Many conservation organizations are great at on-the-ground habitat restoration. Others excel at policy advocacy. Trout Unlimited is one of the few that shine at both.

Our recipe for success is simple. We take the results and good will generated by the partnerships, relationships, and in many cases, friendships created through our restoration work, and use that to leverage positive policy outcomes.

That formula is playing out in the Great Lakes today. More than 20 percent of the world’s freshwater is contained within the boundaries of the Great Lakes. The Great Lakes support about 140 native fish species; and about 40 percent of them are threatened or endangered. They are in peril from threats as diverse as Asian carp to typical traditional urbanization and development.

On river systems such as the Rogue and Grand in Michigan, TU has engaged more than 6,500 kids in tree-plantings, and the construction of rain-gardens and bio-swale constructions to slow and minimize run-off to the river. More than 80 high school kids have been employed by the so-called Green Team, a workforce that helps to maintain those projects as summer jobs. We work with hundreds of Girl Scouts each year to teach girls about river ecology through STREAM Girls.

Working with the Huron-Manistee National Forest, we helped to restore a river bank below Tippy Dam—an area that receives the highest angler pressure in the state. Using native plants, hardened access points, and other techniques, we helped to both improve river access and the health of the river. Elsewhere on the forest, we completed more than 10 projects reconnecting more than 40 miles of river in the forest over the past two years.

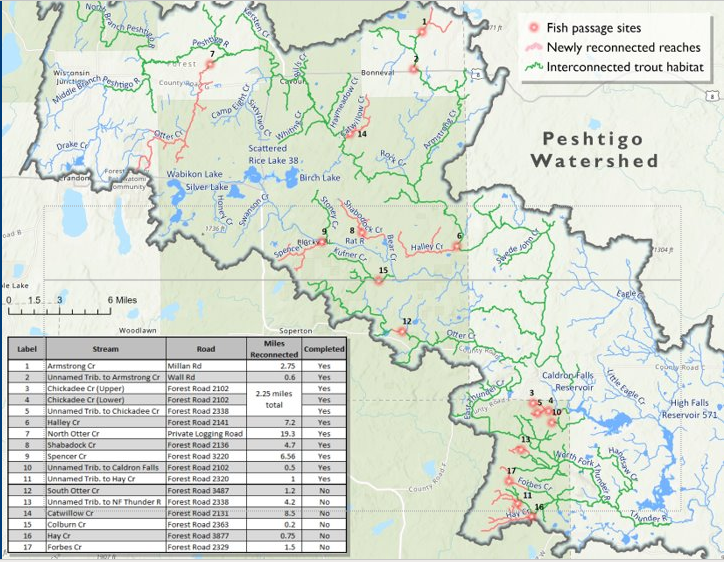

On the Peshtigo watershed in northeast Wisconsin’s Chequamegon-Nicolet National Forest, TU reconnected over 80 miles of tributary streams that kept fish from passing in drought and posed a risk to transportation infrastructure during flooding. After restoration, large brook trout now migrate from the mainstem river when it warms, and head for the now accessible, cooler and higher elevation streams.

I could continue to elaborate on our restoration accomplishments in the Great Lakes. As every angler knows, river systems are remarkably resilient, and if we give them half a chance, they will respond. What makes the Great Lakes work so significant is how we use those restoration gains to leverage policy goals.

Consider the Great Lakes Restoration Initiative. Proposed by President Bush and continued by President Obama, the initiative is one of the more ambitious efforts to maintain and recover the health of the Great Lakes. We have used this funding to plant more than 17,000 trees with the Girl Scouts, Forest Service, and other partners on the Rogue River, for example—purifying more than 1.5 million gallons of rainwater that would have otherwise contributed to stream-bank erosion.

The White House proposed eliminating the Great Lakes Restoration Initiative in 2017. That’s when our Great Lakes organizer, Taylor Ridderbusch, went to work. Taylor arranged to fly volunteers from the Rogue, Peshtigo, Manistee watersheds back to Washington, D.C., to meet with their members of Congress and explain the value of the Great Lakes Restoration Initiative. I saw Taylor in D.C. so often, that I jokingly asked if he had moved to the nation’s capital.

Taylor’s work was successful, and we restored full funding for the initiative for the two years the administration proposed eliminating it. Members of Congress don’t want to hear from fast talking guys from New Jersey like me when it comes to their in-state issues. Taylor’s ability to put local faces and local voters in front of local elected-officials was a huge reason why the Great Lakes Restoration Initiative survives today.

The same case can be made for a myriad of other policy issues that affect the Great Lakes. Whether it is the invasion of Asian carp, ballast water discharge, or urbanization and development—we can fix what ails the Great Lakes. But only if enough constituents tell their elected leaders they care. That is the purpose of the Case for the Great Lakes—drafted by our volunteer leaders (and Taylor) it makes the case for why, and how, we can save the Great Lakes–what President George W. Bush called a “national treasure.”

The Case for the Great Lakes describes the many policy and ecological challenges facing the Great Lakes, and what we need to do about them.

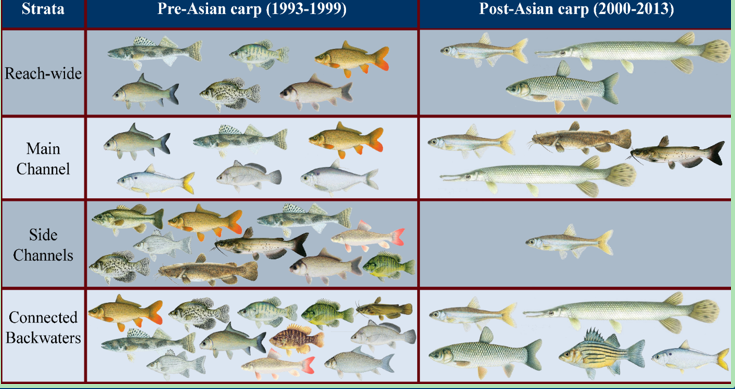

Invasive Asian carp, for example, have yet to reach the Great Lakes, but they are close. These prolific fish completely take over and eliminate native and wild fish (see graphic above). Taylor and our partners have been effective in securing local and congressional support for measures to stop the spread of Asian carp, but we must act quickly before they reach the Great Lakes, and secure the funding needed to stop them.

The Great Lakes Restoration Initiative received a $20 million increase in this year’s federal appropriations bill. Stopping Asian carp is a possibility because of Trout Unlimited’s advocacy.

Please contact me if you want to help us replicate this success with the many other issues that affect the Great Lakes. They are worthy of our best effort.

Chris Wood is the president and CEO of Trout Unlimited. He works from TU’s Arlington, Va.-based headquarters.