In the Great Lakes region, the brook trout is Trout Unlimited’s mascot for a good reason.

This vibrant salmonid is known as a native indicator species, as their ecology requires habitat parameters like river substrate, dissolved oxygen levels, cold water, healthy surrounding forests and connected stream networks for survival and reproduction. If brook trout populations begin to dwindle, this is a sign that something unnatural is affecting the health of the entire system.

Although the Great Lakes are rich in hundreds of tiny stream networks, these networks are often blocked by road crossings throughout the region.

TU’s focus on reconnecting and restoring habitat for brook trout also serves the needs of many Great Lakes riverine species.

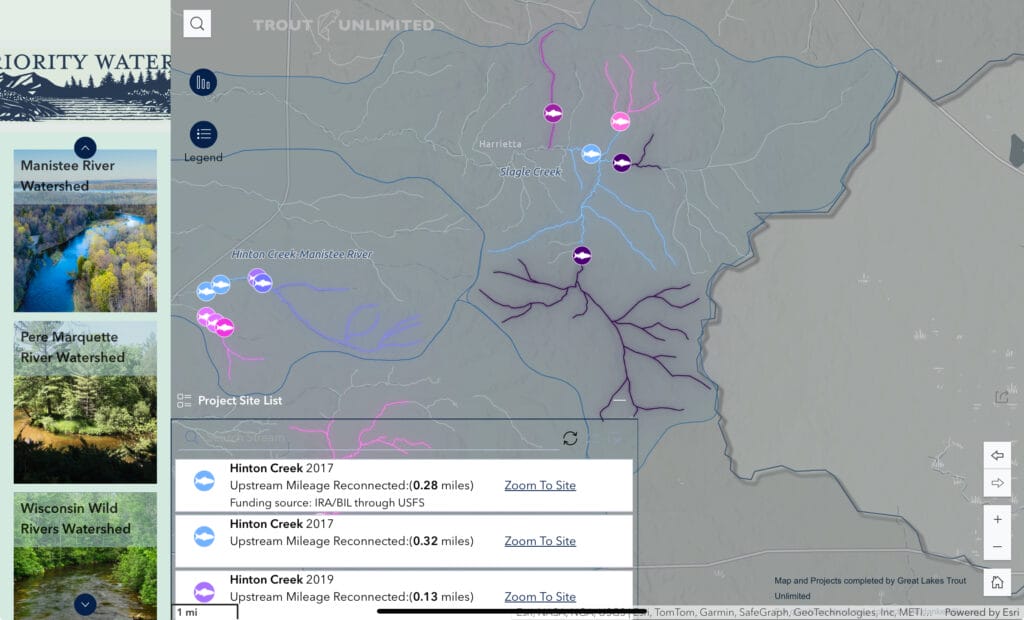

To follow along with the progress of our stream reconnection visit Great lakes TU’s Stream Reconnection Map from Experience Builder.

These miles of reconnected habitat are restored through identification of barriers via data collection then the removal of these barriers at road and stream crossings, culverts and other anthropogenic impacts to streams that inhibit aquatic organism passage.

Geographic Information System (GIS) applications have become essential toward that mission.

Coldwater streams are defined by the Michigan Department of Natural Resources, as streams capable of remaining below 63.5 F year-round, even throughout the hot summer months. Cold water is an ecosystem service made possible by strong groundwater influence, forests and a well-connected stream network.

TU collaborates with agencies and funding partners including US Forest Service, National Oceanic Atmospheric Administration, US Fish and Wildlife Service, National Fish and Wildlife and more to reconnect hundreds of miles of upstream coldwater habitat to aquatic species like brook trout, restoring natural fluvial characteristics and providing climate resilience to freshwater resources.

