Raising a family amid a campaign to protect Alaska’s wild fish

Author’s note: My story is one of many who have invested in this fight over decades and generations. This is written with gratitude to the entire community of advocates that continue to push back this irresponsible mine. I acknowledge my privilege in choosing to do this work and recognize that the people of Bristol Bay haven’t had a choice, this is a daily fight for their way of life and culture.

Written while working on the ancestorial lands of the Dena’ina Elnena people in Anchorage and the Yup’ik and Dena’ina people of southwest Alaska.

In the fall of 2010, I gently bounced my two-month-old son on my lap, willing him to sleep peacefully as I listened to the talk at a strategy meeting on protecting Bristol Bay. A mining company that was gaining momentum, had financial backers and support. Protective measures that could help prevent the destruction of wild salmon habitat. A little-used provision of the Clean Water Act.

I felt gratitude for my colleagues and all the local people who had been fighting this proposed mine for years, happy to contribute in whatever small ways I could.

Sleep deprived as I was in that parent-of-a-newborn stage, it seemed clear in my mind that the Pebble mine proposal was a terrible idea. Why would we want to ruin a food source for millions in exchange for gold and short-term profits?

And yet, the path to stopping a mine of this magnitude seemed steep and not well marked.

We dug in, many of us juggling community outreach efforts, events and urgent conversations on fishing boats, often with young families in tow.

All the conversations with thousands of Alaskans made a difference. In time, a majority of our neighbors came to the same conclusion: Bristol Bay was no place for a giant mine.

Fast forward to the following year. I held my 10-month-old son on my hip as I testified alongside other mothers and fathers, anglers, business owners, commercial fishermen, scientists and friends—in solidarity with local people—urging the EPA to listen to the scientists projecting destruction of the fishery, and to take swift action to protect Bristol Bay’s fish, and jobs and communities.

Again, it seemed like common sense. Indigenous cultures relied on salmon for food and spiritual sustenance since time immemorial. Alaska’s economy thrived on salmon. Salmon runs were declining up and down the Pacific Coast.

Why jeopardize it?

New friends warmly welcomed me to kitchen tables and shared their best salmon chowder and three-day smoked salmon. They entertained a growing toddler, feeding him snacks of fresh foraged foods gathered from the lands and waters. They showed me, us, the magic of Bristol Bay.

The EPA continued to compile the science and gather input from Alaskans. Support for protecting Bristol Bay poured in from around the country.

In 2014, the EPA proposed that, yes indeed, Bristol Bay deserved to be protected. Celebration!

My son was three. We marked the occasion with a do-it-yourself trip to the wild rivers of Bristol Bay. He caught his first trout as we explored the bounties of the Kvichak River.

But the case was not closed. The Pebble Partnership sued the EPA on procedural grounds.

Amid the uncertainty, my husband and I had another baby, a girl. She had sparkles in her eyes as she hitched a ride in my chest pack to more meetings, hearings, events, a training program for young Bristol Bay residents. She was entertained with stickers. We cheered along-side other mothers, fathers, sons and daughters as Barack Obama, the first sitting President to visit Bristol Bay, arrived in Dillingham.

