Del Rio, Tenn. — Standing atop a newly installed bridge over Wolf Creek, deep in Tennessee’s Cherokee National Forest, Brett Yaw and Sally Petre were both smiling proudly.

Although their professional backgrounds are completely different — Petre is a stream and rivers biologist; Yaw is a civil engineer — they both played key roles in a project that brought together a host of varied partners.

Yaw summed it up.

“You can’t separate watershed health from infrastructure,” said Yaw, a transportation engineer for the U.S. Forest Service.

This new bridge over Wolf Creek, and a similar project on Trail Fork a few miles away, are examples of how Trout Unlimited and its partners are working together on projects that provide those benefits to both infrastructure and ecosystems.

On a recent spring day, Petre and Yaw were among nearly two dozen representatives from many of the groups involved in the restoration projects who gathered at the sites to survey the results of their efforts, and to informally celebrate the work.

“Had this just been TU and the Forest Service, we couldn’t have gotten this done,” said Jeff Wright, TU’s Southern Appalachians project manager.

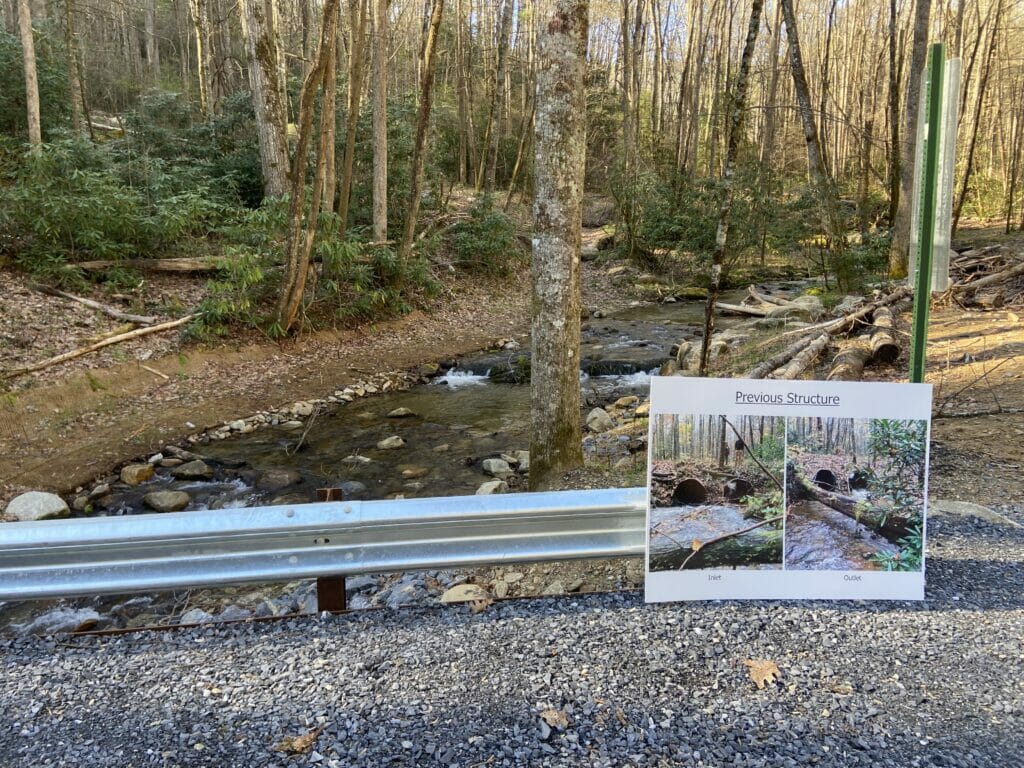

Both projects were rooted in the need to upgrade road crossings. In each case, culverts meant to pass stream flows under the gravel roads were too small to handle high water levels. That contributed to ongoing damage to the roads.

The culverts were also perched, meaning the downstream ends were above the stream level. That created small waterfalls that kept fish and other aquatic organisms from being able to move upstream.