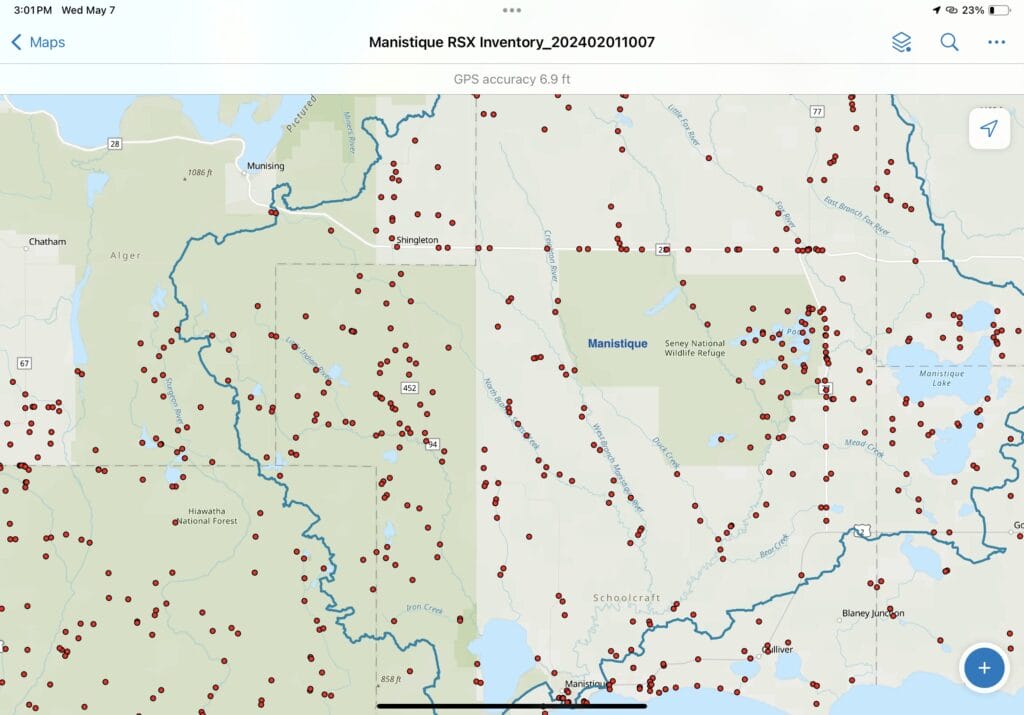

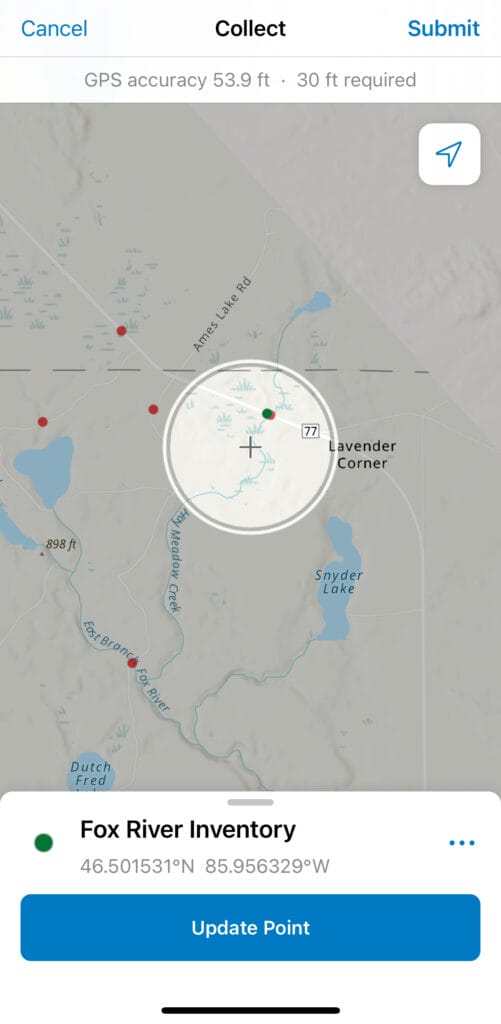

This work is made possible through several ArcGIS field applications, especially data collection in Survey 123.

Field technicians use Survey 123 to collect geomorphic data in order to determine if a stream location acts as a barrier for aquatic species at certain flows.

Field Maps has become an essential tool in recent years for both its offline capabilities and live tracking of progress. The effectiveness of restoration work is monitored through the uses of habitat and biological surveys, including macro-invertebrate surveys, stream temperature measurements and electrofishing surveys focused on native brook trout populations. These data collection efforts are designed and executed through Field Maps for both office and field-based scenarios.

