The room is full for the banquet. I first came across the Narragansett chapter of Trout Unlimited seven or eight years ago, when a few frustrated members contacted me and complained that the chapter was assisting the state in stocking over native fish in violation of TU policy. After a time, the chapter stopped, but the frustrated members, dedicated conservationists all, formed a new organization, Protect Rhode Island Brook Trout (PRIBT).

Earlier in the day I did a short tour of the Wood River with Glenn Place, the President of the chapter; Brian O’Connor, one of the founders of PRIBT; Corey Pelletier, a fisheries biologist with the state; and Todd Corayer, an outdoor writer.

Corey is a young guy with a soul patch—and a passion for brook trout recovery. Thanks to an Embrace A Stream grant, and the chapter’s habitat assessment group, Corey was able to monitor water temperatures throughout the Wood River system. We now know where the cold water refuges persist, and where dams and their impoundments make the water lethally warm for native brook trout.

More than 240 dams bisect the Wood River and its tributaries. Most of them unused, unneeded, and a liability for people living downstream. Corey found one that has no constituency, and no users, and that would open up a cold water stream with a thriving brook trout population. We will help him to make its removal a reality. We don’t need to remove all these dams, just the ones that offer the most promise for brook trout expansion and restoration.

Brian is a great woodworker. I bought two of his handmade canoe paddles, and will likely never allow myself or my sons to let them touch the water, much less scrape a stream bottom. He has forgotten more about the Wood than most will ever know. He told me about a section he has fished for 40 years where brook trout could always be found but in two recent drought years, “they simply disappeared.” Brian fears that we are too late—that the warmer summer temperatures and periodic droughts may have taken too significant a toll on native brookies. His hope for the future, he told me, depends on the day. Today at least, he was hopeful.

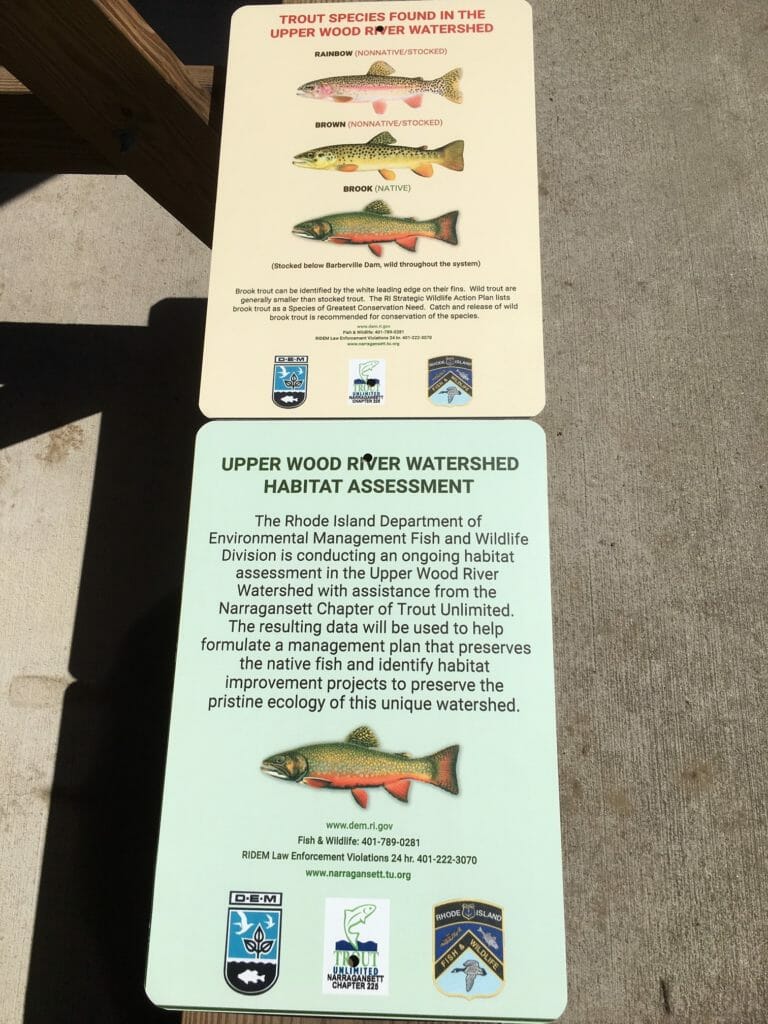

Glenn, whose most recent chapter newsletter warned it would be short because he was busy—it was six pages—is a relentless optimist and a great leader. He commissioned signs posted along the Wood River to encourage anglers to release native brookies. Those could presage a catch and release section or two along the river, and impress upon anglers the need to support recovery of native brookies by removing dams, and not stocking over native brook trout.

All of us who care about trout and salmon, and the rivers upon which they depend, face three central challenges.

The first is to connect our trout work to broader societal issues. For example, when we protect the land around a stream at higher elevation, we reduce water filtration costs. When we reconnect a river by getting rid of unneeded dams, replace undersize culverts with bridges, or allow a river to reach its floodplain, we reduce the effects of flooding on downstream communities. When we restore rivers, we create family wage jobs and reduce the need to stock expensive and dumb hatchery fish.

Second, we need to get younger and more diverse. America is changing. If we don’t change, too, we may find that future leaders do not support our conservation work. Thirty percent of fly-anglers are women. Twenty percent are minorities. Our members and supporters should reflect those demographics.

As I looked across the room, I realized that a not insignificant percentage of the people who care about trout in the state of Rhode Island—native, wild, or hatchery—were probably in attendance. The third challenge is not to splinter into factions. About 10 percent of America fishes. Maybe two percent fly fishes. We can argue, and bicker, and disagree, but as angler-conservationists, we cannot afford circular firing squads. Conservation is generally a game of incremental progress. Working together makes progress a lot easier.

I walked off the river with Todd and asked what he thought. He replied, “Today was a good day for the Wood River.” I agree. Let’s take out a few of those deadbeat dams, and see what we can make happen.

Chris Wood is the president and CEO of Trout Unlimited.