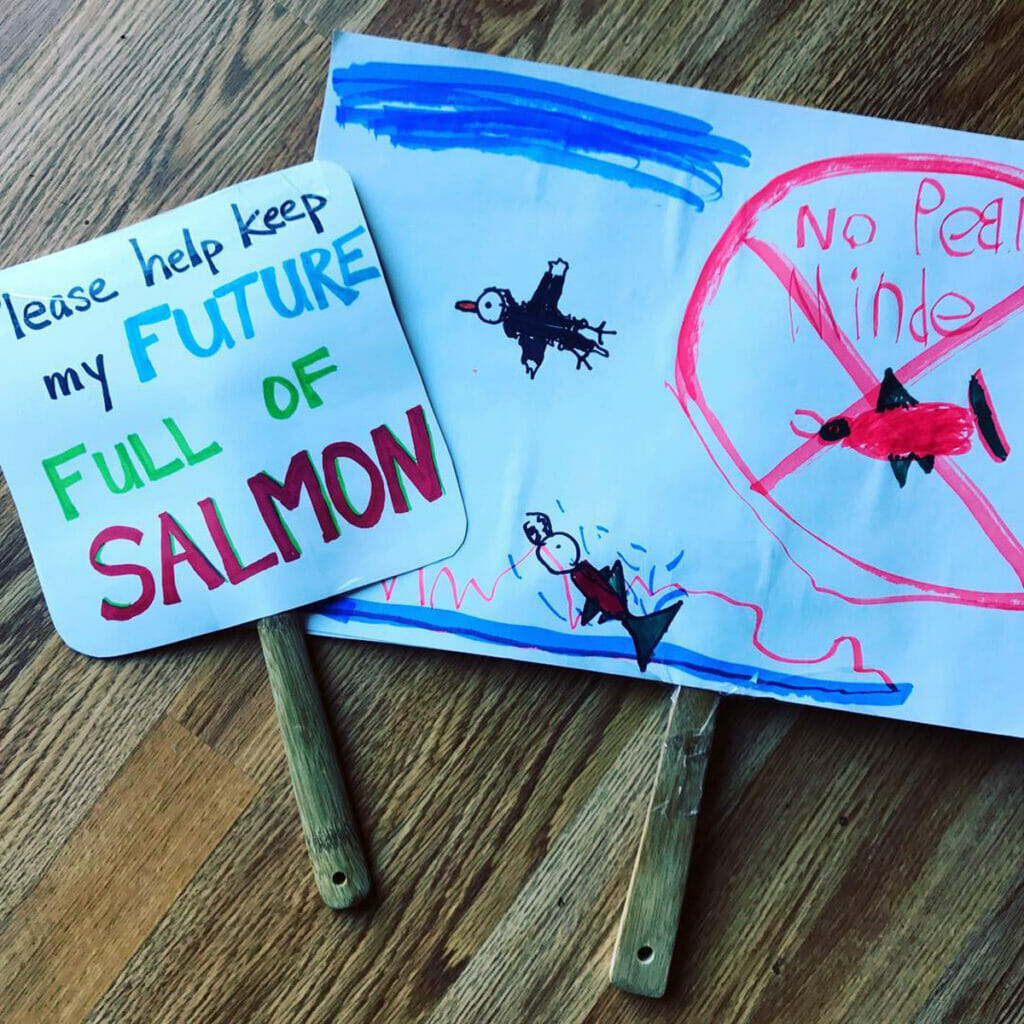

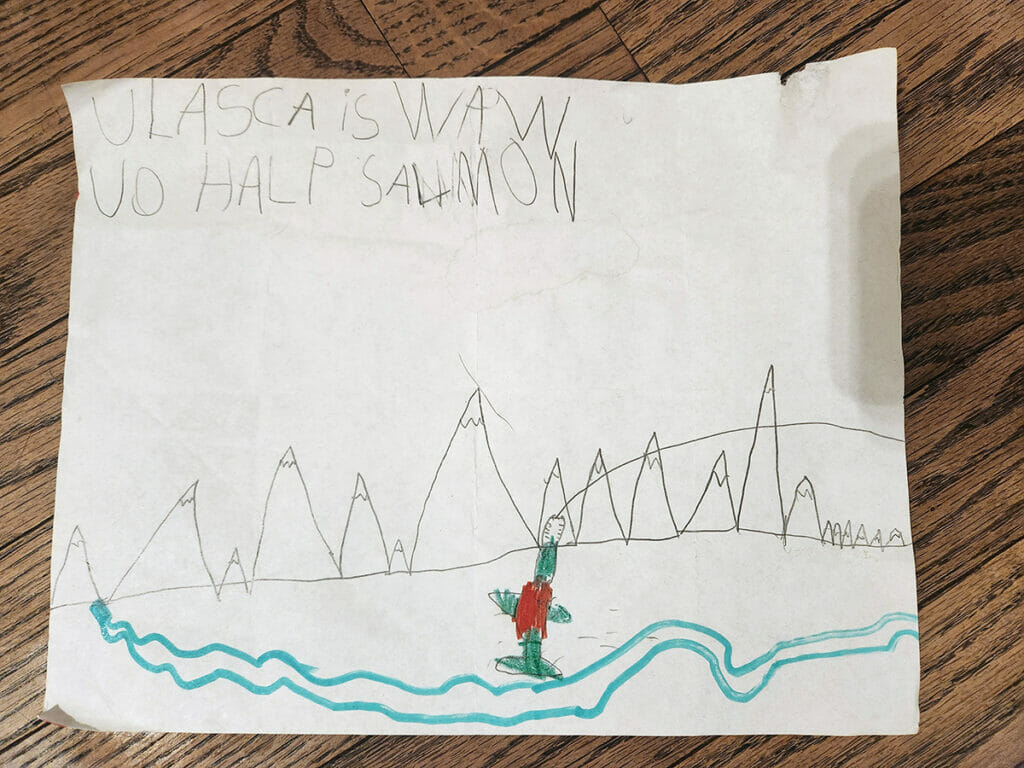

Presidents changed, the kids grew, our son started school. At 6 years old, he was starting to get the importance of wild salmon in wild places it:

For me, 2017 and 2018 were years of red-eye flights, pumping breastmilk in quiet corners of airports, endless numbers of phone calls. In 2019, the EPA’s