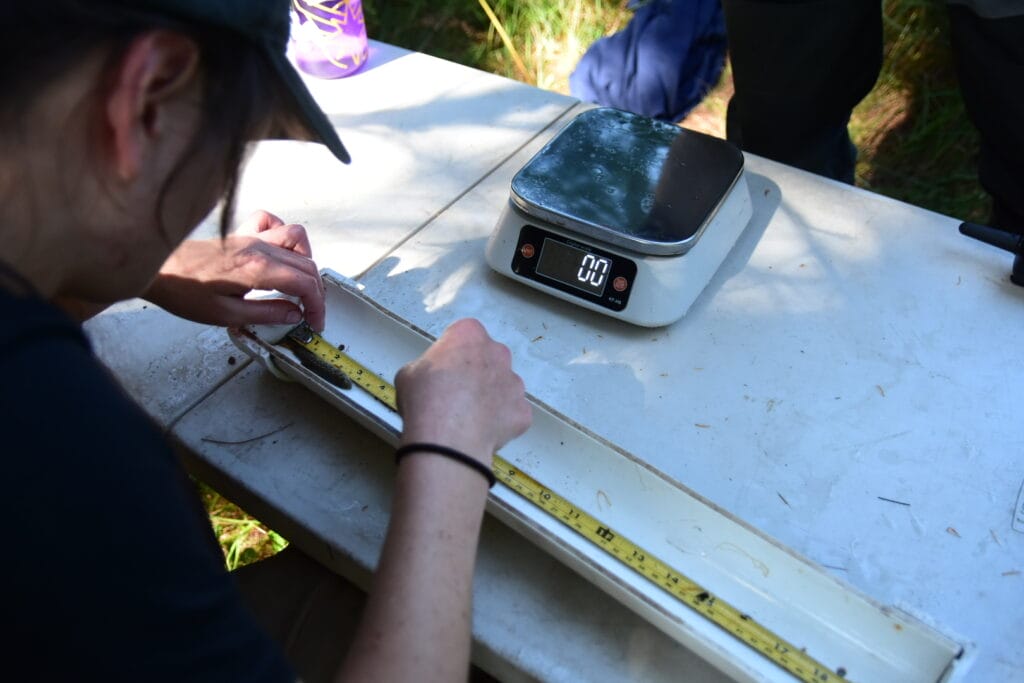

During a day of field work in Northern Michigan, a TU aquatic resource technician will visit sites in the Huron-Manistee National Forest, working to conserve and restore trout populations by identifying barriers to aquatic organism passage.

These white cedar and hemlock forests are littered with treacherous two track roads, where hauling survey gear through rugged hiking trails is often required.

After hiking through the tamarack bush, the technician comes to a stream which they notice is cold to the touch, even on a hot summer’s day. This is due to the strong groundwater influence, and the shaded canopy from the thick forests particular to this region. However, this work site is impeded by a barrier, which not only blocks trout migration, but also effectively increases temperature of water downstream, causing further damage to the ecosystem and other species present like massive mayflies (Hexagenia limbata) and mottled sculpin (Cottus bairdii). Technicians utilize an offline compatible Field-Maps app developed from ESRI’s suite of field applications. The map identifies work sites for the day and links the associated survey defining the style of fieldwork needed.

The Aquatic Barrier Stream Crossing Survey is completed on a daily basis and identifies potential barriers to a stream network. This survey requires many fluvial, erosion and habitat measurements, including flow rate, stream bank-full width and structure width. A completed survey is then submitted on Survey 123 with an immediate barrier score response and sent to an online database to prioritize sites for restoration potential.

Prioritization considers habitat reconnection potential, cost of reconstruction and landowner relationships, among other things. Once the future construction phase is completed, we can continue further up the stream network to find additional barriers to reconnect more habitat.

These restored sites are then monitored by TU staff through recurring biological surveys focusing on fish and macro invertebrate communities, using field maps before and after the construction had taken place. With a completed project we can calculate the connected stream mileage to the next barrier updating our public stream reconnection map.

With these GIS applications we will continue monitoring the progress of TU and our federal and private partners as well as our local chapters and TU members.

By using and sharing these resources we hope to continue to grow our engagement with more people who call these waters home, as well as others who collaborate, advocate and strive for better stream health.

Ideally maps like our stream reconnect resource help present an ethical and sustainable perspective for aquatic ecosystems and human transportation in the Great Lakes region.