On Oregon’s North Coast rivers, NOAA restoration investments are helping reconnect critical habitat for salmon and farmers.

When many of us picture barriers to fish migration, we often think of dams and perched culverts preventing salmon, steelhead and other native species from reaching spawning and rearing habitat, off-channel refuges from high flows or sources of clean, cold water.

But further downstream, in the estuaries and tidal wetlands of coastal watersheds, old or failing tide gates can also keep fish from moving up and downstream to reach important habitat, prevent smolts from successfully migrating out to the ocean and threaten the ability of farmers and communities to manage flooding and agricultural production.

On Oregon’s North Coast, the Salmon SuperHwy partners are working to reconnect almost 180 miles of blocked historic salmon, steelhead and lamprey habitat. They’ve identified a portfolio of 93 restoration projects needed to meet this ambitious goal and have already opened 132 miles of habitat across six river basins draining into the Tillamook and Nestucca Bays.

Many of these projects replaced failing or undersized culverts and improved roads and bridges for local communities. But this summer, with support from the NOAA Restoration Center, the Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife, the Siuslaw National Forest and other local partners, the Salmon SuperHwy will also replace a failing tide gate.

This improvement will give native fish access to exceptional rearing habitat and will also help a local farmer better protect their land from flooding.

What is a tide gate?

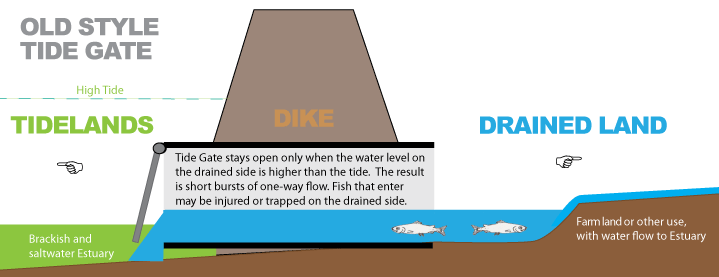

A tide gate is a “door” on a culvert or channel through a dike, levee or road prism that separates a body of fresh water at its upstream end from the salt water on its downstream (tidal) end.

The mechanism is simple; when the tide is low and there is no outside pressure on the tide gate, water flowing from upstream is able to push the door open and flow into the tidal area. When the tide rises, pressure builds on the door of the tide gate and closes it, ensuring that little to no saltwater travels upstream into the freshwater system.

Typically, tide gates are found where farm drainages meet a brackish water source in or near a watershed’s estuary. By installing a tide gate at these locations, farmers are able to drain their fields while protecting their crops or pastures by keeping saltwater from moving upstream during high tides. Coastal communities also use tide gates to prevent flooding in towns and developed areas.

However, tide gates are sometimes located on streams or wetlands that could provide great aquatic habitat upstream for salmon, steelhead and other native fish.

Updating tide gates

Many tide gates, such as the one pictured in the illustration above, pose significant drawbacks for fish. Most were installed years ago when low-lying coastal wetlands were drained to create farmland or support development. Over the years, many have failed and no longer have a functioning door or an intact culvert. When this happens, farm and agricultural production is jeopardized, and fish migration can be blocked.

Many of these old-style tide gates greatly reduce fish passage to potential spawning and rearing habitat upstream of tidal waters. Recognizing the importance of this blocked habitat, NOAA has invested federal funding into replacing older or failing tide gates with newer options that improve fish passage while continuing to protect previously drained land adjacent to a stream or tidal wetland.

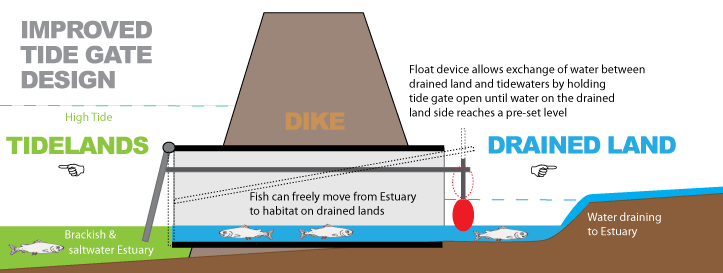

This updated tide gate incorporates an upstream float that can be set at a specific height to allow a pre-determined amount of flow through the tide gate before it fully opens or closes. Adjusted seasonally this allows for longer fish passage windows during key times for resident fish and peak spawning runs of anadromous fish.

In some places along the Oregon Coast, Muted Tidal Regulators (MTR), a newer tide gate design, are used to replace failing tide gates.

Unlike other options, MTRs offer adjustability of the tide gates throughout the year depending on whether it is the wet or dry season. Unlike other gates, which default to a closed position, the MTR is held open by a counterweight. This ensures that fish passage is accessible when it is most important, while still giving farmers the ability to precisely manage the water on their land throughout the year.

The Esther Creek tide gate project

This summer, with support from NOAA and others, the Salmon SuperHwy will replace an old tide gate blocking fish passage on Esther Creek, a tributary to the Tillamook River. An MTR design will be used and be accompanied by a water management plan with the landowner.

This project, like many others, is multiple years in the making. The current tide gate on Esther Creek has a rusted door that no longer functions properly. It not only blocks fish passage, but it also puts the farmer’s field at risk of saltwater inundation. A new tide gate will solve both problems.

The water management plan is an agreement between NOAA and the landowner. After an extensive hydrologic analysis, the plan identifies optimal flow levels and velocity for fish passage throughout the year. It provides an annual schedule for tide gate adjustments that will optimize benefits for migrating salmon, steelhead and other native fish while continuing to prevent flooding.

Stay tuned for updates

Up and down the coast, anglers, commercial fisherman, farmers and landowners are realizing that improving and updating tide gates is a great opportunity for fish and local communities and a perfect complement to habitat restoration and reconnection efforts underway further upstream in coastal watersheds.

We’re thrilled to be working with NOAA and our partners on the Esther Creek project. Stay tuned for updates as the work gets underway this summer. We’ll be sharing progress on the Salmon SuperHwy’s Instagram and Facebook accounts.

Learn More

Want to learn more about NOAA’s work on tide gates? Check out Tide Gates: Operation, Fish Passage and Recommendations for Their Upgrade or Removal on the agency’s site.

Oregon Public Broadcasting also featured a recent story on tide gates: Aging tide gates threaten Oregon’s coast, but replacing them isn’t cheap