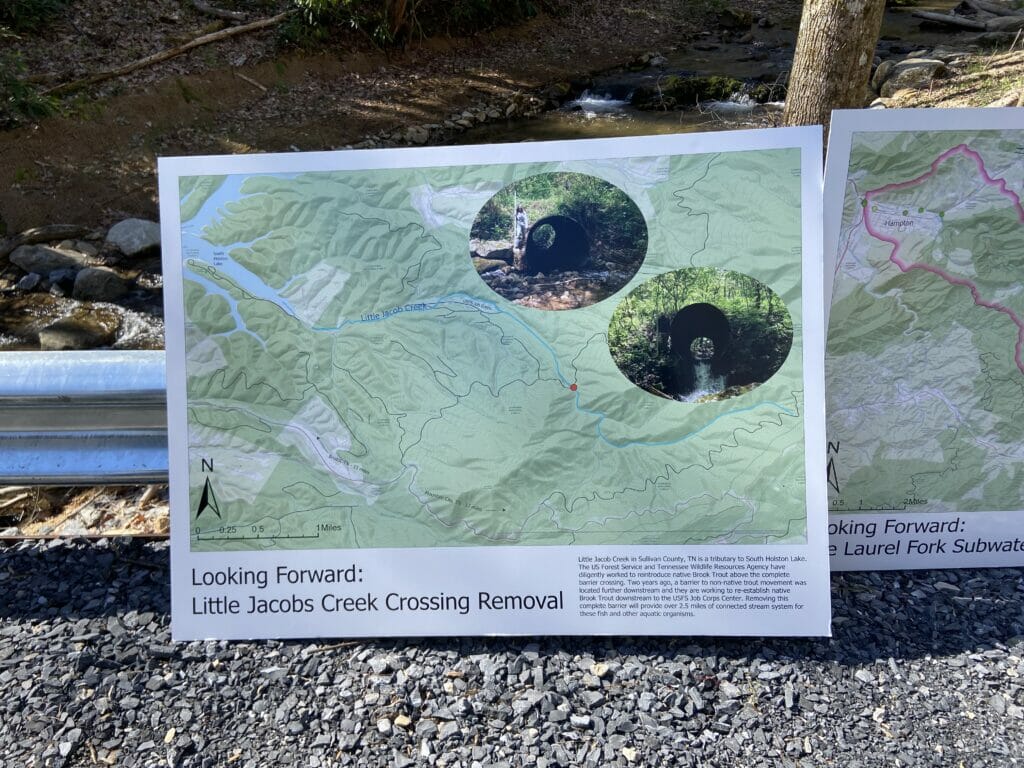

The two sites shared another special feature. Not far below the crossings, both creeks have waterfalls that serve as natural barriers. That made the creeks ideal candidates for the restoration to native brook trout-only streams.

A logistical challenge

Trout Unlimited and collaborators complete dozens of culvert replacement projects annually around the country. All are unique and offer their own set of challenges, but the Wolf Creek and Trail Fork jobs were definitely on the high end of the complexity scale.

It wasn’t so much the engineering of crossings that would meet traffic requirements while also being resilient to flooding. It also was a matter of getting the necessary materials to the sites, which were miles of sometimes steep and winding travel away from pavement.

When contractor Ed Wiley of Valley Resource Construction first looked at the challenge, he was not confident. The bridges were to be delivered in just a couple of pieces — three for the Wolf Creek and just two for the Trail Fork location.

“How could we do that?” Wiley asked, rhetorically.

The answer? Slowly.

The large bridge pieces, which were manufactured in Michigan, were staged in a field in Del Rio, a small community on the banks of the French Broad River. Hauling each of the massive pieces deep into the mountains required a day apiece. Once the pieces were on site, finishing the jobs wasn’t too bad.

The Wolf Creek bridge features a metal pan covered by gravel — a design suited for heavier travel. The bridge at Trail Fork is on a road used only for maintenance and not normally open to public travel, so it features a wooden slat surface. Both have estimated lifespans of roughly 50 years.

In addition to placing the spans over the water, crews also rebuilt the streambeds at the sites, placing rocks to mimic the creeks’ natural appearance and function above and below the restoration sites.

Now for the fish

Restoring native brook trout to the streams was no small challenge, either.

First, the streams had to be cleared of non-native rainbows that had taken over after long-ago stockings.

“Historically, rainbow trout were stocked so people had things to fish for,” said Petre, who is with the Tennessee Wildlife Resources Agency. “But that’s not what we want. Here in Tennessee, we want natives.”

Rather than using a piscicide such as rotenone, which kills all fish in a water body, the TWRA crews took a mechanical approach.

Over the course of several years, teams outfitted with backpack electroshocking equipment used the gear to collect all the rainbow trout in the streams above the waterfalls. Only after biologists were convinced that the streams were devoid of all rainbows did efforts to reintroduce brook trout take off.

Both streams were stocked with native brook trout from multiple source stocks. That included fish captured in other streams in the area, as well as fingerling brook trout raised from native-sourced eggs at the Tennessee Aquarium in Chattanooga.

“We did that because we looked at the genetics of the source stocks and some had unique genetic signatures that we wanted to keep,” Petre said. “Bringing multiple source stocks increases genetic diversity.”

Petre said she will be back in the watershed this summer with electrofishing gear to survey the trout populations in both streams.

And while those involved with the Wolf Creek and Trail Fork projects are rightly proud of the two new crossings, they also look forward to keeping the momentum going.

Surveys have identified many other road-stream crossings in the forest that will benefit from restoration. An increased emphasis on funding for that kind of important work, much of it made possible through the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law, will help ensure that TU and its collaborators will stay busy with challenging, rewarding, important work to improve the forest’s infrastructure and watershed health.

Project partners list for Wolf Creek & Trail Fork: