When it comes to long-term restoration projects, Erin Rodgers measures the passage of time not so much by clocks and calendars, but by kids.

So it was when recently recounting a multi-year project on Vermont’s Mettawee River; Rodgers thought back to two big life moments to help her remember the project’s pace.

“The Mettawee is one of those funny projects where I base a lot of it on when my two kids were born,” said Rodgers, a project manager for Trout Unlimited’s Northeast Coldwater Habitat Restoration Program. “I’ve got various pictures of me on site with children strapped to me.”

In 2015, the year Rodgers’ daughter Alice was born, the Forest Service started working on in-stream habitat in the Mettawee’s headwaters on the Green Mountain National Forest.

Then came the big year of 2017.

That’s the year her son, Simon, was born. It was also the year that TU and the U.S. Forest teamed up to take out the first two of six barriers blocking fish passage on the Lake Champlain tributary, which has been designated as one of TU’s Priority Waters in Vermont. TU’s shared Priority Waters provide the foundation of a strategic blueprint to protect, restore and reconnect wild and native trout and salmon waters across the U.S.

The final barrier on the Mettawee came out in 2023, wrapping up the original goal of opening up the river from its headwaters in the Green Mountain National Forest all the way to Lake Champlain.

“It was more intensive than a lot of our projects and I for sure spent a lot more time in the area than on many of our projects,” Rodgers said. “There’s always something more that can be done to continue to improve the health of the watershed. But to be able to string six projects together like that is really hard, especially in New England.”

All about partnerships

Although the Forest Service was a key partner, none of the barriers were actually on Forest Service land. But the partnership made sense because of the connectivity between the stream on private land and within the Green Mountain National Forest.

“Every watershed in the forest is an opportunity to protect and enhance aquatic resources,” said Jeremy Mears, a fisheries biologist with the Forest Service in Vermont. “These areas provide clean water as well as cold water refugia for native fish species. Additionally, we are creating infrastructure resiliency in the face of increasingly damaging storm events. We also are maintaining access for the public to use these lands.”

About the fishery

The river’s productivity made it a priority. The system’s headwaters feature robust populations of native brook trout. Rainbow and brown trout are the dominant species in the river’s middle and lower stretches, though there are also some brook trout in those reaches.

“The Mettawee provides an opportunity for multiple species of trout but is also a fantastic native brook trout stream,” Mears said. “Now that barriers to passage have been removed it will be interesting to see what that does for the fishery, and fish populations.

“This will help protect trout from the warming water temperatures by providing access to colder upstream waters.”

Permanent protection on Forest Service land and an established riparian buffer as the stream passes through the picturesque community of Dorset Hollow added to the appeal.

Funding is critical

A Joint Chiefs grant from the Forest Service and the National Resources Conservation Service provided some funding, but most of the funding was from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service’s Lake Champlain Basin Program and Vermont’s Clean Water Act funding.

Mears said the work fell under at Joint Chief’s Project called Poultney-Mettawee Watershed Restoration Project. Other partners included the Natural Resources Conservation Service, Poultney Mettawee Natural Resources Conservation District, TU’s Southwest Vermont Chapter, Vermont Fish & Wildlife, USFWS Partners for Fish &Wildlife, and Vermont DEC River Management Program.

The recent agreement between TU and the Forest Service to fund up to $40 million in infrastructure projects over a five-year period also provided some money for the final phase of the work in 2023, Rodgers said. That agreement was made possible by the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law.

Rodgers put the ballpark price for all that work at between $1.3 million and $1.5 million.

Progress to reconnection

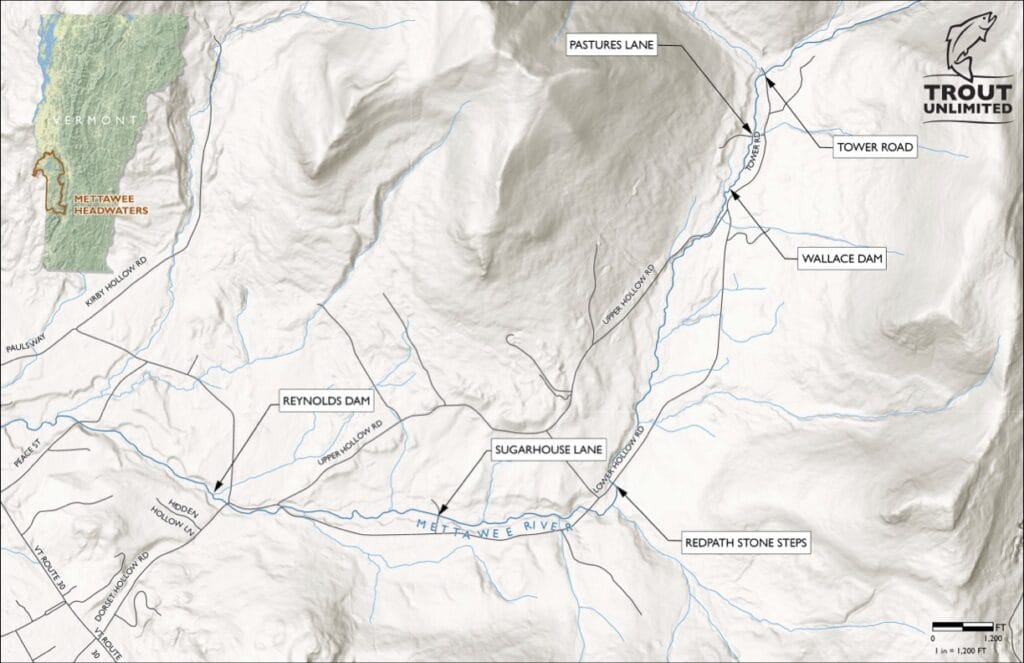

The uppermost culverts, at Towers Road and Pastures Lane, both were replaced in 2017. The lower barriers followed over the next few years, with a break in work during the Covid pandemic.

There were a few unique challenges.

In one case, a landowner hoped to preserve a unique spillway.

“The family loved it and didn’t want it touched,” Rodgers said.

The structure was able to be saved even as the main dam was removed.

In another case, work revealed a surprise dam buried by silt just 50 feet above another dam.

“There was no record of that dam on anyone’s deeds,” Rodgers said, laughing. “We had no answers as to why there might be two dams just 50 feet apart. Maybe someone had built it to make a swimming hole or something ridiculous like that.

“Fun things happen when you work on a landscape scale.”

At times the effort required installation of temporary bridges so crews could reach project sites — and so area residents could reach their properties.

The final barrier, at Sugarhouse Lane, came out in 2023.

“It was a weird one,” Rogers said. “There was a bridge built on top of the dam, but no one could tell us if the dam was built and the bridge was put on it later, or if the dam was built so the bridge could be put on it.”

Regardless, the plunge pool below the dam had scoured the streambed upstream, so a large portion of the dam was not supported by anything structural.

“The structure was quite unsound, one of those private structures that, until someone has to pay attention to it, nobody understands just how bad it is,” Rodgers said. “The construction guys were like, ‘We don’t know if we want to take an excavator over this bridge,’ so that’s one where we installed a temporary bridge.”

Beyond barriers

In addition to replacing the barriers with bridges, crews also completed some in-stream restoration to improve fish habitat, which is something Rodgers and her teams have been accomplishing across the region.

“Erin and her crew have accomplished miles of strategic wood addition on both the north and south half of the Green Mountain National Forest,” Mears said. “We currently have work scheduled on the north half to work with TU to begin a larger riparian restoration. We all wear many hats and the relationship works well.”

Rodgers said she thinks the project is a great example of what can be accomplished on a watershed scale.

“I really appreciated the more focused approach we were able to take in that area,” she said. “It was a lot of effort, for sure, but one that I would like to see us replicate in a lot more places over time.”