Apache and Gila trout face vast new challenges thanks to landscape alterations

What do two 19-year intervals separated by four centuries have in common, and what do the similarities mean for native trout?

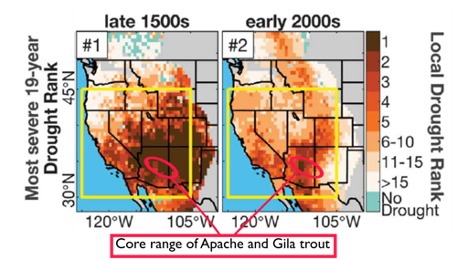

A recent study reconstructed climate for Southwestern North America, including California, Nevada, Arizona and New Mexico, and found the years 1575-1593 and 2000-2018 had the most severe prolonged droughts in the last 1,200 years.

First, the good news. Native southwestern trout have evolved to persist through periods of prolonged drought. There have been 40 prolonged droughts during the study period, and many of those – including the two most severe – have been centered squarely on the core range of Gila and Apache trout. These species live in high-elevation streams in central Arizona and southeastern New Mexico.

Next, the bad news — and unfortunately there is more bad news than good news.

Those Gila and Apache trout in the late 1500s occurred in a landscape that facilitated their adaptation and persistence in the face of drought. Stream habitats were large and interconnected and trout could move within the systems to find the pools to ride out the dry times. Wildfires occurred freely and frequently, burning some habitats but leaving others unburned.

Today’s Gila and Apache trout are not only living through an ongoing prolonged drought, they also face a number of other challenges their ancestors never knew. They have lost habitat to non-native brown trout and rainbow trout, and our attempts to manage that dynamic with fish barriers have broken their habitats into smaller segments more vulnerable to disturbances. The landscape is witnessing severe range-spanning wildfire exacerbated by climate change and 20th century fire suppression policies. In streams where Gila and Apache still persist, warming associated with climate change is slowly eroding the coldwater habitat they require to survive.

Second, these climate changes are also amplifying the current drought. Less precipitation is falling, while warmer temperatures cause plants to use more water and soils to dry faster. The recent study estimates nearly half of the pace and severity of the current drought can be attributed to human causes of climate change.

Finally, the 2000–2018 drought is still ongoing, and our collective sense of what is normal in the Southwest is largely shaped by what was a relatively wet 20th century. We need to adjust to our management to acknowledge that we are past “peak water” in the region.

But the cause is not lost. We value these fish and they can bounce back when given a chance. Trout Unlimited is partnering with Arizona Game and Fish Department, New Mexico Department of Game and Fish, and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service to increase the resiliency of Gila and Apache trout to climate change through strategic planning, reintroduction efforts, and on-the-ground restoration approaches like creating more pool habitat. TU is also working with a diverse coalition of partners on climate change mitigation and adaptation policies. Learn more about climate change impacts to fisheries and TU’s climate change work, including policy proposals and everyday changes you can make to combat climate change at TU’s Climate Change Workgroup page.

Kurt Fesenmeyer is the GIS and Conservation Planning Director for Trout Unlimited’s Science program. He is based out of Boise, Idaho.