proposed protections for Bristol Bay were withdrawn. This time, our side challenges that decision in court, but in the meantime, Pebble moved forward.

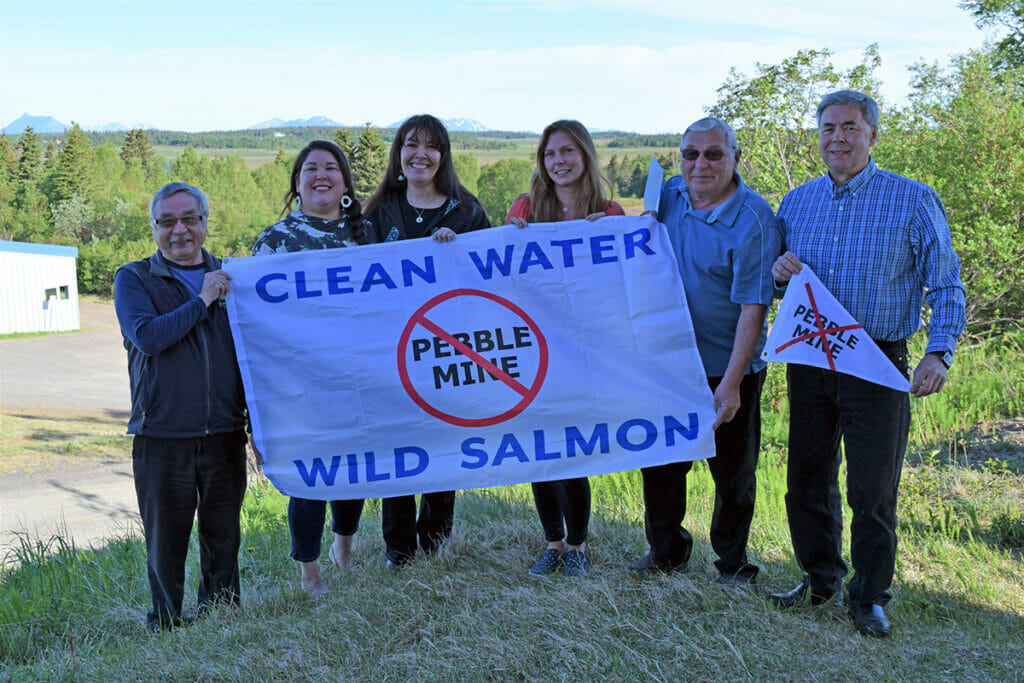

Tribes, anglers and hunters and businesses around the country spoke up, all aiming to pull back the rosy lenses through which the Pebble Partnership wanted the world to see their mine.

