Humans are coming to grips with the damage we’ve done … and the need to repair it

Even in New Mexico, a state so over-endowed with emptiness that one can find a place to hide a body almost anywhere, Gila country is about the loneliest place imaginable.

The closer you get, as I realized on my most recent visit, the more you feel the crush of isolation. On the Plains of San Augustin, plumes of dust rising off a distant truck aroused mini-fits of panic, causing me to check my fuel gauge seemingly every other minute. Road signs wagged on their posts, ravens banked to hold position above the vast yellow plains. Everything seemed at war with the wind.

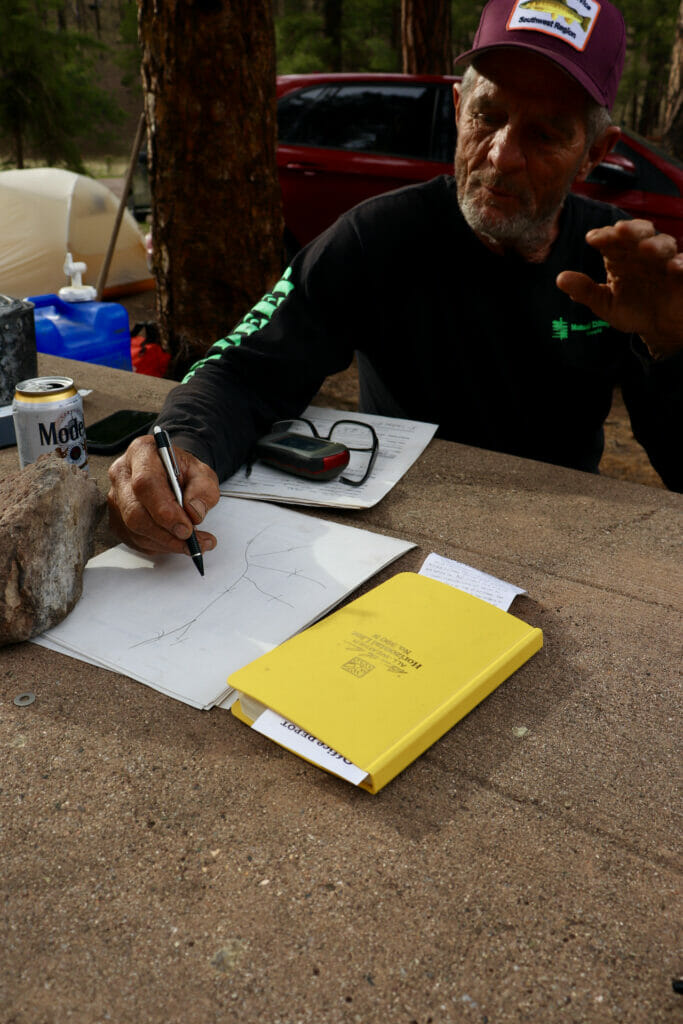

The purpose of my trip was a TU habitat assessment of Willow Creek, located in the footprint of the largest wildfire in New Mexico history. Impacted by high-severity burning in its headwaters and heavy post-fire debris flows, Willow was the focus of efforts to recover Gila trout populations beginning in 2013. There was good early momentum, the stocking of catchable Gilas and the construction of a non-native fish barrier in 2016. A decade later, aspen trees are starting to pop up on north-sloping burn scars.

Willow Creek’s Gila populations have nevertheless declined steadily over the years. As a result of fire-denuded slopes dumping sand and gravel throughout an incised stream channel, pool habitat is scarce. Without pools, there’s no temperature refuge in the winter or on hot summer days, especially for larger, sexually-mature fish.

The culprit is climate-induced reductions in precipitation, especially snow. With a normal snowfall, spring snowmelt flows with sufficient power and duration to scour pools and deposit sediment in a manner that generally rebuilds a healthy channel. In recent years, however, most of Willow Creek’s high flow events happen during the summer monsoon season. Short pulses of high flow merely lift bed material from one place and drop it not far downstream, often in a pool.

Until the region gets a thick winter or two, ideally in succession, Gila trout restoration will languish on Willow Creek.

Even in that event, broad-scale human intervention will be required to ensure that Gilas won’t blink out in other creeks where they live. Stocks of fish must be grown in hatcheries. Stream channels must be reshaped, their riparian zones reconnected so that trout and other aquatic organisms can absorb future shocks and disturbances. Decent amounts of money must be spent on establishing such resilience.

Huddled in my sleeping bag, I remembered for the umpteenth time that wolves—or Gila trout, elk, turkeys or any of the other critters that make an exciting camping story—are merely the sexy surface of the nature we profess to care about. They thrive to the extent that their habitat thrives. We must help our streams and forests recover their function, which will call for appearances from a supporting cast of organisms.

The general takeaway from the Willow Creek story—that humans must direct more time and energy to fixing what we broke—is beginning to get the attention it deserves, particularly in the context of the planet’s biodiversity crisis. The popular notion that ecosystems will autocorrect if left alone, while absolutely true, is of little value to the Gila trout, given its weakening foothold in climate-damaged watersheds and the consequently short time frame for recovery. That Gilas must also surmount competition from non-native brown and rainbow trout underlines how restoration must be prioritized where conditions demand.

I’m thrilled at the renewed optimism around protecting and enhancing biodiversity, and I particularly appreciate how the mission is being communicated. There’s less moralizing and romance, and more cold-eyed acknowledging of our nuts and bolts relationship with nature. We’re referring to our waters, skies, farm fields and forests as the infrastructure it is. I like that Willow Creek can share a stage with Flint, Michigan’s drinking water system.

As we tackle environmental collapse, humanity’s role is being expressed in more inclusive terms, in terms of who will lead the effort to reconstruct a healthy environment, who will have access to it, but also in terms of our biotic citizenship. To succeed, we’ll need underserved communities at the table, especially Indigenous and rural communities with their expertise at stewarding wild spaces. Importantly though, we’ll have to tie our own health to the land’s.

On my first night at Willow Creek, a pack of Mexican gray wolves set up down the canyon and howled through much of the night. It was one of the coolest things I’d ever experienced, wolves in the wild! How many stars had to align for me to witness that?

Huddled in my sleeping bag, I remembered for the umpteenth time that wolves—or Gila trout, elk, turkeys or any of the other critters that make an exciting camping story—are merely the sexy surface of the nature we profess to care about. They thrive to the extent that their habitat thrives. We must help our streams and forests recover their function, which will call for appearances from a supporting cast of organisms.

We need pollinators, fertilizers, and dispersers of seed to be distributed broadly throughout our ecosystems; the grass and gophers, the soil and the microbes that keep it alive. In our quest for inclusivity, let’s not forget that biodiversity is more than a benefit to which humans should have access. It’s the wolf, its food, its food’s food, and its food’s food’s food.

It’s infrastructure, and as it goes so do we.

Toner Mitchell is TU’s water and habitat coordinator for New Mexico.