A TU chapter partners with the California Department of Fish and Wildlife to search for pure Kern River rainbow trout in its spectacular native range

In the summer of 2022, Jim Correa, president of TU’s Central Sierra Chapter, backpacked 30 miles with a 35-pound pack into one of the most remote places in the Lower 48.

His goal was to find a rare, native trout that might not even be there.

This is an impressive accomplishment for someone in their physical prime. Correa is in his 70s, a few years into retirement after a Sisyphean career as a large animal vet.

Strap 35 pounds to your back and see if you can hike a mile on flat ground. And do it for the love of science, with house money betting you won’t find what you are looking for.

Yet when two fish biologists with the California Department of Fish and Wildlife (CDFW) asked Correa if he could recruit a couple of hardcore backpackers, who could double as decent fisherfolk, to help search the high country of the southern Sierra for remnant Kern River rainbow trout, Correa said sure – and volunteered himself.

Survivors of the Ice Age

The oceans of ice that covered much of North America during the last Ice Age plowed the Sierra Nevada range into a fantastical landscape. In much of the range, endemic trout – cousins of the ubiquitous coastal rainbow — were extirpated during that era.

But in the southern third of the Sierra, the glaciation was less severe. Three subspecies of rainbow trout – the Kern River rainbow, the California golden trout, and the Little Kern golden trout – were able to persist in the high country.

TU is working in dozens of watersheds to protect and restore native trout populations in California. For many years in the upper south fork of the Kern River, for example, TU has led meadow restoration and fish passage projects to bolster golden trout populations in their small native range.

But until late July of last year, when Correa, his hard-charging friend Derek Daley, and CDFW tech Richard Vega backpacked into two isolated streams in Sequoia National Park, TU had not done any field work in Kern River tributaries west of the mainstem.

Pure Kern River rainbows are now rare enough that CDFW considers them a Species of Special Concern, while the US Fish and Wildlife Service determined them a candidate for listing under the Endangered Species Act.

Previous searches for pure Kern River ‘bows found but one pure population, and CDFW hoped to discover others, where they might still exist upstream of impassable barriers. CDFW’s research suggested the two streams targeted by Correa and his partners might hold trout, but there was no way to know for sure until that hypothesis could be field-tested.

Fly fishing for science

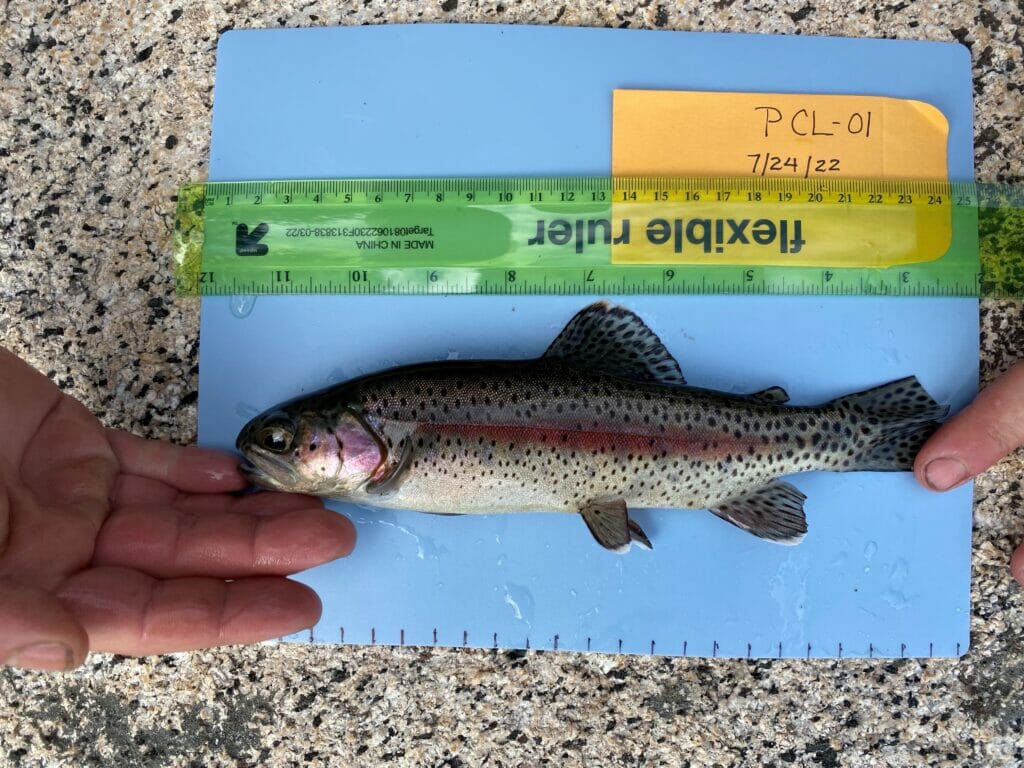

Correa and his team were commissioned to survey the two streams and “sample” them for trout by using the latest technology – fly fishing gear. They would then collect data including fish length, photos, and a ¼” clip from their caudal fin to be tested for genetic typing.

The Upper Kern Basin and the Kern Kaweah Divide is, says Correa, “an absolutely stunning scenic region.” The final ten miles of country they crossed to get to the target streams were very isolated, and Correa’s party saw no other humans during several days of surveying and collecting data.

Much of the High Sierra was trout-less prior to the stocking efforts of wildlife agencies, miners and shepherds over the past 150 years. But if the Correa party found trout, the fish would probably be remnant natives that had not been ferried there by humans.

Find trout they did. Small wild rainbows with exquisite colors and markings vigorously supported the research.

Stable, sunny conditions prevailed while the research team “sampled.” But over the final two days, as the party packed out, the weather gods turned capricious. A massive storm pounded the southern Sierra, washing out portions of the trails the team were following.

You might imagine Correa would have upped the pace of his retreat somewhat. Nope. Correa loves the mountains in all their moods. He maintained his slow-but-steady tromp – and continued to “sample” fishy looking waters as he hiked.

On the final night, due to his diligence in “sampling,” Correa had not caught up to the rest of the party when darkness fell, so he bivouacked solo as the storm raged around him. He met up with his mates the next day at the trailhead.

Sometime this year, we should see the results of the genetic testing of the fish Correa and his mates found deep in the southern Sierra. With any luck, they’ll be pure Kern River rainbows, tucked away in remote public lands that previous generations of Americans had the foresight to permanently protect.

As with much of TU’s work, this Kern River rainbow research effort was made possible by partnership. Ken Johnson and Tracy Purpuro, fish biologists with CDFW’s Region 4, led the work to identify the survey sites and obtain the requisite permits to do this work in Sequoia National Park. TU’s Central Sierra Chapter contributed manpower for surveying and “sampling,” and covered the $2700 cost of hiring an outfitter to pack most of their food into the backcountry, so the party would not have to carry more than the equivalent of four full gallon-jugs of water per person as they hiked.