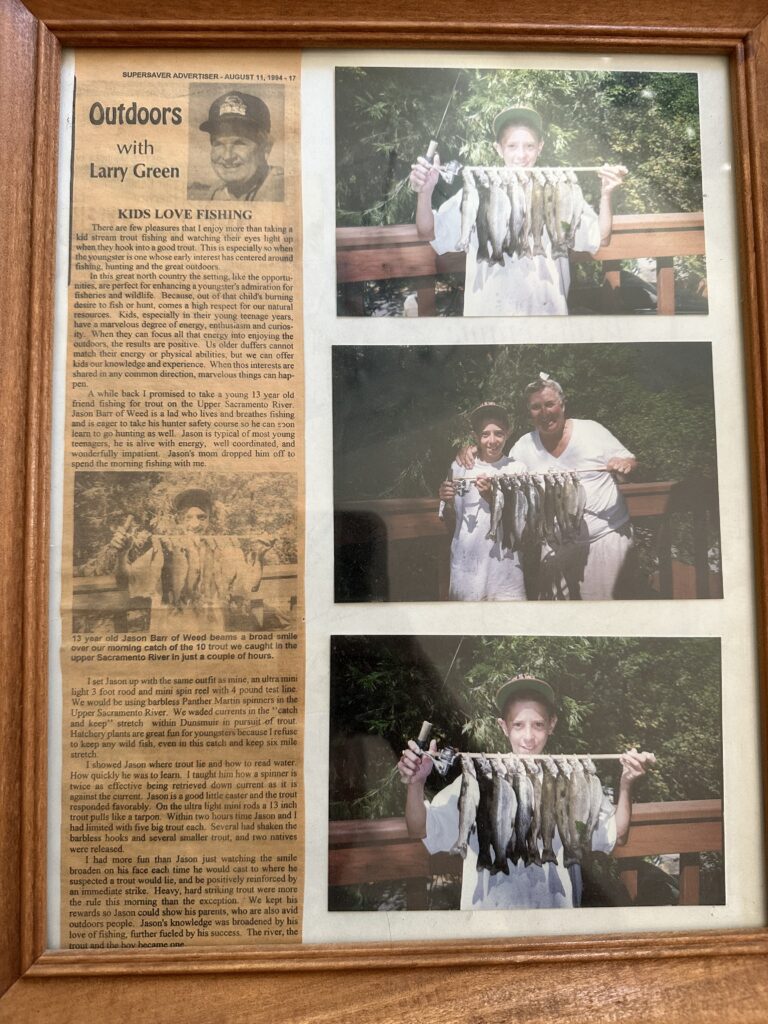

He learned to fish early on, too, plying the McCloud and Upper Sacramento Rivers with spin gear for tough wild trout, thanks in no small measure to a local man named Larry Green.

Green was an avid fisherman and wrote columns for Western Outdoor News and the San Francisco Chronicle. He gave Jason his first job, stacking firewood. He also taught Jason how to cast and gave him his old fishing gear to get him going.

About that time, some of the private lands around the Barr residence were being sold off and subdivided. A favorite trout stream got posted No Trespassing. It was one of the most influential experiences of his life.

“We are very fortunate here to still have so much wild, rugged land around us, and to have access to most of it for outdoor recreation,” he says. Recent proposals in Congress to sell off public lands hit hard. “When you grow up in a place like this,” he says, “you understand maybe better what’s important. We just can’t have the policy of the country be we’re going to sell off or give away public lands without any local involvement.”

Many of the public lands around Jason’s home would have qualified for disposal under the language recently considered by Congress as part of the budget reconciliation bill process.

Protecting the places you live and love

In July 1991, a train derailed and dumped 19,000 gallons of herbicide into the upper Sacramento River—not far downstream from Jason’s home. In 2018, the Delta Fire burned 60,000 acres of mostly national forest land in the same stretch of the “Upper Sac” as that wasted by the chemical spill. Happily, today this reach’s famously selective trout are back. But to Jason, these events were a reminder that you can’t take for granted the places you love.

That’s why he is increasingly dedicating time to conservation and advocacy for public lands. Jason is a member of the Steamboaters, a group of avid fisher-folk dedicated for the past half-century to conserving and restoring the North Umpqua’s steelhead. He’s also president of the local chapter of the International Mountain Biking Association (IMBA).

“I mostly keep to myself,” he says, “but this is a time when we need to stand up and get involved to keep what we love.”

For Jason, his job is more than a profession. It’s also directly helping to defend and conserve the lands and waters that shaped him. Extreme wildfire can render trout streams and even whole watersheds sterile for years. We have been suppressing fire for too long on the landscape, he says. We need to be more proactive, with more focus now on fuels reduction and management. “It’s very challenging right now,” he says, “because everything is so overgrown.”

So, Jason works — a lot. It’s hard, hazardous work. But there are benefits you might not imagine. “One of the things I appreciate most about my job,” he says, “is I get to see sunrises and sunsets from places where no one else will ever see them.”

The North Umpqua, lovingly cradled in public lands, is Jason’s spiritual home. A good friend took him there for the first time some years back, when Jason was recovering from a serious and scary health challenge. He landed an 8-lb steelhead that day – and has gone back at least once per year ever since.

In 2019, Jason celebrated as years of work by Trout Unlimited, the Steamboaters and other fishing and conservation interests paid off in the passage of legislation that established the Frank and Jeanne Moore Wild Steelhead Management Area, 100,000 acres of permanently protected public lands and water dedicated to conserving the North Umpqua’s legendary wild steelhead.

The week after our conversation, Jason is making the pilgrimage to the North Umpqua again, to skate flies for summer steelhead. “Getting Zen, just me and my dog,” he says. “It’s always a good reset – it’s such a beautiful, grounding place. Definitely a strong connection [for me]. We need to make sure it’s here for our kids’ kids’ kids, so they can have the same connection.”

Jason Barr and TU’s California Science Director Rene Henery have been friends for more than two decades. They are both fearless, skilled, and hard core — highly compatible partners that get together to feast from the Shasta region’s extraordinary menu of outdoor recreation opportunities. Barr says of Henery, “He is such an amazing person. I always feel so grounded when we spend time together.”