The partnership applied for a major permit needed to build its mine. The plans revealed that the mine would involve destruction of dozens of miles of rivers and thousands of acres of wetlands. The permit was fast tracked.

More hearings. More overwhelming opposition to the mine and the crystal-clear science that this mine would harm critical salmon habitat.

Then, after months of hearing that hope was foolish, common sense prevailed. The federal permit applications were denied.

“We did it!” I shouted in the early-morning dark as our kids were waking up for virtual school. Our son, then 9, gave enthusiastic high fives. He knew the thrill of catching salmon and trout. He kind of understood that when his mom and dad spend long days on their computers, that they are somehow helping the fish he loves to catch.

Next came an innocent and enthusiastic question from our 5-year-old daughter: “Mommy, does this mean you don’t have to work anymore?”

“Not yet, my dear.” I replied. “If we want salmon to be around for when you grow up, we can’t rest quite yet.”

This was a milestone, but a new mine plan could be proposed. We needed that little used provision of the Clean Water Act that Tribes and commercial and sportfishing groups asked for long ago. Something that would provide certainty that can help keep clean water, fish, recreation opportunities, and food around for a long time.

That lawsuit we had filed back in 2019 had moved through the courts, and another improbable victory came our way. Following an appeals court ruling in our favor, the EPA reissued and updated the proposed protections. Yes! Another milestone to celebrate, leading to another round of hearings, phone calls and testimony.

Both our kids are in elementary school now, so they don’t come along as often. Colleagues’ kids have grown and left for college, others are taking over their parents or grandparents fishing boats and lodges. Brand new babies are bounced on laps during video calls.

In December, the EPA advanced protections for Bristol Bay from proposed to recommended, marking a significant milestone in the effort, just one step away from finalizing safeguards that were requested more than 12 years ago.

Four million comments over 12 years in support of protection. Thousands of pages of scientific documentation on the impacts the proposed mine will have on salmon. Thousands of local people fighting tirelessly to protect their way of life from an unwanted mine—many who first heard about the Pebble Mine when they were young, when parents and grandparents brought them to community meetings.

Our son, with whom I was pregnant when Alaskans first asked the EPA to get involved, is now busy with soccer practice, homework and friends. He loves to fish, bike and ski. He can drive our boat. The teenage years are approaching.

After this latest win, the celebration was more muted. When our son heard the news after long day of school, we got a fairly nonchalant, “Cool.” Which, reading between the lines of a pre-teen, means, “I’m kinda sick of hearing about the Pebble Mine.”

Me too, my son. A lot of us are.

Let’s get these protections across the finish line so that the many kids who have grown up under the shadow of a giant mine can embrace a bright, fish-filled future for Bristol Bay.

I can say with confidence that raising a young family while juggling a demanding job, regardless of how meaningful it is, is one of the hardest things I have ever done. The late nights and early mornings. The constant wiggle of worry: is my work messing up my kids? Are the kids impacting my work?

Is it worth it? I hope so.

I hope they remember the kitchen mini-celebrations more than the times I’ve said, “I can play after I am done with one more email.” I hope they remember giant rooms filled with people who have overcome their differences to collectively speak up for something they love more than hours of boring meetings. I hope they remember our weekends on the river, not my lack of patience on a Friday evening while we scrambled to pack our gear and wrap up work.

Our kids are just beginning to realize how lucky they are to live amongst wild rivers full of fish, and spectacular landscapes. My hope is that by having a front row seat in this battle, they don’t take them for granted and understand the importance of jumping in to take care of the places you care about.